Summary

- Aerial combat in WWI began with zeppelins and fighter planes armed with machine guns and bombs, like the Sopwith Camel.

- Balloons made a significant contribution to the American Civil War before the advent of powered flight by the Wright brothers.

- Thaddeus Lowe, considered the father of military aerial reconnaissance in the US, led the Union Army’s Balloon Corps during the Civil War.

As any serious student of military aviation history knows, aerial combat made its debut during the First World War, in the form of lighter-than-air zeppelins and heavier-than-air fixed-wing fighter planes and bombers alike, wielding machine guns and bombs alike.

Related

Snoopy’s Dream Plane: Why The Sopwith Camel Is Britain’s Most Famous Fighter Of WWI

The Sopwith Camel is Britain’s most iconic WWI fighter. Partially for its real-world achievements, and partially thanks to a beloved cartoon dog.

However, WWI wasn’t the first war in which aerial technology played a major role. Five decades prior — and four decades prior to the Wright Brothers’ first heavier-than-air powered flight, balloons made a key contribution in the American Civil War.

Related

120 Years Before The Wright Brothers: The Story Of The World’s First Balloon Flight

The first lighter-than-air crewed flight took place in France long before the Wright brothers’ famous first flight.

Speaking of the Wright Brothers, read more here about the ongoing debate about whether they truly made the first airplane flight.

The Mastermind: Thaddeus Lowe

Thaddeus Sobieski Constantine Lowe (August 20, 1832 – January 16, 1913) AKA Professor T. S. C. Lowe, was the genius to whom the Union Army became duly indebted. (As a personal sidebar, I cannot help but note with pride that the good professor and I share the same birthday, and for good measure, his two middle initials coincide with those of my undergraduate alma mater!)

As noted by the American Battlefield Trust (ABT; formerly known as the Civil War Preservation Trust [CWPT]) in an article from their Head-Tilting History series:

“Balloon aficionado Thaddeus Lowe was named Chief Aeronaut for the Union Army in late summer of 1861, after sending President [Abraham] Lincoln a telegram describing the view from 500 ft [152.4 m] above Washington, DC, in a balloon demonstration. Lowe was responsible for all aspects of Union balloon operations – transporting, maintaining, filling and manning the seven balloons he designed and constructed for the war effort.”

Thus, it came to be that Prof. Lowe is considered the father of military aerial reconnaissance in the United States, and the Library of Congress even goes so far as to say that “today he is known as the father of the Air Force.” (Though speaking myself as a former U.S. Air Force officer, I don’t recall Thaddeus Lowe’s name being mentioned during either my enlisted USAF Basic Military Training [BMT] or Officer Training School [OTS] classes.)

As noted by the National Park Service (NPS), the first nation to test out the use of balloons for military purposes was France. This happened in 1794 when the French Committee of Public Safety created the Corps d’ Aerostiers (“Aerostatic Corps”). The Corps sporadically used the balloons for reconnaissance during the French Revolutionary Wars, seeing action during the battles of Charleroi and Fleurus.

The proving grounds (and skies)

Luckily for Prof. Lowe, Abe Lincoln was a very open-minded, forward-thinking commander-in-chief, open-minded to any technologies that would contribute to winning the war and thus restoring and preserving the Union. Hence, not only did Thaddeus Lowe get tabbed Chief Aeronaiut, but, for good measure, a dedicated Union Army Balloon Corps was created, officially activated in October 1861. However, Lowe did not receive a direct commission, and instead maintained civilian status for the entirety of the Balloon Corps’ existence (which ended up stirring resentment amongst some of the senior Union Army officers).

Prof. Lowe built a total of seven balloons. The first three listed were single-man occupancy, whilst the remaining four were used for carrying more weight, such as a telegraph key set and anywhere from two to five people:

- Eagle

- Constitution

- Washington

- Union

- Intrepid (Lowe’s personal favorite of the bunch; later became the namesake of a U.S. Navy aircraft carrier)

- Excelsior (not to be confused with the Federal starship from “Star Trek III: The Search for Spock“)

- United States (this one was never actually put into service)

Intrepid and Union were the biggest of the bunch, with a capacity of 32,000 cubic feet (906.14 m³) of lifting gas, and could reach an altitude of 1,000 feet (304.8 m). The lifting gas in question was supplied by special hydrogen-generating inflation wagons, or by diverting gas from nearby municipal lines.

The balloons ended up being used for reconnaissance or directing artillery fire on enemy positions; the balloons’ operators would use signal flags or telegraphs to relay information to the troops on terra firma. Regarding the reconnaissance mission, ABT notes the following:

“When the balloons were in the sky, there was nothing secretive about them. They were often brightly colored with patriotic designs. While this might sound risky, the balloons were always positioned well behind the front lines at an altitude of near [sic] 1,000 feet, which made them difficult or impossible to shoot down. Lowe’s designs were intended to intimidate the Confederates by making them feel the Union Army was nearby, watching.”

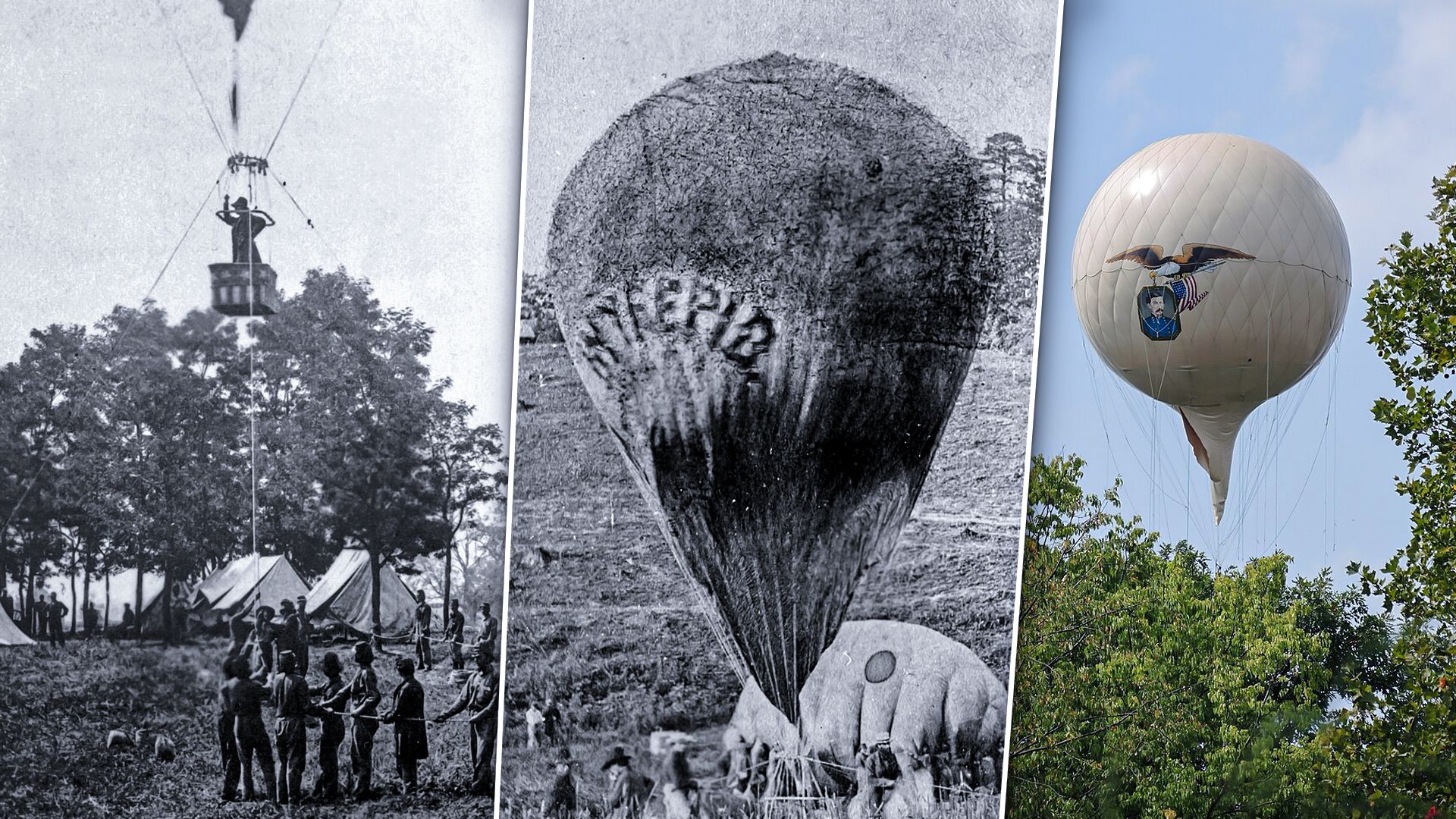

In other words, long before George Orwell came up with “Big Brother Is Watching You” for his classic dystopian novel “Nineteen Eighty-Four,” Thaddeus Lowe sent a not-so-subtle message to the Rebels that “Big Yankee Is Watching You.” Indeed, you can see on this modern-day replica of the Intrepid what appears to be a likeness of Union General George Brinton McClellan:

According to NPS, the majority of American Civil War balloon deployments took place in the Eastern Theater, especially during the Peninsula Campaign and the Seven Days battles (from March to July 1862), although on at least one occasion, balloons were used in the Western Theater during the Battle of Island Number 10 (February 28 to April 8, 1862).

Regarding the Peninsular Campaign in particular, the aforementioned 1,000-foot altitude of Prof. Lowe’s balloons proved to be a major source of frustration for the Confederates, as the “Johnny Rebs” made multiple futile efforts to shoot the balloons down with their artillery, and dramatized in the 1982 TV miniseries “The Blue and the Gray“:

Much to the Southrons’ consternation, not only did the Northern balloons survive the artillery barrages unscathed, Lowe’s view from above helped the Union discover the Rebel army’s evacuation from Yorktown.

In addition, according to Military History Now, balloons made at least a minor contribution to the Union’s ultimate success during the Siege of Vicksburg (a crucial victory that was finalized on July 4, 1863; the 88th birthday of the United States of America **and** the day after the Union’s equally crucial victory at the Battle of Gettysburg), and in the process, may have possibly made a mark on naval history as well as aeronautical history:

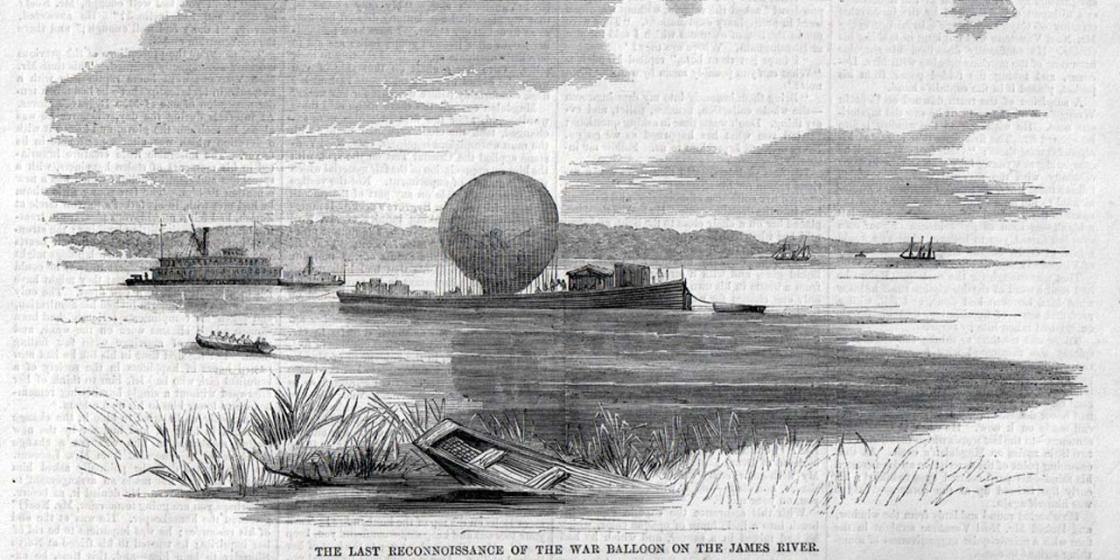

“During the U.S. Civil War, Union balloonists came up with a novel way to create the first mobile airships. They tethered a balloon to a modified barge and floated it down the Potomac River. This allowed observers to survey more enemy territory. The same method was employed at the Siege of Vicksburg on the Mississippi River. Could these balloon barges hold claim to being **the first aircraft carriers**?” [emphasis added]

Yet in spite of these successes, neither the Union Balloon Corps nor Thaddeus Lowe’s career lasted for the duration of the Civil War. Part of it was the aforementioned resentment of Lowe’s civilian status by senior Union officers, and what’s more, as ABT notes:

“It seems the Union determined that the limitations outweighed the advantages, and the Balloon Corps was disbanded in 1863. What remained of the war would be fought by land and water, and balloons would drift forever into the camp of light entertainment.”

Confederate Balloons

Though the title of this article is focused on the Union Army’s balloons, in the interest of “equal time,” or being “fair and balanced” (as Fox News likes to say), it must be acknowledged that the Confederacy used balloons as well. To use a military cliché, “The enemy gets a vote,” and “Johnny Reb” was more than willing to cast his proverbial ballot against “Billy Yank,” or to put it another way, adding literal balloons and bullet boxes to the metaphorical ballot box.

The ABT article elaborates thusly:

“Tugboat + balloon sounds like the cutest military-technology combo ever, but it was also an effective way for Confederate artillerist Edward Porter Alexander to monitor Union movement toward the James River during the Seven Days campaign. This innovative use of the Gazelle, the Confederacy’s only balloon, was cut short when the tugboat ran aground below Malvern Hill and Alexander and crew were forced to flee, leaving balloon and boat behind.”

One might reasonably ask why the Confederates built only one military balloon versus the Federals’ seven. The oversimplified answer is that the South had nowhere near the financial resources of the North. Digging deeper, the South was hampered in its capacity for building gas-filled silk balloons due to the inability to obtain any imports–a testament to the effectiveness of the Federal naval blockade of “Dixieland.” In the spirit of “Adapt, Improvise, Overcome,” the Southrons assembled their lone balloon — the aforementioned Gazelle — out of dress silk!

The design credit belonged to Dr. Edward Cheves of Savannah, Georgia; Dr. Cheves had the silk material sewn together by seamstresses and then covered the silk material with a varnish made by melting rubber in oil. From there the balloon was pumped full of coal gas and launched from a railroad car. (Cue the late Vivien Leigh as Scarlett O’Hara in “Gone With the Wind“: “Oh, fiddle-dee-dee!”)

Where are they now?

As far as I can ascertain, none of the American Civil War balloons from either side of the conflict were preserved for historical posterity. The replica of the Intrepid that you see in the photo headlining this article was exhibited at the Genesee Country Village and Museum in Wheatland, New York, at some point in time, but the museum’s website comes us blank when entering “Intrepid” or “balloon” into the search engine. Meanwhile, in 1983, the U.S. Postal Service honored the Intrepid with a postage stamp.