Summary

-

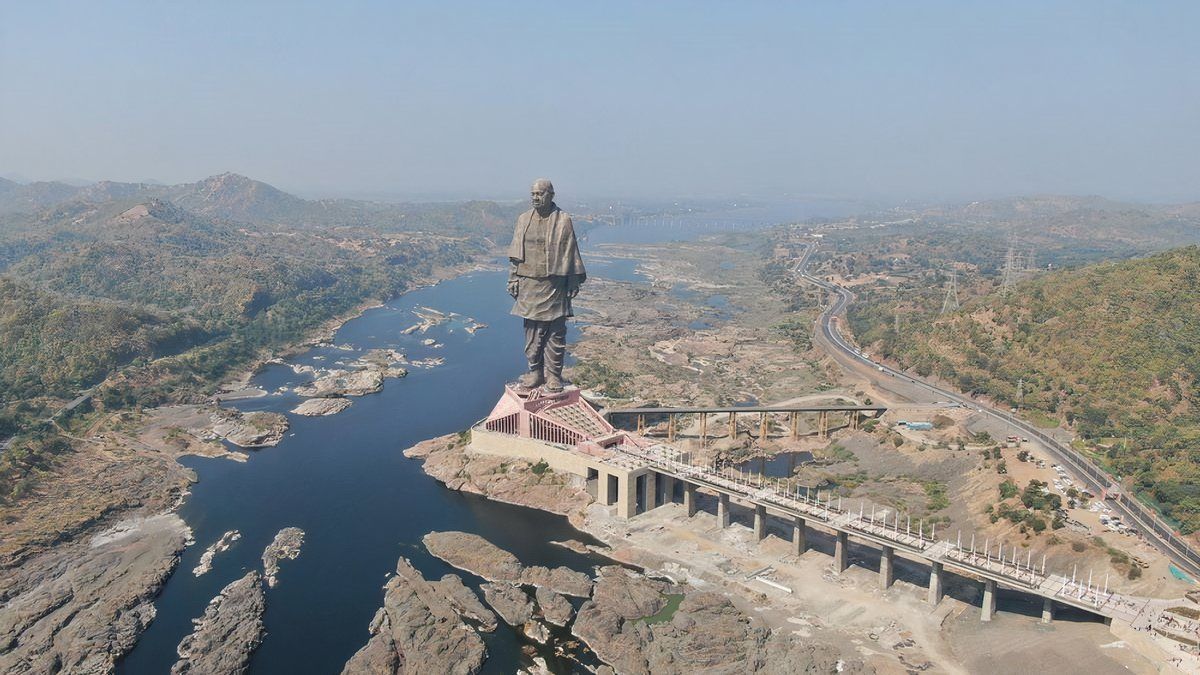

Photo: Gujarat Government

Back in 2020, SpiceJet launched a seaplane service in Gujarat, but faced issues with aircraft maintenance that lead to suspension of the service.

- A second attempt by MEHAIR to operate seaplanes on the same route was delayed and then canceled, showing challenges in establishing sustainable services.

- Despite governmental support, seaplane services in India have struggled to succeed due to high operational costs.

Seaplanes have been a feature of commercial aviation almost as long as humans have had powered flight. The first seaplane flight in 1910 rapidly led to the era of the sumptuous Pan Am Clippers in the 1930s and 40s, when taking off from and landing on water was the norm. Today, we think of modern seaplanes as smaller aircraft that specialize in connecting the more remote regions of the world.

We certainly don’t think of mainstream airlines expanding into seaplane operations. So it was surprising when SpiceJet, the Indian low-cost airline, decided to do just that. Even more extraordinary is that it happened at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, when airlines were cutting services rather than inaugurating new ones. So what was SpiceJet thinking, and what ever happened to their seaplane service?

Related

Spicejet To Launch Its First Seaplane Service

The new seaplane service is launched

Seaplane service was not a new thing for SpiceJet. The operator had run trials of seaplane services across India since 2017. Commercial operations were propelled forward when it secured 18 seaplane routes under the UDAN scheme, a regional airport development program of the Government of India that is focused on providing regular flights to 425 unserved, under-served, and mostly underdeveloped regional airports.

So it was that SpiceJet launched its first seaplane service in the state of Gujarat in October 2020, linking Ahmedabad – India’s seventh-busiest airport – with Kevadia, some 200 kilometers away. Kevadia is noteworthy as a tourist destination, being home to the new ‘Statue of Unity’ of Former Deputy Prime Minister Patel, the largest statue in the world.

Photo: Gujarat Government

Ajay Singh, chairman and managing director of SpiceJet, explained why seaplane services are so important:

“With the ability to land on a small water body, seaplanes are the perfect flying machines that can effectively connect the remotest parts of India into the mainstream aviation network without the high cost of building airports and runways.”

The service quickly ran into issues

The new service was inaugurated by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who joined the first flight and took the 50-minute ride from Kevadia to the Sabarmati Riverfront in Ahmedabad. But even before he boarded, the service was flying into strong headwinds. It was reported that SpiceJet and its partners didn’t have the necessary environmental clearances, particularly related to the construction of water aerodromes in both cities. And then there were serious issues with the aircraft itself.

Photo: SpiceJet

SpiceJet began the service with a 15-seat de Havilland Twin Otter 300 leased from Maldivian, a carrier that has a long history of using seaplanes to serve the scattered atolls of the Maldives. However, the aircraft (8Q-ISC, msn 321) was manufactured 52 years prior and required frequent maintenance. The result was that SpiceJet’s seaplane flights were regularly suspended for maintenance, and on two occasions within the first four months of operation, the aircraft was flown back to the Maldives for weeks-long service intervals.

Photo: SpiceJet

SpiceJet pulls out, but do opportunities remain?

By April 2021, SpiceJet had made the decision to suspend the seaplane service because it was becoming too difficult to manage. Only 276 flights in total were operated over the course of half a year, carrying a total of 2,192 passengers. The Gujarat state government later admitted that the service had “been terminated due to the high costs of operation”, and despite more than $2 million invested to date in the water aerodromes.

Yet India would seem to have all the ingredients for regional seaplane services:

- Vibrant aviation sector: It is already a commercial aviation powerhouse, currently the third-largest and fastest-growing market in the world.

- Government support: The UDAN program is investing heavily in regional aviation initiatives to extend services to unserved and under-served areas.

- High-growth tourism sector: India’s tourism market is already worth $24 billion, and projected to grow rapidly at a rate of 9.6% over the next four years.

- Conducive Geography: Perhaps most importantly, India is a country of long coastlines, plentiful waterways, and many islands. The perfect topography for the same sort of successful seaplane operations that can be seen with Trans Maldivian Airways and Maldivian in the Maldives, Kenmore Air in Seattle, Canadian operator Harbor Air, or the services operating out of Lake Hood, Alaska, the world’s busiest seaplane base.

A second hope for seaplane service

The Gujarat government clearly agrees, and later in 2021 it put out a tender to replace the short-lived SpiceJet service. By February 2022, it was reported that out of three finalists, the tender had been awarded to Maritime Energy Heli Air Services (MEHAIR) to resume seaplane operations on the Ahmedabad- Kevadia route.

Announcing the agreement, Captain Ajay Chauhan, director of civil aviation for Gujarat state explained why things would be better on this second go-around:

“The aircraft used for relaunch will be Indian registered, and is amphibious unlike the earlier one. The previous operator had to go to Maldives for maintenance or repair purposes, but now it can be done at the MRO facility in Ahmedabad.”

MEHAIR is also far more experienced with seaplane operations compared to SpiceJet, having served the Andaman and Nicobar Islands for over a decade with a fleet of Cessna Grand Caravans. It is also a company that is clearly not shy of making adventurous investments. It plans to retrofit hydroelectric engines to its Grand Caravan fleet, and last year it signed an order with Switzerland-based Jekta for 50 electrically powered seaplanes.

Photo: Jekta

An uncertain future

At face value, MEHAIR appeared to be the well-funded, experienced hand needed to re-launch seaplane services. But 2022 passed by, and no new service was launched. Somewhere along the way the plans must have broken down, because in May 2023, a new tender was launched for the service. But as recently as February 2024, the Gujarat government reported that there had been no takers for the new service.

It is clear that despite government investment and the strength of India’s aviation sector, it is proving far more difficult than expected for seaplane services to get off the ground. But the fundamentals supporting seaplane services to remote parts of the country remain, so it is surely just a matter of time before the enterprising investors are found that can get the business model right.

Have you ever flown on a seaplane? What do you think is required for successful seaplane services in India? Share your thoughts and experiences in the comments.