The first step in the incredibly complex process of transporting passengers by air from an origin to a destination is the composition of a flight plan. The flight plan is a lengthy legal and informational document that contains much more than just the routing for the flight. Flight plans are assembled by highly trained and licensed dispatchers who make the plan available to pilots anywhere from 90 minutes to an hour before departure. Flight plans are the framework for every commercial airline departure, and this article will identify some of the critical elements of a flight plan and talk about what is contained in each one.

Header and release

How a flight plan is organized depends on how the airline has formatted its flight planning software. While many differences exist from company to company, the first part of any flight plan usually shares commonalities.

Primarily, the flight number, the origin and destination, the aircraft registration, the flight time, and the pilots are almost always listed near the beginning of the flight plan. These items are some of the most important, so they appear at the front of the plan. For example, one of the first things pilots should do when they arrive on the flight deck is to ensure the plane’s tail number listed on the flight plan is the same plane they are sitting on. Believe it or not, flights sometimes depart using the wrong plane if there is a communication mix-up about which gate the plane was parked at.

The “release” is usually collocated on the front of the flight plan. Flight plans are often colloquially referred to as releases, and this is because the pilots are required to “sign the release” section of the flight plan before pushing back from the gate. This signature, particularly the captain’s, is a legal acknowledgment that the pilots accept the flight plan as filed.

Pilots wait to sign the release section of the flight plan if there is a disagreement about the amount of fuel or maintenance status of the plane until the issue has been sorted out. Signing the release not only indicates an acceptance of the plane and the flight plan but also indicates that the pilots are adequately rested and are mentally and physically fit to fly the sector.

Flight information and navigation log

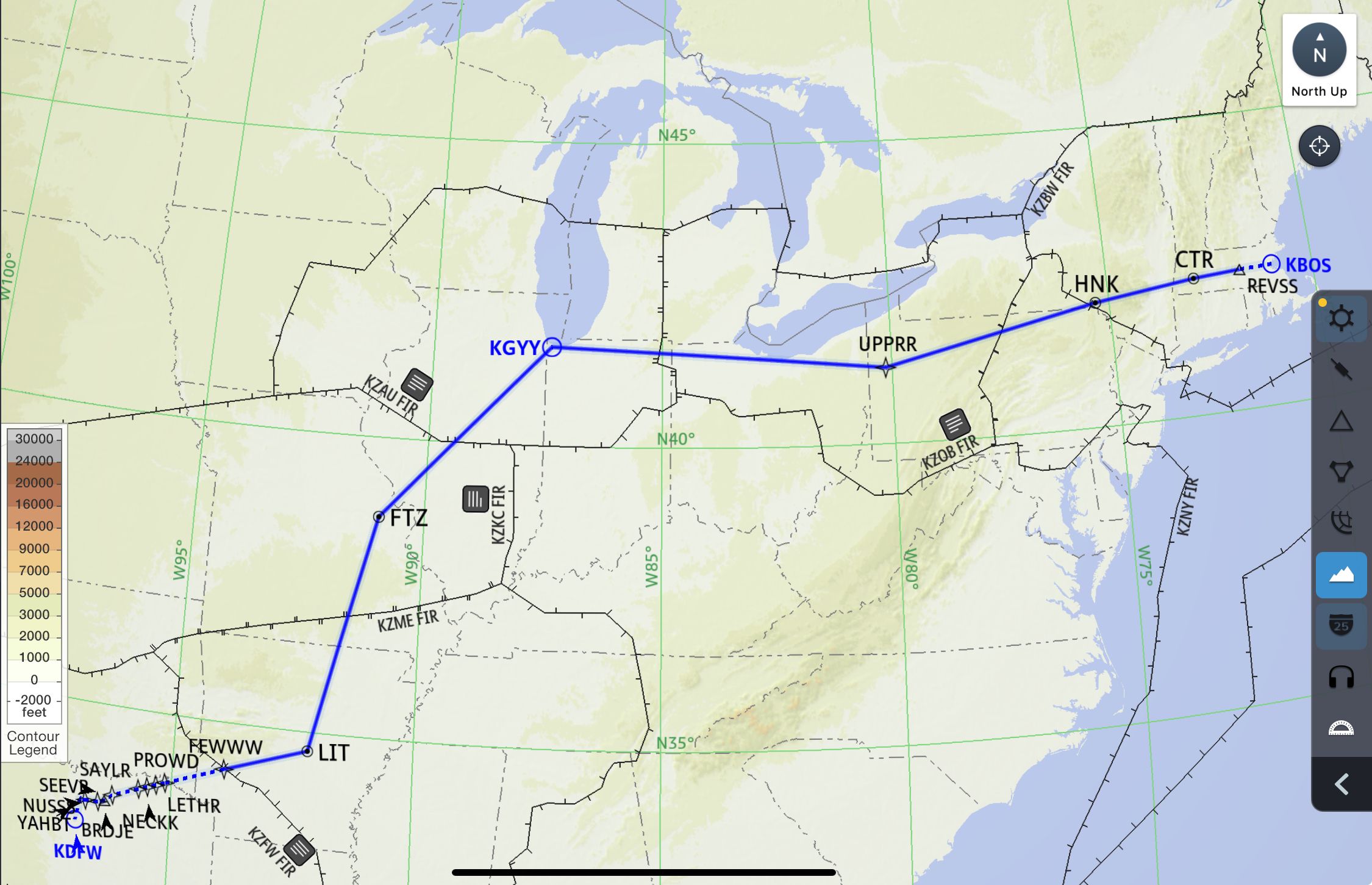

Flight plans detail the routing that the pilots will follow. The waypoints and airways the dispatcher selected for the flight’s navigation are contained in the nav log section of the flight plan. Dispatchers put the navigation log together using information provided by the company, flight planning software, and air traffic control (for instance, ATC might have “preferred routing” for particular airspace sectors).

The compilation of this navigation data is sent to the pilots in the flight plan and ATC so that they can either approve the plan or amend it as necessary. Any change that ATC needs to make to the plan is sent to the pilots via the route clearance and the terminal departure and arrival procedures they will use.

Photo: Omar Memon | Simple Flying

The nav log contains each waypoint name, the estimated time of arrival at the waypoint (assuming the flight departs on schedule), the distance to the next point, the altitude and winds aloft, the time remaining (both to the next waypoint and for the remainder of the flight), and, notably, the planned fuel.

Traditionally, flight plans are printed on paper. Pilots fill in the actual time over waypoints and the fuel remaining (which shouldn’t be far off from the plan without good reason) and use this to track their progress. At many airlines, flight plans are interacted with digitally on pilots’ EFBs. They fill out the time and fuel, and the electronic flight plan will display their values against the plan without the pilots having to do the simple mental math. The fuel and time are also sent to the dispatcher in real-time so they know how the flight is progressing relative to what they or their colleagues planned for.

Fuel, payload, and cargo

Most flight plans contain a dedicated section identifying the fuel, planned passenger count, and cargo. This section distinguishes the difference between the plane’s zero fuel weight (the plane’s basic empty weight, passengers, and cargo) and the ramp weight (what the plane will weigh after the fuel is uploaded). As such, block fuel, taxi out fuel, minimum takeoff fuel, trip fuel, alternate fuel, reserve fuel, and landing fuel are all presented as variables. This helps pilots quickly identify what is needed to be safe and legal. Minimum takeoff fuel and reserve fuel are non-negotiable values (legal), while the planned landing fuel and discretionary fuel can be adjusted for what the pilots feel is safe and prudent.

Below is a table generally representing a 670 nautical mile Airbus 321 flight plan at 35,000 feet. You’ll notice that values can be deduced from known variables. For example, the landing weight equals the takeoff weight minus the en route burn. Likewise, the landing fuel is equal to the block fuel minus taxi and en route fuel burn. All these figures are presented so that pilots can quickly and easily reference the values.

|

Passengers |

190 |

|

Payload |

5,000 |

|

Zero Fuel Weight |

154,300 |

|

Ramp Weight |

174,300 |

|

Block Fuel |

20,000 |

|

Taxi |

350 |

|

Min. Takeoff |

17,500 |

|

Takeoff Weight |

173,950 |

|

Enroute Burn |

12,050 |

|

Reserve Fuel |

4750 |

|

Landing Weight |

161,900 |

|

Landing Fuel |

7,600 |

One thing that every flight plan has in common is that the planned landing fuel is always greater than the reserve fuel. Dispatchers and pilots prefer a cushion between these values to ensure the legality and safety of the flight in case unexpected weather, delays, routing, or any other additional fuel burn are incurred along the way.

Dispatcher remarks and MELs

Yet another section of the flight plan is dedicated to notes from the dispatcher and the known and acceptable inoperative items on the plane. The dispatcher might leave remarks about temporary flight restrictions, closed airspace, anticipated turbulence, justification for certain altitudes, single-engine driftdown fuel considerations, and VIP movement at the departure or arrival airport. So much can be added in this section; it’s entirely at the dispatcher’s discretion to add items they want the pilots to know about.

An important note that dispatchers will infrequently add is that the flight crew should not accept flight plan deviations or “shortcuts” from ATC. Sometimes, a flight’s navigational path is planned in a way that seems illogically long or circuitous (see the flight plan below from Boston to Dallas). There’s always a reason for this, sometimes to avoid the worst headwinds. If the pilots took a shortcut from ATC that exposed them to these headwinds, the flight plan would become less valid since fuel planning did not consider the reduced ground speed. When dispatchers plan in this way, they usually leave a note about it.

Photo: Jeppesen

MEL is the abbreviation for a plane’s minimum equipment list. The MEL is an exhaustive list of components and systems legally allowed to be inoperative so long as the associated procedures are complied with. For example, a broken seatbelt on a passenger chair would render that seat unusable, and the seat would have to be placarded accordingly. A small note would also have to be placed somewhere in the flight deck and the plane’s technical logbook.

All of the MELs for a plane must be listed on the flight plan until the component is fixed. This gives the pilots a reference from which to identify the inoperative parts of their aircraft so they can reference their procedures, actions (if required), and considerations. If the pilots discover something during their preflight that requires it to be added as an open write-up, the dispatcher needs to send an amended release with the MEL number added to the flight plan. This is one of the biggest steps to ensure that airlines legally operate airworthy aircraft.

NOTAMs

NOTAMs, or “notices to air missions,” are contained in a dedicated part of the flight plan that usually spans many pages. The dispatcher must add all of the NOTAMs that are relevant to a flight, which includes the origin, destination, and alternate airports. NOTAMs also cover all the airspace en route, which is why they take up so much space on the flight plan. Using the example from above, Dallas-Ft. Worth International alone had 88 individual NOTAMs at the time of writing this article. Boston had an additional 57. The addition of en route NOTAMs usually takes a cross-country flight plan into the mid-hundreds of NOTAMs, which is many thousands of words.

Related

Why Printed Paperwork Still Plays An Important Role For Today’s Pilots

An age-old method for modern aviation.

The advent of digital flight plans and electronic flight bags aids pilots. Many airlines have ways for their pilots to filter NOTAMs based on specific runways or arrivals and departures, which makes it much easier to identify the most relevant notices. In signing the flight plan, pilots acknowledge that they have reviewed all pertinent NOTAMs about their flight, and this task is made much easier with the help of a bit of technology.

Weather

The last section to discuss for this article is the weather section of the flight plan. Weather is important for many reasons, and its inclusion in the flight plan comes back (once again) to legalities. Specifically, the need for an alternate is predicated on the weather at the destination from an hour before to an hour after for domestic flights. Strong crosswinds or low visibility require dispatchers to add an alternate (or sometimes two) if conditions warrant. The means to determine this are the METARs and, more generally, the TAFs (or terminal aerodrome forecast) for the planned arrival time.

Dispatchers inform the pilots of the weather they use to plan the flight so that everyone involved can be sure that all the bases are being covered. At the airlines, the dispatching of a flight is a shared responsibility between the pilots and the dispatcher, which is why it’s so essential for this information to be made available to the relevant parties. Everyone checks each other’s work to ensure safety and compliance with the regulations. This is why other items, like NOTAMs and MELs, are included in the flight plan.

Plan the flight, fly the plan

Flight plans are highly accurate and meticulously planned. A solid flight plan (all but guaranteed at the airline level, thanks to the skill of dispatchers) is the bedrock for a safe flight. It’s incredible how much fidelity a flight plan document shares with the actual flight it has charted, assuming the pilots can execute the plan as anticipated. Fuel and time are nearly spot-on, a testament to the accuracy of man, machine, and technology.

Photo: Ryan Patterson I San Francisco International Airport

That being said, flights are rarely ever flown exactly as planned. Taxi times diverge from what’s anticipated, weather pops up over the mountains, different altitudes are flown to avoid turbulence, or speeds are assigned to pilots for traffic management. In this way, a well-constructed flight plan won’t perfectly match the reality of the journey, but it will have done more than enough to give the pilots what they need to get the job done.