As the gateway to one of the world’s premier cities, New York’s John F. Kennedy International Airport is an airport that most frequent fliers and pilots visit many times over a lifetime of traveling. Commonly known as JFK, the airport opened in the post-World War II era in 1948 as “Idlewild Airport.” In the 76 years since its opening, the airport ushered in the era of jet travel, featured cutting-edge terminal and airport designs, and has been renamed. This article is dedicated to the operational experience of pilots at New York’s John F. Kennedy International Airport.

Idlewild

Let’s first touch on the name Idlewild, JFK’s original name. Idlewild Golf Club was the original occupant of the land in the Jamaica, Queens borough of New York before JFK was constructed. New York City officials went back and forth about the airport’s name before its opening and settled on Idlewild Airport in homage to the Golf Club.

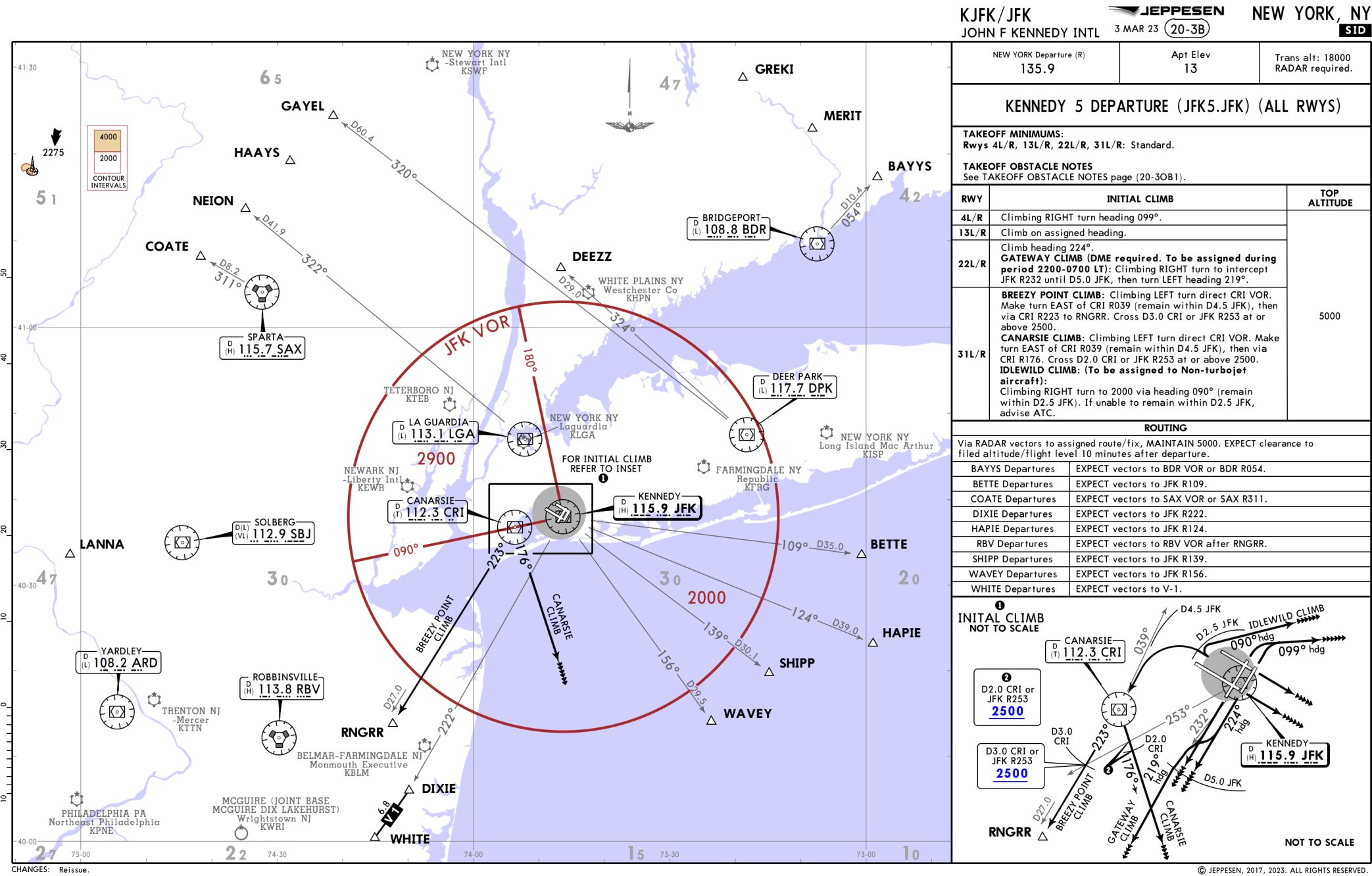

Fifteen years later, the airport was renamed after the late President John F. Kennedy following his assassination in 1963. Though the name Idlewild has long since been removed from the airport’s official moniker, the “Kennedy 5 Departure” features the “Idlewild climb” for non-jet traffic departing runways 31L/R. After takeoff, the Idlewild climb turns piston planes just north of the airport onto a westerly heading while climbing to 2,000 feet.

Departure procedures

While we’re on the topic of departures, JFK is rather unique in its philosophy for clearing departing traffic from the immediate airspace. JFK is different from many other large airports because of the lack of available departures for ATC to assign pilots.

Compared to places like Dallas, Miami, or Phoenix, New York operates more similarly to Chicago O’Hare and only has three available departure procedures (those of you who read the previous article about O’Hare might recall it only has one departure, the O’Hare 8).

Photo: Jeppessen

ATC can assign the DEEZZ 5, Kennedy 5, or SKORR 5 departures depending on the runways in use and direction of the departing plane. These procedures feature either an immediate turn or radar vectors compared to the straight-out departures that so many other airports have.

These procedures aim to get planes turned away from LaGuardia’s and Newark Liberty’s departure and arrival corridors as quickly as possible. Departure ATC often gives radar vectors for the first few turns before clearing pilots directly to a waypoint on the procedure that correlates to the flight’s route progression.

The bottom line is that flying out of JFK usually comes with an immediate turn unless the airport is departing runways 22L/R and the flight’s destination is somewhere down the southeast coast of the US.

Arrivals

Like planes flying away from the city, arrivals also require de-confliction from the other airports in the busy New York airspace. Approaching runways 4L/R, 22L/R, and 31L/R is somewhat straightforward.

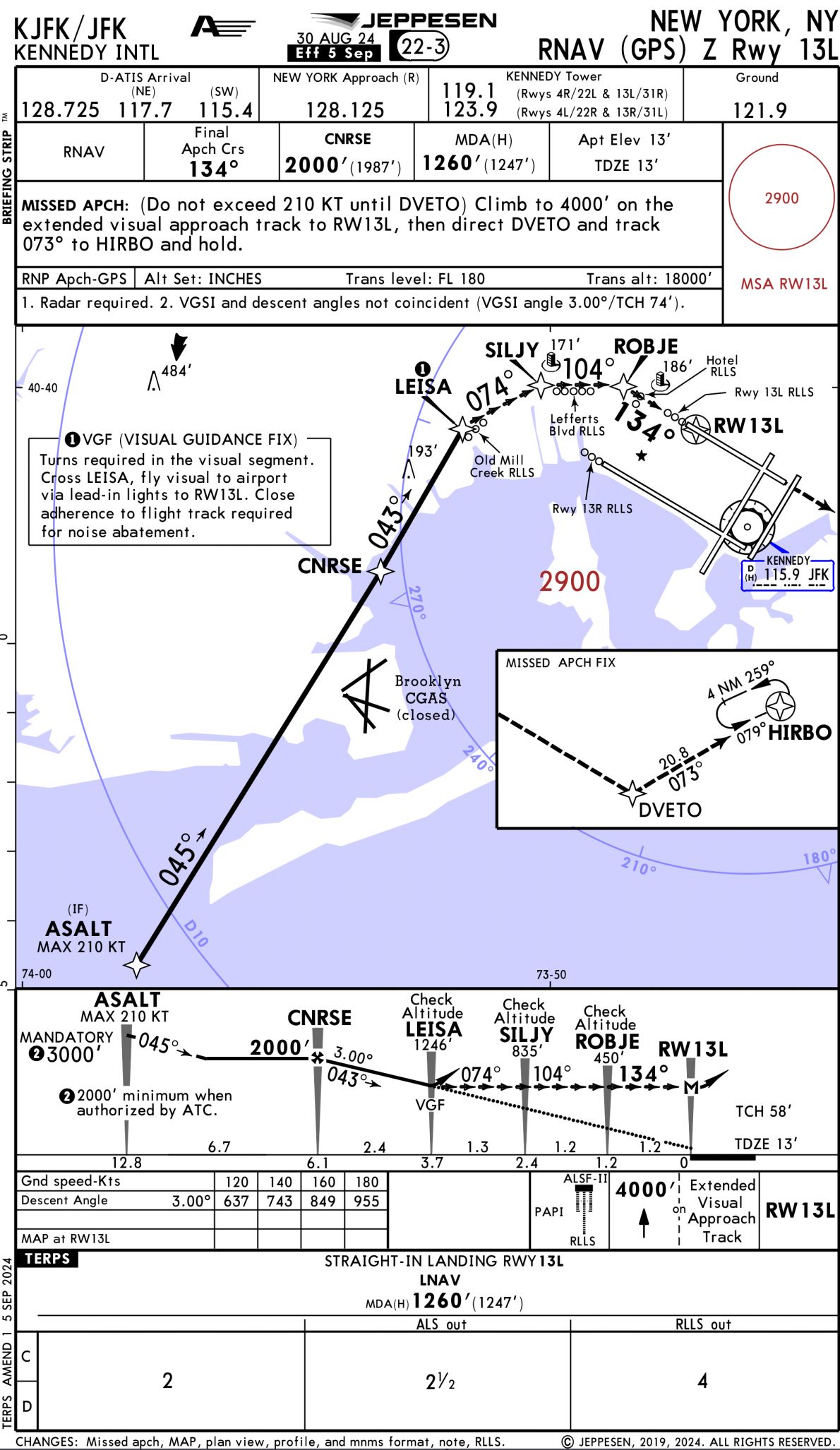

All of these runways have straight-in instrument approaches to them (though runway 22R’s ILS is offset to the right of the runway axis by 3 degrees for separation from parallel approaches). On the other hand, landing on runways 13L/R features a very late turn to final, rivaled only by the late turn on the River Visual to runway 19 at Reagan Airport in Washington, DC.

Runways 13L/R have conventional ILS and RNAV (GPS) approaches that require pilots to overfly Breezy Point and Canarsie on a northerly heading before making a late 90-degree right turn to align with the runway.

The approaches with the latest turns to final are the RNAV RNP to either 13L/R. These procedures feature a turn that rolls out on a 200-foot-high final approach. Both runways also have RNP Z approaches, which align planes with the runway well inside a two-mile final.

These approaches use “visual guidance fixes,” which are charted on the procedures. For example, pilots must turn over Old Mill Creek, Lefferts Blvd, and the “Hotel” on approach to 13L. These visual points are affixed with runway lead-in light systems to make them stand out. See the approach plate below for more details.

Photo: Jeppessen

Taxiing

Taxiing around JFK can be a mixed bag. Sometimes, you find yourself at the departure runway five minutes after leaving the gate, while other times, it takes upwards of 30 minutes to be number one for takeoff. JFK operates similarly to San Francisco, using intersecting runways for arriving and departing traffic simultaneously when wind conditions permit. Calm or light winds might allow arrivals to use runways 31L/R and departures from 22L/R.

The longest taxi times occur when the winds are stronger and ATC needs to dedicate one runway for arrivals and one for departures. It’s common for the wind to blow from the northeast, necessitating all operations to be on 4L/R. Landing traffic will use 4R, while departures will go off the inboard 4L.

Depending on how busy the airport is, controllers can stack a lot of arrivals on the taxiways to hold short of 4L after landing while they clear departures. This can lead to wait times of 10 minutes to cross the runway.

Controllers can also use non-operational runways as taxiways. When runways 4L/R are being used, a line of departures might form on 13R/31L if controllers need to sequence up 20+ planes on the ground simultaneously. This allows pilots to slip out of line to return to the gate or take off sooner to meet duty time limits.

New York, New York!

As Frank Sinatra sings in New York, New York, if you can make it here, you can make it anywhere. I suppose this is true of the piloting experience at JFK as well. The place can be calm and easily negotiated but can just as easily (and seemingly more frequently) be totally packed with planes and pilots from around the world.

Controllers expect pilots to know the operation at Kennedy well and be ready to respond quickly and accurately to instructions and inquiries. JFK is a fun airport to fly into and out of, and it features excellent views of one of the world’s best skylines on clear days. Such is the experience in “old New York.” Cue Frank Sinatra.