Summary

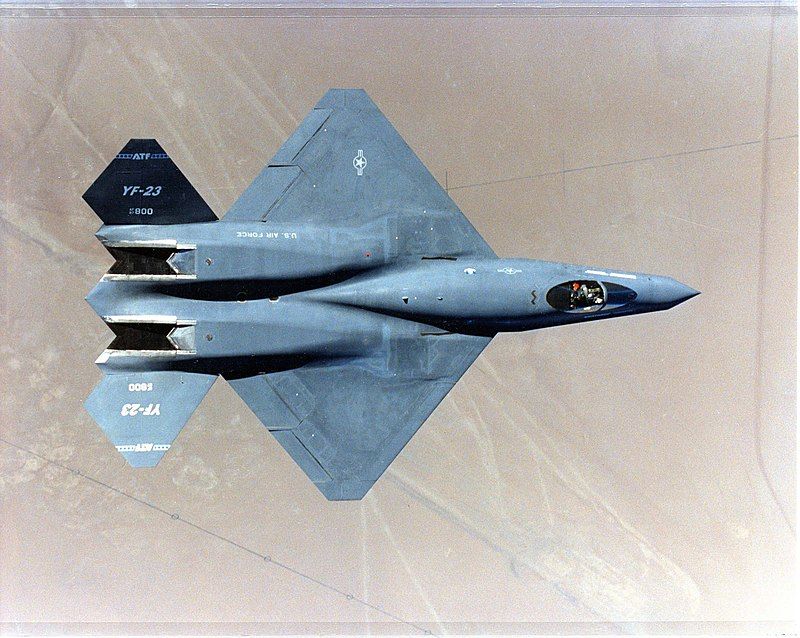

- The YF-23, designed by Northrop Grumman and McDonnell Douglas, was a contender in the United States Air Force’s Advanced Tactical Fighter (ATF) program in the 1980s.

- Two prototypes of each competing design (YF-22 and YF-23) were built for testing and evaluation.

- Many experts considered the YF-23 to be the better performer of the two. It had better supersonic cruise performance, better stealth, and only slightly less maneuverability than the YF-22 at extremely low airspeeds.

In the early 1990s, Brig. Gen. Chuck Yeager (one of my boyhood heroes) made TV adverts plugging the Northrop YF-23 “Advanced Tactical Fighter” (ATF). At the time, I thought that if an icon of Chuck Yeager’s stature plugged the YF-23, it was a surefire bet to win the US Department of Defense (DOD) contract. But that was not the case.

Related

The Various Achievements Of Legendary US Test Pilot Chuck Yeager

Seventy-five years ago, on October 14th, 1947, Charles (Chuck) Yeager became the first pilot in history to break the sound barrier.

Instead, the Lockheed YF-22 (now known as the Lockheed Martin F-22 Raptor) won that bid. Simple Flying now examines how Lockheed beat out Northrop for the US Air Force ATF contract, to the disappointment of Chuck Yeager and others.

Northrop merged with Grumman in 1994 to form Northrop Grumman. One year later, Lockheed merged with Martin Marietta to form Lockheed Martin.

The why and the wherefore of the ATF program

The ATF traces its roots back to 1981 when the program’s planners envisioned an air superiority fighter that would supersede the then-McDonnell Douglas F-15 Eagle and thus put the USAF in a better position to counter the emerging threats of the Soviet Union’s Sukhoi Su-27 “Flanker” and the Mikoyan MiG-29 “Fulcrum” fighters.

In November 1984, the USAF’s System Program Office (SPO) released its Advanced Tactical Fighter Statement of Operational Need (SON), followed by the System Operational Requirements Document (SORD) in December 1987.

Related

Why The YF-23 Black Widow Never Made It Into Service

The jet competed against what is now known as the F-22 Raptor

Several aerospace and defense companies had submitted proposals for the new aircraft programs between the SON and the SORD. By 1986, the USAF had narrowed the list down to two candidates: Lockheed (in conjunction with Boeing and General Dynamics) with the YF-22 and Northrop (in tandem with McDonnell Douglas) with the YF-23.

Two specimens of each competing design were built for testing and evaluation. The YF-23 was given the unofficial name of “Black Widow II,” partly in homage to the WWII-era P-61 Black Widow night fighter. Also, the first prototype briefly had a red hourglass painted on its ram air scoop to prevent injury to the ground crew, which resembled the telltale marking on the underside of the venomous black widow spider.

YF-22 vs. YF-23 head-to-head

From there, a four-year development & evaluation process commenced. By many experts’ accounts, the YF-23 was the better performer of the two, including better supersonic cruise performance, better stealth, and only slightly less maneuverability than the YF-22 at extremely low airspeeds. The “Black Widow II” also coaxed a better raw performance from its then-revolutionary General Electric (G.E.) variable-cycle YF120 engine.

Here is a head-to-head comparison of their specifications for perspective:

|

YF-22 |

YF-23 |

|

|

Fuselage Length: |

64 ft 6 in (19.65 m) |

67 ft 5 in (20.55 m) |

|

Wingspan: |

43 ft 0 in (13.1 m) |

43 ft 7 in (13.28 m) |

|

Height: |

17 ft 9 in (5.39 m) |

13 ft 11 in (4.24 m) |

|

Empty Weight: |

33,000 lb (14,970 kg) |

32,000 lb (14,515 kg) |

|

Gross Weight: |

62,000 lb (28,120 kg) takeoff |

64,000 lb (29,030 kg) takeoff, 51,320 lb (23,280 kg) combat weight |

|

Powerplant: |

2 × Pratt & Whitney YF119-PW-100 afterburning turbofans, 23,500 lbf (105 kN) thrust each dry, 30,000 or 35,000 lbf (130 or 160 kN) with afterburner |

2 × General Electric YF120 afterburning turbofan engines, 23,500 lbf (105 kN) thrust each dry, 30,000 or 35,000 lbf (130 or 160 kN) with afterburner |

|

Max Airspeed: |

Mach 2.2 (1,450 mph, 2,335 km/h) at altitude |

Mach 2.2 (1,450 mph, 2,335 km/h) at high altitude |

|

Supercruise: |

Mach 1.58 (1,040 mph, 1,680 km/h) at altitude (military power only) |

Mach 1.72 (1,135 mph, 1,827 km/h) at altitude |

|

Combat Range: |

800 mi (1,290 km, 696 nmi) |

651–695 nmi (750–800 mi, 1,210–1,290 km) |

|

Service Ceiling: |

65,000 ft (19,800 m) |

65,000 ft (20,000 m) |

|

Wing Loading: |

74.7 lb/sq ft (365 kg/m2) |

67.4 lb/sq ft (329 kg/m2) (54 lb/sq ft at combat weight) |

|

Thrust/Weight: |

1.13 |

1.09 (1.36 at combat weight) |

|

Maximum g-load: |

+7.9 g (highest tested) |

+7.1 g (highest tested) |

Yet, in spite of the YF-23’s many advantages, the YF-22 won the contract on April 23, 1991, and became the F-22 Raptor. The rest is history.

Why the YF-22 won/Why the YF-23 lost

Bottom Line Up Front (BLUF, to use a common military acronym), according to an April 2018 article in The National Interest penned by then-Defense Editor Dave Majumdar:

“While in many ways, Northrop’s losing YF-23 was a much better design, but the U.S. Air Force chose the Lockheed aircraft because it believed that company would better manage the development program—and because the service thought the Raptor would cost less.

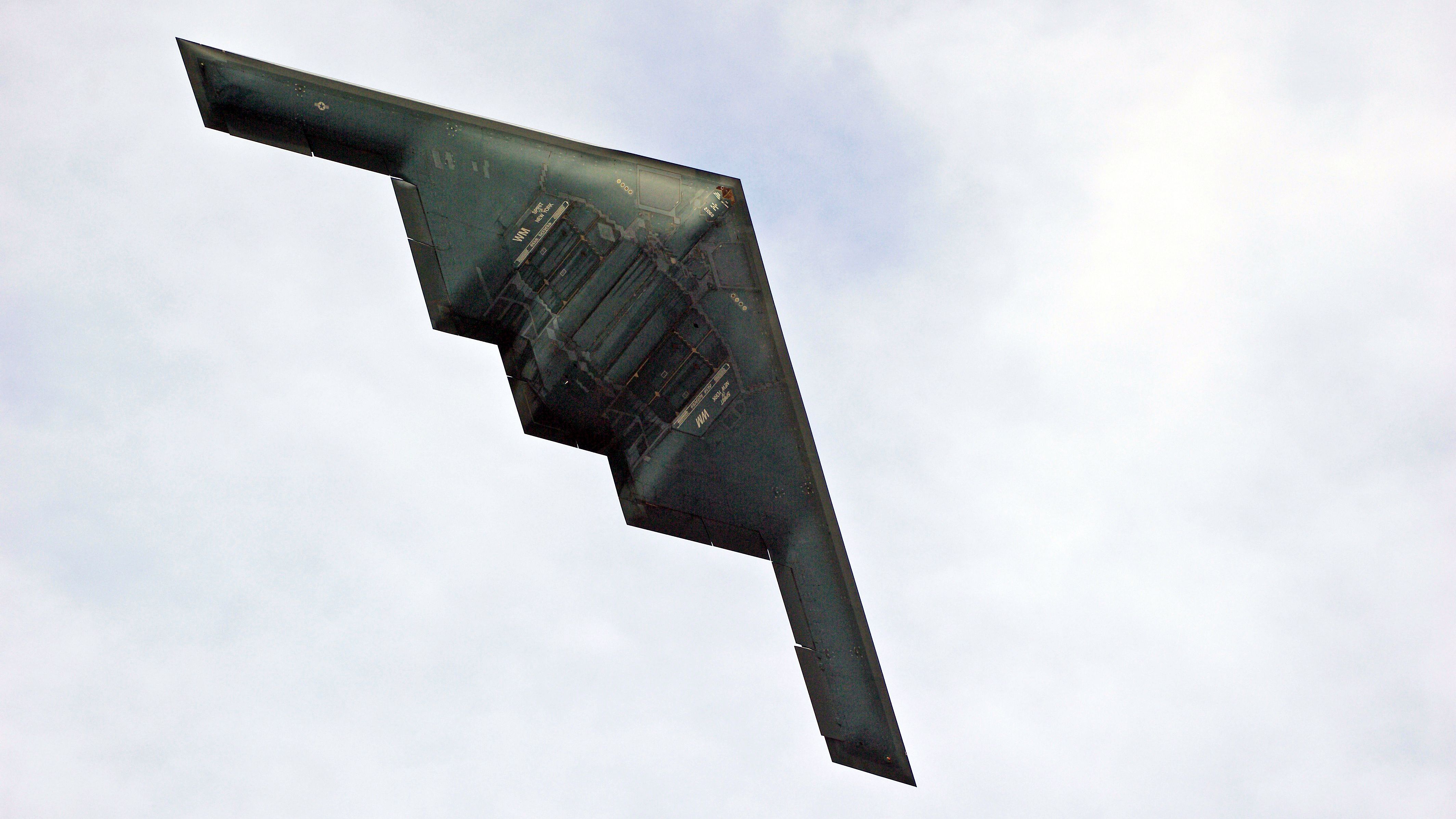

“At the time, Northrop was in the doghouse with the Pentagon and the U.S. Congress because of massive cost overruns on the B-2 Spirit stealth bomber and several other projects. Meanwhile, partner McDonnell Douglas wasn’t faring much better.”

Related

3 Reasons Why The US Has Never Sold Its F-22 Raptor Fighter Jets To Allies

The US would rather keep the stealth technology close to home.

We know now that the B-2 Spirit “Stealth Bomber” eventually succeeded, despite the media and congressional controversy that its massive price tag generated back in the late 1980s and early 1990s. But by that time, the resurrection of Northrop Grumman’s reputation came too late to save the YF-23.

Photo: Philip Pilosian | Shutterstock

There was also the angle of attack (AoA) factor to consider. To quote Mr. Majumdar again:

“‘ACC [Air Combat Command] pilots were enamored with dogfighting and Lockheed gave a good visual demonstration of high AOA—albeit a very limited and benign test,’ the source said. ‘Northrop chose not to do high AOA during DemVal and that was a mistake. Both airplanes could do the same exact maneuver—trimmed, high AOA. As it was, the YF-22 “appeared better” because they did something visually exciting and Northrop couldn’t—or so it was inferred.’”

“Perception is reality,” as the saying goes. Of course, there’s also the intangible that the YF-22 came from Lockheed’s legendary and superbly reputable “Skunk Works” program, the brainchild of the late great Clarence “Kelly” Johnson.

YF-23 Postscript: Resurrected by Japan? Where Are They Now?

Unsurprisingly, to this day, many military aviation pundits who favored the YF-23 over the YF-22 still wonder what might have been. Well, some aviation reporters have floated the possibility that the Japan Air Self-Defense Force (航空自衛隊/Kōkū Jieitai) (JASDF; 空自/Kūji) may yet resurrect the project, though that is mostly speculation at the moment. The embedded YouTube video tells the story:

In case any of our readers are wondering about the fate of the original YF-23 airframes, the good news is that both aircraft were preserved for posterity as museum static displays:

- YF-23A PAV-1, USAF Serial No. 87-0800, “Gray Ghost” Registration No. N231YF, on display in the Research and Development hangar of the National Museum of the United States Air Force at Wright-Patterson AFB, Ohio (near Dayton).

- YF-23A PAV-2, USAF Serial No. 87-0801, “Spider”, Reg. No. N232YF, at the Western Museum of Flight at Torrance Airport’s Zamperini Field (named for famed WWII hero and former USC track & field star Louie Zamperini) in Torrance, California.