Summary

- The jet age began with four-engine aircraft, such as the de Havilland Comet, which allowed for non-stop transatlantic flights and paved the way for quadjet flying.

- Other manufacturers, like Boeing, Douglas, Vickers, and Illyushin, joined the quadjet market and developed their own four-engine aircraft with improved efficiency.

- However, the challenges of four-engine aircraft, such as structural issues and declining demand, led to the development of twin-engine jets like the Boeing 727 and McDonnell Douglas DC-9, and ultimately the decline of quadjets.

The jet age began with four-engine aircraft, and they ushered in new possibilities for aviation. Although two (and three) engine jets followed soon, quads retained a key role thanks to both their range and capacity. This is coming to an end now, with more improvements in twin-engine efficiency and declining demand for the largest aircraft. We take a look at the story of quadjets and all they have achieved.

The start of the jet age – four engines

Designing the de Havilland Comet

The earliest commercial jet aircraft was the de Havilland Comet. This first flew in 1949 and entered service with launch customer BOAC in 1952. The motivation for its development came very much from the desire for non-stop transatlantic flights between key cities. Transatlantic flights with piston-engined aircraft required stops en route. Pan Am’s Douglas DC-4 service between London and New York in 1946, for example, took over 17 hours, with several refueling stops.

Jet engines had been introduced for military use during the Second World War but were considered too expensive and inefficient for commercial aircraft. It was very much due to the perseverance of Geoffrey de Havilland that engines were developed for commercial use.

Other manufacturers were still sticking with piston engines. And although jet engines were successfully developed, these early engines were much less efficient than later ones. It was not until the development of high-bypass turbofan engines that efficiency really improved.

Photo: dvlcom | Shutterstock.

Quadjets from Boeing, Douglas, Vickers, and Illyushin

The Comet marked a major aviation milestone, allowing longer (and direct transatlantic) flights and a quieter, comfortable, pressurized cabin. This was the start of quadjet flying, but it soon ran into problems. It suffered from structural issues that lead to some catastrophic disasters, from which the Comet series never really recovered (although the issues were resolved by the later Comet models).

This may have been bad for de Havilland, but it had proven the possibilities of quadjets. Other manufacturers soon moved into the four-engine market, having learned from the problems the Comet faced. Other early quadjets that followed include:

- Boeing launched the Boeing 707 in October 1958 with Pan American World Airways (Pan Am).

- Douglas introduced the DC-8 the next year. It entered service in September 1959, with both United Airlines and Delta Air Lines.

- The British-made Vickers VC-10 (pictured below) was launched in April 1964 with BOAC. Only 54 aircraft were delivered, with only a few operating airlines in the UK, Middle East, and Africa.

- Illyushin Il-62. This Russian quadjet entered service in 1967 with Aeroflot. 292 were built, right up to 1995.

The Boeing 707 and Douglas DC-8

With the problems faced by the Comet, the Douglas DC-8 and the Boeing 707 were the jets that sold well and really brought the jet age to the masses. The 707 is often credited as the real start of the jet age, although it could be argued the DC-8 was just as significant technically.

Each aircraft had several variants, but the two most popular later types (the 707-320B and the DC-8-62) were very closely matched in size, speed, range, and passenger capacity. The 707 edged slightly ahead for range (9,913 kilometers against 9,641 kilometers) and speed.

Both manufacturers attracted plenty of customers, with several airlines, including Pan Am, Air France, and Lufthansa operating both types. Boeing got somewhat ahead, though, with its more committed adaption to customer needs.

It offered custom variants for several airlines, such as a longer-range model for Qantas and larger engines for Braniff to use on South American high-altitude routes. And the Boeing 720 proved a popular, shorter version capable of operating at smaller airports.

Ultimately, the 707 proved to be the most popular. Boeing went on to sell 1,010 707s (including all variants). Douglas sold 556 DC-8s. It established Boeing as a dominant civilian manufacturer.

Reducing the number of engines

The challenges with four-engine aircraft were clear from the start, and it did not take long for airlines and manufacturers to consider reducing the number of engines. Aircraft such as the Boeing 720 had started to address the need for jets that could operate to smaller airports, but it maintained the fuel-hungry four-engine design.

The Boeing 727 was the next development from Boeing. It came about from joint requests from US airlines (American Airlines, United Airlines, and Eastern Air Lines) for a smaller jet to serve shorter flights and smaller airports.

The three-engine 727 was agreed as a compromise that would deliver better efficiency (and reduced operating costs) but still allow over-water flights to the Caribbean and operation at high-altitude airports. It entered service in February 1964 with Eastern Air Lines. It went on to be a success for Boeing, with 1,832 aircraft delivered. Amazingly, it is still in regular service. According to data from ch-aviation, there are 39 active 727s as of October 2023, used by 27 different operators.

Photo: Markus Mainka | Shutterstock.

McDonnell Douglas followed quickly with the narrowbody twin-engine DC-9 and later the three-engine widebody DC-10. The DC-10 was intended as a replacement for the quadjet DC-8. And Lockheed entered the large jet market with the L-1011 Tristar, a three-engine widebody.

Making quadjets larger – The Boeing 747

Making quadjets larger – The Boeing 747

The early run of quadjets peaked with the launch of the Boeing 747 in 1970. Although airlines had already started introducing two and three-engined jets for shorter flights, the quadjet still had a vital role to play.

Pan Am had worked closely with Boeing on the 707 and now saw the potential of a larger aircraft, offering a lower cost per seat. Development of the 747 began in April 1966, with Pan Am ordering 25 aircraft for $525 million.

Photo: Boeing

Boeing took part of the design from previous work on a US military transport proposal, a contract it ultimately lost to Lockheed and the C5 Galaxy. The iconic shortened upper deck was originally intended to be larger, but this did not meet safety and evacuation requirements at the time. It allowed the full use of the main deck for freight – a concept that went on to be a great success for the 747 series. And for passengers, it has offered an unrivaled space for a premium cabin or onboard lounge.

Photo: Boeing

The 747 has improved through several variants. The initial 747-100 was soon improved by the 747-200, with upgraded engines and cargo conversion ability. The 747-300 introduced a stretched upper deck but was short-lived (due to its popularity) and replaced by the improved 747-400 in 1989. This was the best-selling variant, with 694 aircraft delivered.

The 747-400 remained in production right up to 2009 (2005 for the passenger version). It propelled the 747 to the position of best-selling widebody until beaten by the twin-engine 777 in March 2018. The Boeing 747-8 kept the series going up to 2023, when the final 747 ever was delivered to Atlas Air.

Making quadjets faster

Concorde

The story of quadjets is not just limited to large, heavy jets. Supersonic commercial travel has to one of the major successes of the quadjet. Concorde used its four engines to reach its speed of Mach 2. Entering service in 1976, Concorde only ever flew with British Airways and Air France. There was earlier interest from several other airlines (with around 100 options from 18 airlines).

Photo: Graham Bloomfield | Shutterstock

Increasing costs, concerns about noise and environmental impact, and damage to supersonic hopes from the cancelation of Boeing’s supersonic project and an early crash of the Tu-144 were all contributing factors. This was further compounded by a general change in interest to larger, high-capacity aircraft (such as the 747) and the potential to offer lower fares.

Only 20 aircraft were built, and only 14 entered commercial service (seven with each of British Airways and Air France). It was, of course, an amazing achievement.

Photo: First Class Photography | Shutterstock

However, it was expensive to operate, and rising fuel prices made this worse. Ticket prices had to be high as a result, limiting its market. Airlines operated it at a profit, but governments never recovered their investment. Its fateful crash in 2000 may have marked the end, but its fate was sealed economically before that.

The Tupolev Tu-144

Concorde was not the only supersonic quadjet. The Russian-built Tupolev Tu-144 also pushed the possibility of four engines to supersonic flight. It used four Kolesov RD-36 engines (earlier models used less efficient Kuznetsov engines).

Following two fatal crashes, the Tu-144 was withdrawn from passenger service in 1978. But even before this, it had never been very successful. It only served on one route, Moscow to Almaty, and had a short range. It was also extremely inefficient, using afterburners at all times to maintain supersonic flights (Concorde only required this at certain points).

Supersonic will return, likely with four engines

And after a long gap, it is once again looking hopeful that supersonic travel will return. The next generation of supersonic jets will not necessarily need four engines. There are several aircraft in the design and prototype stage. Many of these will aim for supersonic with just two engines. For a long time, the largest of these – the Boom Overture aimed to use two or three engines. In 2022, the design was changed to four. Boom explained this to Simple Flying:

We selected a four-engine configuration after extensive R&D and efforts to understand the supply chain capabilities of our partners. Using four engines lets us shrink the size of each engine, allowing production to fall within current supply chain and manufacturing capabilities—all while reducing the noise levels of the aircraft.

Photo: Boom Supersonic

A regional quadjet – BAe 146

There is one more notable quadjet that served a different purpose. British Aerospace launched the BAe 146 regional quadjet in 1983. This remained in production until 2001, with 287 aircraft delivered (it later became the Avro RJ).

Its four turbofan engines were not for speed or a heavy airframe. They were intended to aid short-field performance. This not just provides extra power, but it increases redundancy in the event of engine problems allowing safe take-off at difficult airfields.

It has also been popular for its much quieter operation. The hi-bypass turbofan engines are quieter than similar jet engines, and with four engines, it can climb with less power. It has been popular at London City Airport for this reason.

Competition with twin-engine aircraft

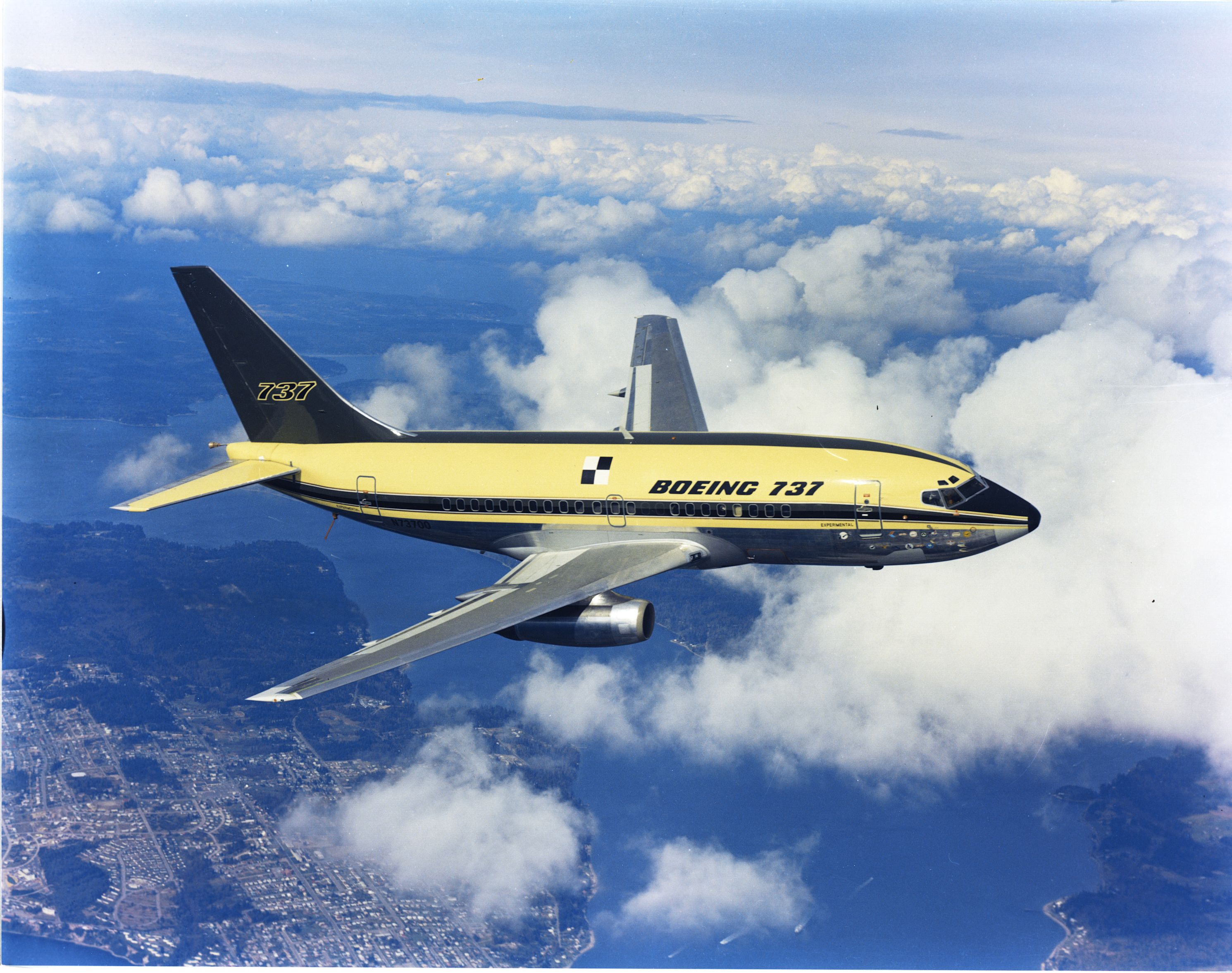

It did not take long for twin-engine jets to be introduced widely. Boeing built on the success of the narrowbody but four-engined, 707 with the three-engine 727 as we have discussed. And the Boeing 737 was launched in 1969, ultimately going on to evolve through several improving series and variants to become the best-selling aircraft of all time.

Photo: Boeing

The 727 and 737 were smaller capacity aircraft, though. The real challenges for quadjets began when widebodies starting moving to two engines.

The Airbus A300 and Boeing 767/777

Airbus launched the first twin-engine widebody aircraft, the Airbus A300, in 1974 (with launch customer Air France) as a competitor to the older Boeing 707 (and 727), filling the gap between the 737 and 747.

And it competed well. The Boeing 707 was ahead on range (9,300 kilometers for the 707-320B compared to 7,500 kilometers for the later A300-600) but had a higher capacity (247 compared to 141 typically). And, of course, it came with the efficiency and lower cost of flying on two engines. Sales were slow, but it went on to sell over 500 aircraft once its reputation improved.

Photo: Airbus

Boeing, of course, introduced twin widebodies, but not until 1982. The Boeing 767 entered service with United Airlines in September 1982. This initially focussed on transcontinental US routes, but with ETOPS improvements, it soon could fly further afield, eating into the advantages of the quadjets.

The larger Boeing 777 followed in 1995. This has taken the capacity and range of the twinjet even further, with the 777-300ER pushing range and capacity almost up to that of the 747-400.

Twin engines and ETOPS

The limitations of twin engines up to this stage were not just due to power, but also to their permitted range of operation. Until the 1980s, twin-engine aircraft were limited to operating up to 60 minutes from a suitable diversion aircraft (90 minutes in some locations). This, of course, severely restricted long-distance, and in particular, over-water use. This changed with the introduction of ETOPS (Extended-range Twin-engine Operational Performance Standards) in the early 1980s.

ETOPS came about with the realization (and evidence) that twin-engine flying was safer than first thought. Specific aircraft could be approved to extend the distance they flew from a diversion airport. The first rating of 120 minutes was given to Trans World Airlines with the Boeing 767.

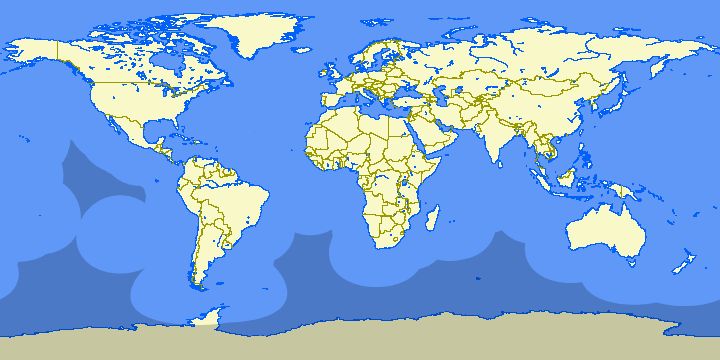

Ratings have improved significantly since then. The Boeing 777 was the first aircraft to have a rating of 180 minutes. An ETOPS 180 rating already covers 95% of the earth’s surface, allowing more efficient transoceanic routes (this is shown on the map below).

Image: GCMap

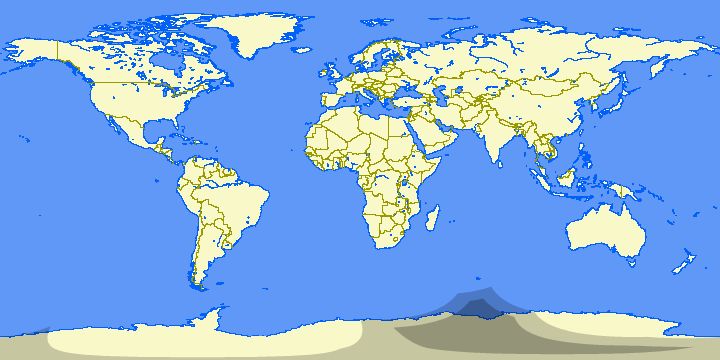

And ETOPS 240 was first given to the Airbus A330 in 2009, and the Boeing 787 later. The A350 now has the highest rating of ETOPS 370. With ratings as high as this, The only no-go area for twin-engine aircraft is directly over Antarctica.

Image: GCMap

The A340 – keeping choices for airlines

Despite the introduction of the twin-engine A300, 767, and 777, it was not all over for quadjets. Boeing had the 747 and Airbus launched a competitor with the Airbus A340. The twin-engine A330 and four-engine A340 were developed together, a smart move by Airbus that made the development of the A340 feasible, despite lower sales.

Photo: Airbus

Airbus saw demand still for both twins and quads. Airbus’ vice president for strategic planning, Adam Brown, explained this (in reporting by FlightGlobal):

“There was much internal debate whether to go with the big twin or the quad… North American operators were clearly in favor of a twin, while the Asians wanted a quad. In Europe, opinion was split between the two…The majority of potential customers were in favor of a quad despite the fact, in certain conditions, it is more costly to operate than a twin -they liked that it could be ferried with one engine out, and could ‘fly anywhere’ – remember ETOPS hadn’t begun then.”

Photo: Sudpoth Sirirattanasakul | Shutterstock

The A340 is sometimes thought of as a failure, with lower sales than other types and early retirement of young aircraft (Iberia, for example, retired its A340s with the youngest just ten years old). It wasn’t, though. It served a purpose at the time, brought quadjet competition for Boeing, and was efficiently developed alongside the A330.

The Airbus A380 and Boeing 747-8 – new hope for quadjets

Despite the increasing popularity and capability of twin engines from the 1980s, there was still a place for four engines with heavy airframes. The A340 program remained alive until 2011, although sales dropped with a growing preference for twins. In 2005, for example, Boeing sold 155 777s compared to Airbus’ 15 A340s.

The 747 filled this role for Boeing, remaining in production until 2023. The 747-8 launched in 2011 with Lufthansa and has gone on to sell 48 passenger models and 107 freighters. Despite the retirement of many 747-400 fleets, the Boeing 747-8 will keep the iconic aircraft in the sky for a few more years yet.

Photo: Vincenzo Pace | Simple Flying

Airbus launched the Airbus A380 in 2007 with Singapore Airlines. This was a troubling development, with costs mounting and delays leading to the dropping of a freighter version. But despite delays, it was a great achievement.

Its two decks boosted passenger capacity to around 575 (but with a maximum of 853 possible). For comparison, the 747-8 offers a typical capacity of 467 (and a maximum exit limit of 605). 14 airlines ordered the A380, with 251 aircraft sold. Almost half of these went to Emirates.

Photo: Plane Photography | Shutterstock

The decline of the A380

Unfortunately, the A380 has not worked as well as hoped. There are several reasons for its decline. In short, it is designed for a hub and spoke operating model, carrying high volumes of passengers on key routes. It works even better if these routes fly into capacity-constrained airports, where airlines can maximize slot use.

Photo: Jarek Kilian I Shutterstock

There is now more of a preference for point-to-point operations with lower-capacity aircraft. No US airline ordered the A380, all preferring instead to operate point-to-point models. Its size has also limited its use at many airports, something that the Boeing 777X has addressed with its folding wingtips.

And as a final complication, the economics of operating a small fleet has been tough. Just as with any aircraft, there are advantages in costs, maintenance, and scheduling of operating larger, similar fleets. Emirates has made this work for the A380, but many airlines have struggled with small fleets.

Quads lose out to twins

The shift to more efficient twin-engine aircraft is now well-established. Not only are no new quadjets planned, but the construction of current models has ended.

New aircraft being launched and planned for the near future are all twin-engine. The A350 is the latest offering from Airbus. The Airbus A350-1000 takes capacity up to 369. And Singapore Airlines ‘A350-900ULR pushes its range to almost 18,000 kilometers, beating any quadjet (the standard A350-900 offers 15,000 kilometers).

Photo: Fasttailwind | Shutterstock

The much-anticipated Boeing 777X will push the twin offering even further. The larger 777-9 will offer a typical capacity of 426, more than any twin yet. And it promises significantly improved efficiency over the 777-3000ER and A350 (according to Boeing). This is due to several innovations, including the largest engines yet developed for a commercial aircraft and folding wingtips to improve efficiency in the air but still allowing operation at many airports.

Photo: Vidit Luthra | Shutterstock

The 777X has seen several delays, but it is on the way. In total, 363 777Xs have been ordered across all variants, including the 777F. The largest order of 115 aircraft is from Emirates. Delivery is now expected to start in 2025, but Emirates is set to receive a proving aircraft in 2024.

Declining quadjets in 2023

The pandemic and the slowdown in aviation no doubt expedited the retirement of quadjets. We saw several airlines retire A340 and 747 fleets early (for the 747, this includes British Airways, KLM, Qantas, and Virgin Atlantic), and the A380 quickly fell out of favor (although many operators have now brought it back).

Photo: Bob L Parker | Shutterstock

To put the decline into context, Simple Flying looked recently at the data for active quadjets. Using data from Cirium showed that in September 2023 there were around 11,700 commercial flights scheduled to be operated by quadjets worldwide – this was down 44% versus 2019. And only 98 airports worldwide would see them.

Will we ever see another quadjet?

With no more four-engine aircraft on the commercial market, you have to question whether another will ever be launched.The supersonic Boom Overture, of course, is under development and will be a quadjet. But for larger, commercial widebodies twins are set to dominate.

If there a four-engine development again, it would most likely be to support the launch of a much larger, certainly twin-deck, aircraft. The issue of reliability and redundancy is no longer relevant. Currently, another large development seems unlikely. The A380 has certainly shown this. And with the popularity of point-to-point options for many airlines, and a twin the size of the 777X on the way, it is hard to see the need.

Would you like to share any thoughts on quadjets and their history? Which has been your favorite aircraft over the years? Let us know in the comments.

Sources: FlightGlobal, ch-aviation.com