Summary

- The Curtiss-Wright C-76 Caravan was a WWII transport aircraft made of wood.

- Over 142,000 components for WWII were built by the Curtiss-Wright Corporation.

- The Baldwin Piano company became a contractor for Curtiss-Wright

Despite the horrors of war, World War ll saw many inventions that showed the good things humanity can do. In a previous article on Simple Flying about legendary aircraft, some of them were included not because they saw battle but because they contributed to the world’s knowledge about aircraft design, fabrication, and overall

Engineering

excellence.

5 Legendary Axis Fighter Planes Of WWII

Aircraft that changed the name of the game with advancements that go beyond the war and change history forever.

However, an idea that looks great on paper could prove to be a failure in real life. Such is the story of the Curtiss-Wright C-76 Caravan.

The Curtiss-Wright C-76 Caravan was a military transport aircraft intended for use by the United States Army Air Forces during World War ll.

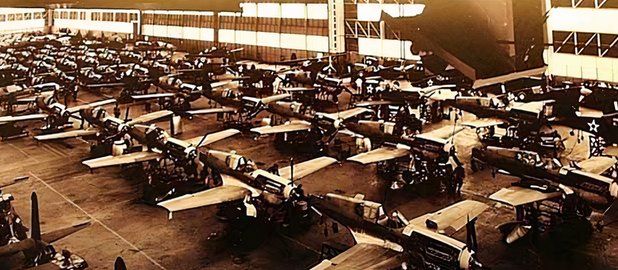

The Curtiss-Wright Corporation was created on July 5th, 1929, through a merger between 12 companies. The company became the country’s largest aviation firm, building a whopping 142,000 engines and other components during the Second World War.

The C-76’s first flight was on May 3rd, 1943. It was made entirely of wood because the possibility of a metal shortage was a real concern at the time. The National WWll Museum in New Orleans says, “As the United States accelerated production of everything from planes and ships to tanks and artillery shells after it entered the war in December 1941, the nation faced critical shortages of copper, zinc, and tin.”

With that said, in 1941, the Curtiss-Wright Corporation was contracted by the United States Army Air Force to create, design, test, and build an all-wooden ship that could meet or exceed the expectations set forth by the

U.S. army.

|

General Characteristics |

C-76 Specs |

|---|---|

|

Crew: |

3 |

|

Capacity: |

45 troops max |

|

Length: |

68 ft 4 in (20.83 m) |

|

Wingspan: |

108 ft 2 in (32.97 m) |

|

Height: |

27 ft 3 in (8.31 m) |

|

Wing Area: |

1,560 sq ft (145 m2) |

|

Gross Weight: |

28,000 lb (12,701 kg) |

|

Engines: |

2 × Pratt & Whitney R-1830 Twin Wasp |

|

Propellers: |

3-bladed |

Source: Bowers, Peter M. (1979). Curtiss aircraft, 1907-1947. (pg. 471–473)

The strength of wood

The C-76 was designed by Curtiss-Wright’s chief designer, George A. Page, Jr. The National Air and Space Museum says he was “an Early Bird and a pioneer aircraft designer.” His design featured a high wing and two engines with the necessary thrust for takeoff and landing.

The C-76 cargo transport aircraft was designed using plywood. Numerous types of wood were considered, including balsa and birch, before the designers chose mahogany because of its durability.

Even decades later, the US military’s specification for aircraft-grade plywood included “imported African mahogany or American birch veneers laminated in a hotpress using waterproof glues” with a core of poplar or basswood, per the Experimental Aircraft Association (EAA).

Plane the Piano

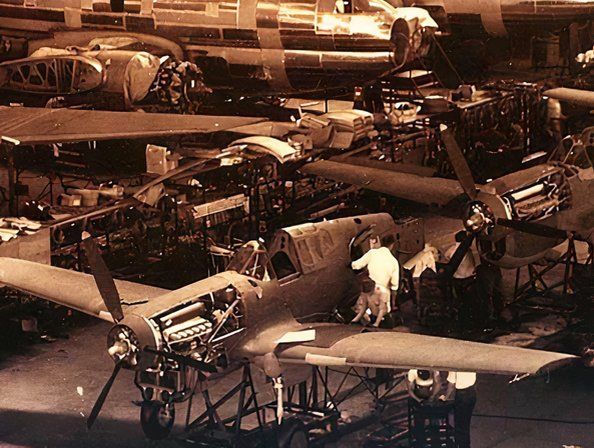

Because Curtis-Wright requested more wood, various furniture companies were subcontracted for the project. One of these companies was the Baldwin Piano Company.

According to baldwinpiano.com, “Baldwin[‘s] business was interrupted in 1942 when the U.S. War Production Board ordered all piano building stopped due to the war effort. Because of its [wood]working expertise, Baldwin manufactured wings, fuselage parts and center sections for the Aeronca PT-23 training plane and the Curtiss-Wright C-76 cargo plane, as well as parts for fighter, bomber and glider aircraft.”

One of the very interesting things about this is that the 41-ply maple used in Baldwin pianos after the war was partly the result of lessons Baldwin had learned from constructing aircraft wings.

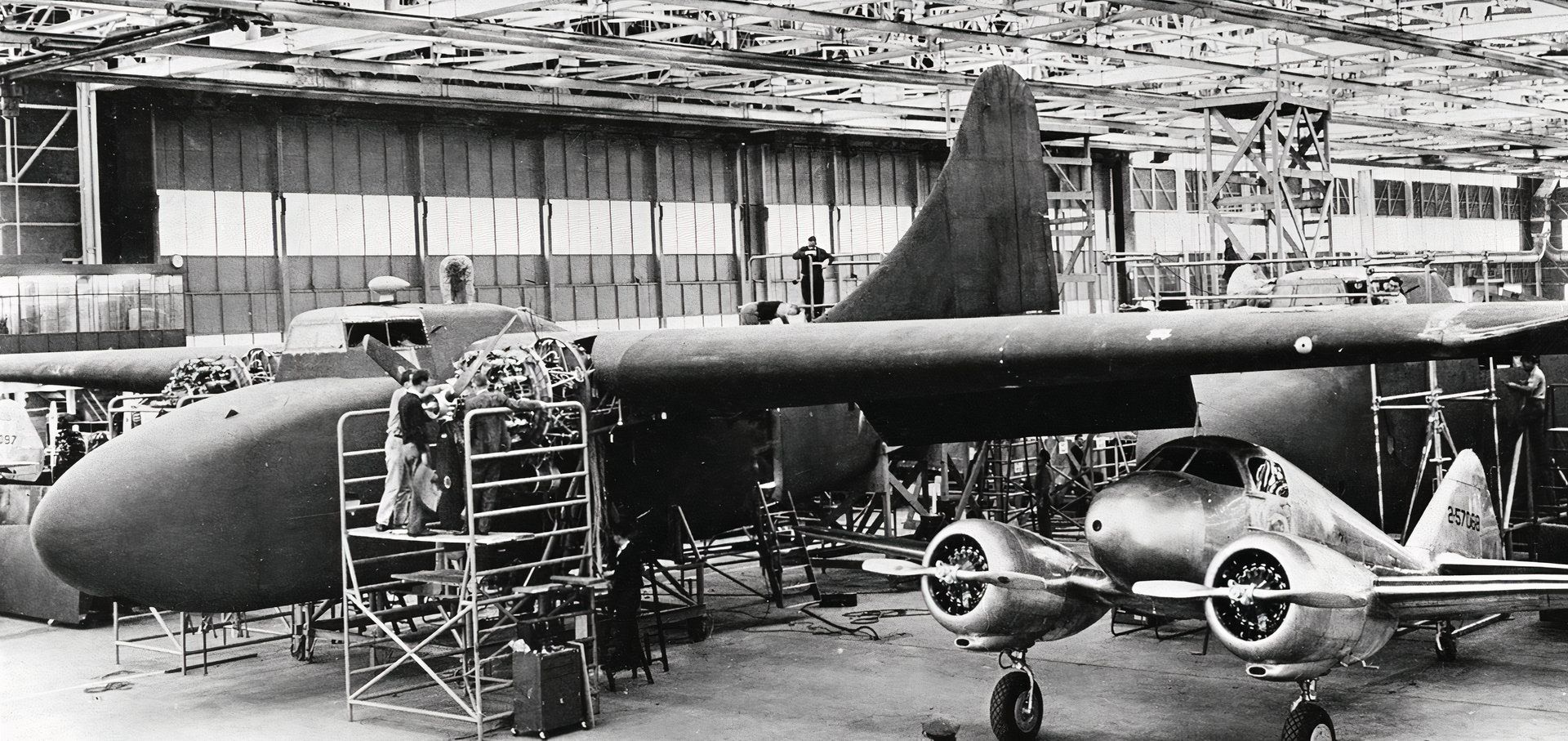

Variants and plant locations

Curtiss-Wright had two plants used for these planes during production. One was in St. Louis, Missouri, and the other was in Louisville, Kentucky. Additional plants were located throughout the continental United States and produced other types of aircraft, such as the P-40 fighter, which was produced in Buffalo, New York.

|

Variants |

Prototype or Prod |

# Built |

|---|---|---|

|

YC-76 |

Prototype |

11 built |

|

C-76 |

Production |

5 built |

|

C-76A |

Production |

Had ordered, none built |

|

YC-76A |

Production |

9 built |

Source: Andrade, John (1979), p. 80. U.S. Military Aircraft Designations and Serials since 1909. Midland Counties Publications. ISBN 0-904597-22-9

Even with additional variants built upon improvements from the previous versions, the aircraft still had many challenges. For one, the aircraft was extremely heavy, and secondly, the aircraft’s 2nd flight ended in disaster when it broke apart midair, and the pilots were presumed dead.

“The first flight [of the C-76] was made and the airplane was very heavy. It developed some serious vibrations. In fact, the pilot was awful glad to make a quick circuit to get back on the ground … two of the Curtiss test pilots took it out on a flight and the Army requested that our project officer on the airplane be allowed to fly along on this trip. The Curtiss Company refused. We were very glad that they refused because on this second flight, [the C-76] flew apart and the pilots were lost and so was the plane.” – Colonel J.W. Sessums, Design and Engineering Problems of Aircraft Production

This shows just how hard it was and still is to create something new and try to get it to work. The idea was wonderful on paper because there was a problem – a possible metal shortage, and a solution – making a plane out of common materials such as wood.

However, the cons significantly outweighed the pros in this case. Although wood was more sustainable, it was also heavier and more costly. The engines struggled under the extra weight, and the C-76 failed multiple critical flight tests as a result.

After Curtiss-Wright’s design and test campaign, US metals were still being produced at a high enough rate that there was very minimal risk of a shortage. Ultimately, aluminum was selected as the go-to metal for warplanes going forward, and the Curtiss-Wright C-76 Caravan found its place in history as an interesting experiment.