Summary

- China’s partnership with McDonnell Douglas to develop aircraft failed due to high costs and Boeing’s acquisition, causing financial losses and a pivot to Airbus.

- After the MD-90 failure, China partnered with Airbus on the AE100, but high costs, transparency issues, and market misalignment led to its termination, raising doubts about China’s aircraft development capabilities.

- After abandoning large aircraft development around 2000, China launched the ARJ21 regional jet project in 2002, aiming to revive its aviation industry and bridge a significant technology gap.

- China’s aviation industry advanced with COMAC’s founding in 2008 and the successful 2017 flight of the C919, embodying a shift towards self-reliance and honoring pioneers like Ma Fengshan.

In our previous article, “China’s Commercial Aviation Odyssey: From The Y-10 To The C919 – Part 1,” we explored the tumultuous yet pioneering journey of China’s civil aviation industry, particularly focusing on Shanghai’s instrumental role.

The narrative begins with the 1955 air disaster (failed assassination) that catalyzed China’s resolve to develop its own passenger aircraft, marking the start of an arduous path toward aviation independence. We followed the early contributions of key figures like Ma Fengshan, whose dedication and expertise were pivotal in the development of the H-6 bomber, setting the stage for future projects.

The ambitious Y-10 project, launched at the peak of dark Cultural Revolution times, symbolized China’s aspirations to create a jet-powered airliner. Despite overcoming numerous technical and political challenges, the project was ultimately shelved in 1984 due to political and economic factors, reflecting the complex interplay of innovation and adversity in China’s civil aviation history.

This sets the scene for the continued evolution of the industry, which will be explored in the subsequent chapters.

Related

China’s Commercial Aviation Odyssey: From The Y-10 To The C919 – Part 1

The Shanghai Y-10 went from a flawed beginning to a tragic end.

Chapter 6: Follow the automobile industry: “Technology for Market”

In 1984, China stood at a pivotal historical juncture. That same year, Shanghai Automotive and Germany’s Volkswagen established a joint venture, marking the formal commencement of China’s “technology for market” strategy to attract foreign investment. This collaboration heralded a new era, as the Volkswagen Santana became emblematic of the burgeoning automotive market in China.

As this successful model unfolded in the automotive sector, the Aviation Industry Ministry aspired to replicate it within the aviation field. They chose McDonnell Douglas from the United States as their partner, hoping to make the MD-82 aircraft the “Santana” of China’s civil aviation industry.

At the time, McDonnell Douglas was struggling to compete with Boeing and saw China as a vital market to potentially overtake Boeing. They demonstrated significant sincerity, sending numerous technical staff and design reports to China, aiming to establish a strong foothold through this collaboration. However, despite assembling the MD-82 in China, the design and production of key components remained under American control.

As the state introduced the MD-82 assembly line, Ma Fengshan, already gravely ill, repeatedly emphasized the importance of independent research and development. Unfortunately, his views were disregarded, leading to the disbandment of the Chinese commercial aircraft development team that had been united by the Y-10 project.

In the 1990s, the Ministry of Aerospace Industry formulated a “three-step” strategy for autonomous aircraft design and manufacturing. However, internal conflicts of interest among various departments hindered its implementation.

They fiercely debated priorities, such as whether to focus on planes with over or under 100 seats, and whether to partner with Boeing or continue with McDonnell Douglas. These disputes delayed the feasibility report submission until early 1992, nearly three and a half years later, filled with anecdotes emblematic of the era’s complexities.

For example, Zhao Guoqiang, responsible for the Y-10’s exterior design, recalled how plans abruptly shifted from Boeing to McDonnell Douglas due to a ministry leader’s personal dissatisfaction with Boeing’s hospitality.

Photo: Boeing

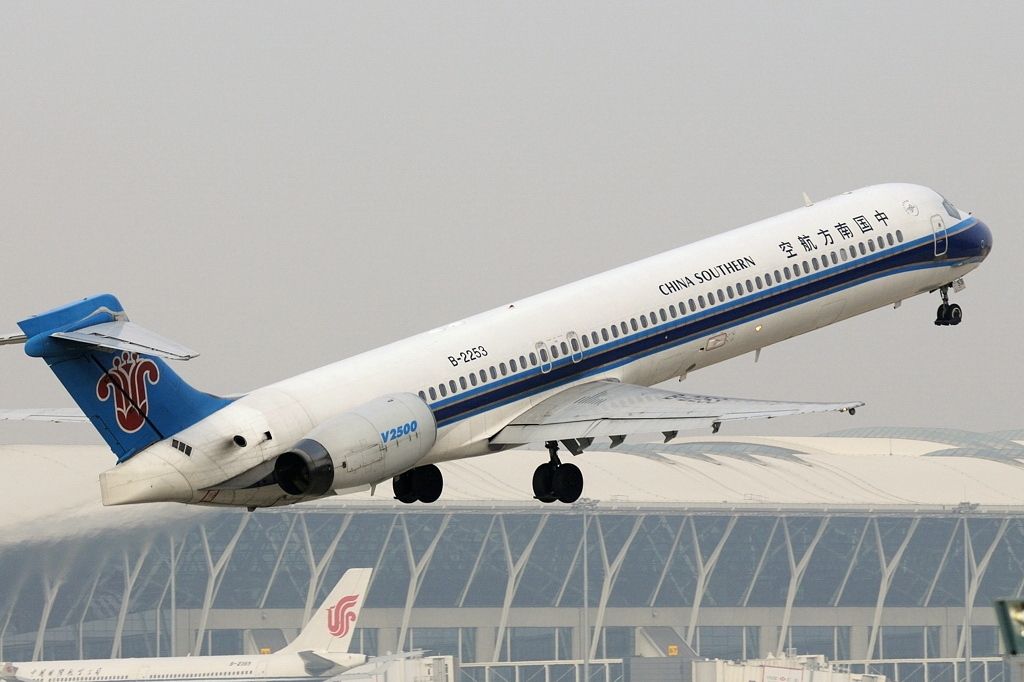

When cooperation with McDonnell Douglas on the MD-90 was finalized, the Civil Aviation Administration of China (CAAC) mandated that domestically produced aircraft be sold at international market prices to avoid financial burdens on the civil aviation sector.

However, since the cost of producing an MD-90 at the Shanghai Aircraft Factory exceeded the cost of production at McDonnell Douglas in the United States, this rule doomed the MD-90 program to financial losses from the beginning.

In 1997, McDonnell Douglas was acquired by Boeing, which announced the discontinuation of McDonnell Douglas aircraft production. Before long, the CAAC declared they would not purchase discontinued planes, leading to the simultaneous halt of the MD-90 project.

This abrupt decision left China’s aviation industry in disarray. They had already invested heavily in materials and equipment for the MD90, and years of effort and financial outlay were rendered futile overnight.

At the time of the project’s termination, the first MD-90 was in the critical assembly stage in Shanghai. Unlike other factories with military orders, Shanghai Aircraft Factory faced a financial crisis, with thousands of employees confronting potential layoffs.

Despite limited funds and wages below Shanghai’s average, employees worked tirelessly, managing to complete two MD-90s before the project’s end. Tragically, three workers died during the rush to meet deadlines.

Following the MD-90 project’s failure, Boeing demanded that China destroy all related documents and announced that any continued use of the technology would be illegal. This colossal investment ended in nothing, causing profound grief among Chinese aviation experts. Nevertheless, undeterred by this setback, they turned their attention to Europe and Airbus.

Chapter 7: Turning to Airbus, another failed attempt

With the sorrow of the MD-90 project being terminated, the Chinese aviation industry set out again, this time turning their attention to Europe’s Airbus company. Ironically, Airbus was established in December 1970, two months after the inception of the Y-10 project.

At that time, the 100-seat aircraft market was a void in the civil aviation sector, with no firm monopoly established. Struggling to penetrate the Chinese market, Airbus expressed its willingness to create a brand-new aircraft tailored for the Chinese market, to be manufactured and assembled in China.

Photo: balipadma/Shutterstock

Under the Airbus Group, French Aerospatiale, British Aerospace, and Italy’s Alenia Aeronautica formed the “Asian International Aircraft Company” (AIA) to support this endeavor. Faced with the choice between independent development and technology importation, China once again chose technology importation, deciding to collaborate with Airbus on the AE100 project.

After signing a deal with Airbus and buying 30 A320 family aircraft, the situation for cooperation took a sharp turn. Airbus initially proposed a technology transfer fee of more than $1 billion, but would not disclose specific details of the technology transfer project outlined in the offer. The lack of transparency has prevented negotiations from reaching a substantive stage.

At the same time, the CAAC believed that the AE100’s 100-passenger capacity was too small compared to the Boeing 737, which typically seats 140 passengers, resulting in higher operating costs per passenger. As a result, they were reluctant to buy. Moreover, if China, the target market for the indigenous aircraft, refuses to buy it, the prospects for exports to other Asian regions will become even bleaker.

Despite initial enthusiasm, the cooperation failed to advance for a long time. Eventually, Airbus terminated the AE100 project, but soon invested in their own 107-seat A318, further frustrating the Chinese efforts.

Photo: Air France

The failure of the AE100 project has intensified the debate that China cannot develop an aircraft on its own. The media often highlighted that the project took three years and cost $300 million without any tangible results, which frustrated the public and the government.

Chapter 8: Rising from the ashes: the ARJ21 Program

After several decades of unsuccessful attempts, the Chinese central government no longer wished to make efforts to develop large aircraft independently. Coupled with the significant financial investment required for developing an aircraft, around 2000, Chinese Premier Zhu Rongji even privately said in a small circle that if anyone wanted to develop a large passenger aircraft, they would have to do so “over his dead body.”

Against this backdrop, Chinese aviation professionals made one last effort. They proposed independently developing a regional jet and stated that the project’s initial funding would be 5 billion RMB, requesting only half of that, 2.5 billion RMB, from the central government, while they would find the remaining funds themselves. This project eventually became known as the ARJ21 (Advanced Regional Jet for the 21st Century).

In September 2002, the ARJ21 project, a 70 to 90-seat regional jet, was officially launched. The aviation industry viewed this as their last opportunity, and both industry insiders and outsiders had high hopes for its success. After numerous setbacks and failures, China’s civil aviation industry could not afford any more disappointments.

The team leading the ARJ21 project consisted of veterans from the Y-10 days. Chief designer Wu Xingshi, deputy chief designer Zhou Jisheng, and aerodynamic designer Zhao Guoqiang had all once served under Ma Fengshan.

The research and design team presented a poignant picture: mostly individuals in their fifties and sixties with gray hair or young people in their twenties and thirties, with a significant gap in the 40-something age range. An entire generation of talent had not been cultivated.

The hopes placed on the ARJ21 project extended far beyond the aircraft itself. Zhao Guoqiang’s perspective echoed the aspirations of the Y-10 generation:

“With this project, we can gather a new generation for China’s civil aircraft manufacturing. We old guys, who are lucky to still be alive, can pass on our knowledge and skills, ensuring the continuity of the civil aviation industry. This is crucial for our nation. Otherwise, our descendants might face a blank slate in civil aviation, unable to rebuild from scratch. If that happens, our generation will have failed history.”

Photo: COMAC

In its day, the Y-10 project narrowed the gap between China and the global aviation industry to 15 years. By the time the ARJ21 took off, the gap had widened to 40–50 years. Wu, Zhou, and Zhao joined the Y-10 project in their twenties and thirties. By the time they were older and had graying hair, they were determined to once again bridge the gap, carrying forward the legacy of their late leader, Ma Fengshan.

Chapter 9: A New Dawn: the C919 Program

The ARJ21 project was not the final chapter for China’s civil aviation industry. In 2007, riding on the momentum of rapid economic growth, China’s central government approved the development of large aircraft and established the Commercial Aircraft Corporation of China (COMAC) in 2008.

The largest shareholder of COMAC was the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC), followed by the Shanghai municipal government. This resilient city, with its storied aviation history, once again stood at the forefront of China’s aircraft localization efforts.

With significant funding and support from the central government and the Shanghai municipal government, the new entity spearheaded the development of the 190-seat C919 aircraft. The C919 successfully flew on May 5, 2017, and has received nearly 1,000 orders so far, marking a major achievement for China’s aviation industry.

Photo: Aerospace Trek | Shutterstock

Ten years ago, on May 23, 2014, Chinese President Xi Jinping visited COMAC. While speaking at its design and research center, he stated,

“To become a strong nation, we must advance our equipment manufacturing industry and develop our own large aircraft, as it plays a leading and symbolic role.”

He emphasized that China, being the largest aircraft market, should reverse the old logic of “It’s better to buy than to build” to “It’s better to build than to buy.” He called for more funds to be invested in research and development, as well as manufacturing, of China’s own large aircraft.

It took decades for China to reach a consensus on the importance of manufacturing its own large aircraft. Unfortunately, Ma Fengshan did not live to see this day.

On September 27, 1984, Ma Fengshan, then only 55 years old and not yet at retirement age, was removed from his positions as Director and Chief Engineer of the Shanghai Aircraft Design and Research Institute. His health had already deteriorated due to the stress and disappointments he faced. In April 1990, Ma Fengshan passed away in a hospital in suburban Shanghai, at the age of 61. His ashes are interred at Longhua Cemetery.

Because the Y-10 never entered full production, Ma Fengshan did not receive any national scientific awards, nor was he elected to the Chinese Academy of Sciences or the Chinese Academy of Engineering. The Y-10, to which he devoted his life, sat quietly at the Shanghai Aircraft Factory, just 15km north of his resting place, until it was moved in 2017 to Shanghai Aircraft Manufacturing Conpany’s new site near Pudong Airport.

In April 2005, on the 15th anniversary of Ma Fengshan’s death, his former subordinate and the chief designer of the ARJ21, Wu Xingshi, wrote a 6,000-word tribute in his memory. On the day of the C919’s maiden flight in 2017, the 72-year-old Wu Xingshi simply remarked, “I am fortunate to have worked with such courageous people.”

In May 2019, on the 90th anniversary of the birth of Ma Fengshan, the chief designer of the Y-10, COMAC erected a bronze statue of him at its research center in Shanghai. The unveiling ceremony was attended by COMAC Chairman He Dongfeng, Ma Fengshan’s children, and Ma’s former colleagues, including Cheng Bushi and Wu Xingshi.

During the ceremony, Cheng Bushi stated:

“As history undergoes changes and things move forward, on this 90th anniversary of Comrade Ma Fengshan’s birth, I hope that we can inherit and uphold what has been proven correct in our past practices, while also embarking on new explorations to pioneer new territories. This will enable our cause to continuously advance.”

Ma Fengshan’s spirit continues to be passed down to a new generation of Chinese aerospace engineers, and the establishment of COMAC undoubtedly provides the best stage for this inheritance. Despite facing daunting challenges, the essence of this spirit can be summarized in just three words: never give up.

This spirit has been immortalized in a sculpture erected at COMAC’s Pudong manufacturing base; standing beside it, quietly parked, is the Y-10 aircraft, Prototype 02.

Photo: COMAC

.jpg)