Summary

- An assassination attempt on Chinese leaders led to an air crash, which prompted the Chinese people to decide to manufacture their own commercial aircraft for the first time.

- The earliest group of Chinese aircraft designers learned aircraft design knowledge from the Soviet Union during the brief period of Sino-Soviet friendship.

- Seeing the success of the Soviet Union in developing the Tu-104 civilian airliner from the Tu-16 bomber, China decided to develop the Y-10 based on the H-6 during the Cultural Revolution.

- The Y-10 became the first passenger aircraft developed by China.

On May 5, 2017, the focus of China’s civil aviation industry was entirely on Shanghai Pudong International Airport (PVG). That afternoon, the successful maiden flight of the China self-developed C919 aircraft marked a historic breakthrough for Chinese civil aviation.

Among the crowd at the first flight site was an elderly man with white hair, dressed in a black suit and leaning on a cane, closely watching the entire process. His name is Cheng Bushi.

Born in 1930, he began his aircraft design career in 1951, just two years after the founding of the People’s Republic of China. At the peak of his career, he served as the deputy chief designer of the Y-10 project, overseeing overall design, aerodynamic analysis, computing, and flight testing.

Photo: COMAC

However, due to various political factors during and after the dark period of the Cultural Revolution, the Y-10 project was ultimately shelved. Finally, at the age of 87, he witnessed the moment when China’s self-developed large passenger aircraft soared into the sky.

Over the more than 70 years since the founding of the People’s Republic of China, what kind of rocky path have the Chinese people traveled in developing large passenger aircraft independently, and what important role has the city of Shanghai played in this journey? To understand all this, we need to start with an air disaster nearly 70 years ago.

Chapter 1: The spark of tragedy

On April 11, 1955, at an altitude of 5,500 meters above the waters of Sarawak, Malaysia, a Lockheed L-749A Constellation, built by the American Lockheed Corporation, experienced an explosion in its right engine. Smoke and flames engulfed the cabin within seconds, sending the aircraft plummeting uncontrollably towards the sea. In a thunderous explosion, the plane shattered into three pieces, killing all eight Chinese passengers onboard.

This ill-fated aircraft was the “Kashmir Princess” of Air India, carrying members of the Chinese delegation en route to the Bandung Conference (first Asian-African Conference) in Indonesia. Originally, Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai was supposed to be among the passengers, but a last-minute change in his itinerary diverted him through Burma to Indonesia, sparing him from the fatal flight.

After the air disaster, China quickly dispatched personnel to investigate the incident. It didn’t take long for them to uncover the forces behind the tragedy: the assassination was orchestrated by the Kuomintang authorities in Taiwan. They bribed ground staff at Hong Kong’s Kai Tak Airport to plant a bomb in the right wing of the aircraft.

The catastrophe sparked a profound reflection among China’s top leaders. In an era of “self-reliance,” the incident underscored the need for China to manufacture its own civil aircraft. If China could produce its own passenger aircraft, its leaders would no longer have to rely on foreign aircraft for their travel, even to neighboring countries like Indonesia.

At that time, the world’s major powers had their own aircraft for their leaders, ensuring both security and a display of national strength. During the Cold War, planes symbolized not just practical utility but also prestige.

At the Geneva Summit in July 1955, Soviet Union leader Nikita Khrushchev was deeply impressed and envious when he saw US President Eisenhower’s Lockheed VC-121E. The massive aircraft, with its four engines and triple vertical tails, left a lasting impression on him.

Upon his return to the Soviet Union, Khrushchev immediately convened the country’s top engineers to develop a large aircraft. By early 1956, the world’s first successful jet airliner, the Tu-104, was born. It wasn’t driven by technological advancements or market demand but by the need to bolster the Soviet leader’s prestige during the Cold War.

Related

When The Soviet Tupolev Tu-104 Became The 2nd Jetliner In Service

The Tu-104, adapted from the Tu-16 bomber, featured powerful engines and a spacious cabin, quickly becoming a global sensation. Its sheer size and elegance captured the attention of the world, even the British Queen. As the pride of Soviet aviation, the Tu-104 became Khrushchev’s cherished toy, accompanying him everywhere.

In 1958, when Khrushchev visited China, his aircraft landed at Beijing Nanyuan Airport (NAY). Although the honeymoon period between China and the Soviet Union had ended, relations had not yet soured. With Soviet approval, China organized a visit for personnel in the aviation design field. The young aircraft designer Cheng Bushi later recalled, “I had never seen such a large aircraft.”

Other observers included Ma Fengshan, Zhao Guoqiang, and Zheng Zuodi – individuals from various military aircraft research institutes and manufacturing plants across China. Little did they know that they would come together years later to embark on the rocky path of China’s commercial aircraft industry.

Chapter 2: The Pioneers

In 1964, Xi’an Aircraft Manufacturing Factory undertook the task of converting the H-6 bomber to carry atomic and hydrogen bombs, following direct instructions from Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai:

“Any request could be made, but the mission had to be completed.”

The leaders of Xi’an Aircraft Manufacturing Factory candidly expressed that everything else was manageable, but they needed to borrow one person from Harbin Aircraft Manufacturing Plant – Ma Fengshan.

The entire Xi’an Aircraft Manufacturing Factory had long been acquainted with Ma Fengshan’s name. The plant’s security department kept a classified document called “Ma Fengshan’s Notes,” a meticulously kept notebook from his studies in the Soviet Union. Accessing it required political screening, and leaders had to personally vouch for the reader, who was not allowed to take notes, photograph, or keep the document overnight.

Ma Fengshan’s notes were a comprehensive, handwritten aviation design textbook, richly illustrated and detailed.

Born in Wuxi, Jiangsu Province, Ma Fengshan enrolled in the Department of Aeronautical Engineering at Jiaotong University in 1949, becoming part of the first generation of aircraft designers in New China. In September 1952, he graduated early to join Harbin Aircraft Manufacturing Plant.

In May 1959, Ma and a group of technicians went to the Tu-16 production plant in Kazan, USSR, to study. The Soviet experts were generous, reassuring their Chinese students that they didn’t need to take notes as all materials would be shipped to China by train later. Most of the students believed this and didn’t take notes.

Upon returning to China, the students never received the promised trainload of materials. The sudden shift in Sino-Soviet relations meant that the Soviet experts and their drawings were gone, leaving China in a lurch during a critical phase of the H-6 project.

Fortunately, Ma, proficient in Russian, had diligently taken notes, recording everything from static tests to structural design and key parameters. His notebook became a top-secret document, instrumental in the H-6 project, leading to Ma’s rapid promotion to deputy chief engineer.

Ma Fengshan, hailed as a top-tier talent, played a pivotal role in the H-6’s successful development. The aircraft performed China’s first hydrogen bomb test drop on June 17, 1967, becoming a mainstay in the PLA’s bomber fleet well into the 21st century. This success underscored China’s potential to follow the Soviet example: modifying bombers into jet airliners.

Chapter 3: The Dream of Y-10

It all began with a visionary idea. In the late 1960s, China had just successfully developed the H-6 bomber, drawing inspiration from the Soviet Union’s experience of converting the Tu-16 bomber into the Tu-104 airliner. With this triumph, the Chinese leadership saw an opportunity to venture into civilian aviation. The seeds of a dream were planted.

In the corridors of power, whispers of creating a jet-powered airliner started to emerge. Shortly after China produced its first H-6 bomber entirely in-house, which made its maiden flight on December 24, 1968, Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai himself inquired in 1969 about the feasibility of developing a jet-powered aircraft on the H-6 platform.

In 1970, during the Cultural Revolution, Chairman Mao Zedong, who held an almost divine status, visited Shanghai. Impressed by the city’s industrial capabilities, he remarked,

“Shanghai’s industrial foundation is very strong; you can build airplanes here!”

When it comes to the conditions for building airplanes, Shanghai at the time was actually not as well-equipped as Shenyang and Chengdu for building fighter jets, Xi’an for building bombers, or Hanzhong for building transport aircraft.

Shanghai didn’t have an aviation industry at that time. The city’s experience with airplane manufacturing could only be traced back to the early 1930s when the Nationalist Navy set up an aircraft manufacturing department, producing about 20 seaplanes. However, the supreme leader’s instructions were beyond any doubt.

Under the collaborative efforts of Shanghai, the Third Ministry of Machinery Industry (later the Ministry of Aviation Industry), and the Air Force, the project advanced at an unprecedented pace. In the eighth month of 1970, the passenger aircraft project was officially launched and dubbed the “708 Project,” later renamed the Y-10 project.

China’s aviation resources and talent began concentrating in Shanghai. Engineers from across the country, including Ma Fengshan, were relocated to lead the Y-10 project. Shanghai Aircraft Manufacturing Factory took charge of assembly, while various local factories handled different components, coordinating efforts nationwide to tackle this monumental challenge.

Thus, began one of the most magnificent, tumultuous, and poignant chapters in the history of China’s aviation industry.

Chapter 4: The Lament of the Y-10

The vision behind the Y-10 project was not merely to develop a commercially viable aircraft but to create a dedicated aircraft for China’s top leadership. Despite the immense support garnered from the highest echelons of power, the journey of Y-10’s development was fraught with challenges.

The fervent desire for achievement led to the establishment of special task forces among the Shanghai leaders, treating the project as a means to political capital. These groups meddled incessantly, imposing unrealistic demands and constraints. From designing lavatories to determining the number of engines based on loyalty to Chairman Mao, the project faced a barrage of absurd requests.

As chief designer, Ma Fengshan navigated these challenges with resilience and innovation. He united a diverse array of talents, from persecuted veterans to budding young minds, instilling trust and fostering collaboration. During the chaos, Ma Fengshan’s leadership remained steadfast, combining daring innovation with respect for scientific principles.

The working conditions were as harsh as the challenges they faced. Designers toiled away without fixed workspaces, utilizing whatever flat surface they could find – a cafeteria, a shipping container, or an abandoned terminal. Despite the hardships, the team’s commitment to excellence never wavered.

Ma Fengshan left his wife and daughter behind in Xi’an and dedicated himself to the project, often working late into the night.

Against this backdrop, the Y-10 project reached critical milestones. The meticulous attention to detail and unwavering commitment to quality ensured that errors were minimized even amid political turmoil.

In November 1978, the first Y-10 aircraft passed static strength tests in Xi’an. In July 1979, the WS-8 engine completed 1000 hours of testing. By December 1979, major systems simulation tests were successfully completed. And in August 1980, preparations for the maiden flight commenced.

The anticipation surrounding the maiden flight of Y-10 was palpable. On September 26, 1980, with the stirring strains of Beethoven’s “Heroic Symphony,” the Y-10 aircraft took to the skies. Ma Fengshan assured the safety of the Y-10’s first flight by being willing to fly onboard. It was a momentous occasion, a testament to the resilience and ingenuity of China’s aviation pioneers.

Chapter 5: The beginning of the end

However, the accolades and celebrations that typically accompany such achievements were conspicuously absent. Despite its groundbreaking success, Y-10 remained shrouded in silence within China’s media landscape. The deafening silence was a bitter pill for Ma Fengshan and his team to swallow.

The Y-10 project, known as the “708 Project,” during the Cultural Revolution, had remained largely unnoticed by Western nations. However, after the 1978 China Open Reforms, foreign aviation giants began to take note of China’s significant achievements. The Y-10’s successful maiden flight in 1980 caught the world’s attention. Reuters remarked that such advanced technology signaled China’s emergence from backwardness. The International Herald Tribune quoted McDonnell Douglas executive J.C. Brizendine, who lauded China’s leap in aircraft manufacturing.

Yet, back home, voices of skepticism and doubt began to surface. Rumors of plagiarism and political interference tarnished the project’s reputation, casting a shadow over its accomplishments.

Despite these accolades, the Y-10’s story remained untold within China. Domestic media silence continued even as the aircraft flew successfully to major Chinese cities between 1981 and 1983.

Despite these setbacks, the Y-10 team continued to fight for their project. In early 1984, a severe snowstorm in Tibet created an opportunity. The Y-10 team volunteered their aircraft to deliver relief supplies, successfully gaining approval after persistent efforts.

On January 31, 1984, Y-10 (02) took off from Chengdu Shuangliu Airport (CTU) in Sichuan Province to Tibet. It became the first Chinese-made aircraft to land at Lhasa Gongga Airport (LXA) at an altitude of 3,570 meters. Over the next seven days, the Y-10 made six round trips to Lasha Gonggar Airport (LXA), transporting over 40 tons of relief supplies to the disaster-stricken region. The Tibet Autonomous Region government expressed its gratitude with a banner inscribed, “Sincere thanks for the valuable support.”

After its final mission, the Y-10 was grounded permanently at the Shanghai Aircraft Manufacturing Plant. It became a silent witness to its birthplace, left to decay. The unfinished Y-10 prototype (03) was abandoned. The production lines for the Y-10 were dismantled to make way for the MD-82, and all production equipment was sold as scrap.

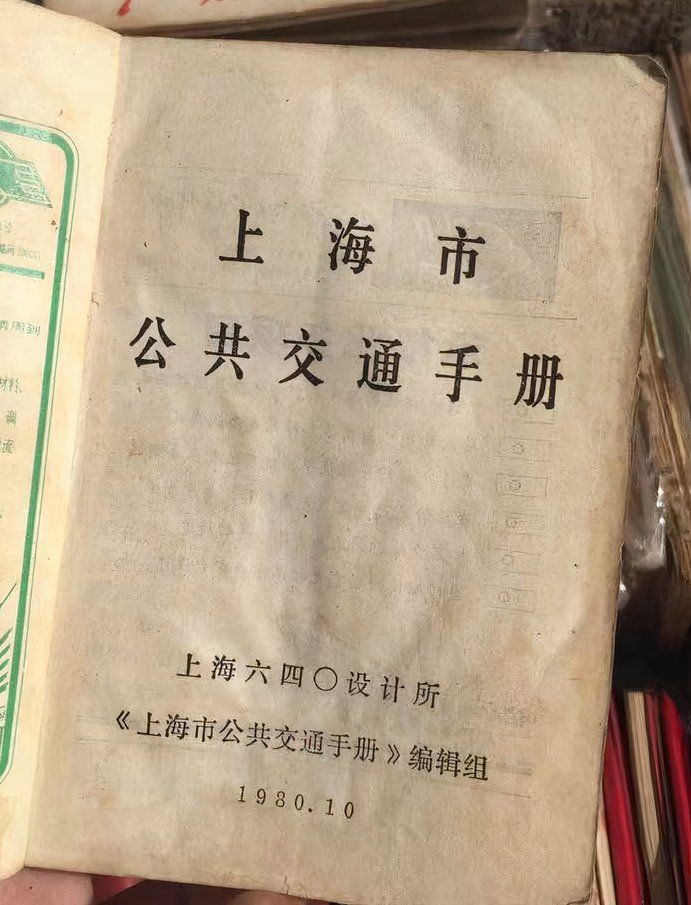

Alongside that, an entire generation of aircraft design talent was wasted. According to Deputy Chief Engineer Cheng Bushi, some designers, finding no work in aviation, were reassigned to create and sell Shanghai traffic manuals, a tragic waste of the country’s top industrial minds.

Photo: Su Wu

Ultimately, the fate of Y-10 was sealed long before its maiden flight. Decisions were made in the corridors of power that would determine the project’s future. Despite the triumphs and tribulations, Y-10’s legacy endures – a testament to the indomitable spirit of those who dared to dream amid the tumultuous currents of history.

The Y-10 project’s premature end marked a significant setback for China’s aviation industry, a dream stifled by political and economic currents, leaving behind a legacy of what could have been.

Please stay tuned for Part 2, which will include the following chapters:

– Chapter 6: Follow the automobile industry: “Technology for Market”

– Chapter 7: Turning to Airbus: Another Failed Attempt

– Chapter 8: Rising from the ashes: the ARJ21 Program

– Chapter 9: A New Dawn: the C919 Program