Summary

- British Airtours Flight 328 ended in a tragic fire, causing 55 fatalities – primarily due to toxic smoke inhalation.

- The AAIB investigation revealed that poor engine repair caused an engine failure leading to the accident.

- Changes post-accident improved safety, introducing new cabin safety measures and proper exit briefings for passengers.

It was August 22nd, 1985, and the start of another busy summer day at Manchester Airport (MAN) in the north of England. Passengers were excited about boarding their annual flight to the sun for a week or two – families, couples, and friends queued up at the British Airtours check-in desks, handing over their bags for their early morning flight to Corfu, one of the larger Greek Islands.

Of the 131 passengers boarding that flight, 55 of them (along with two crew) would not survive beyond the airport boundary. British Airtours Flight 28M (officially known as Flight 328) caught fire on takeoff, resulting in 55 fatalities. Let’s look at one of the most horrific events in British aviation history.

Just a routine holiday flight

- Date: August 22, 1985

- Aircraft type: Boeing 737-236 Advanced

- Aircraft name: River Orrin (formerly Goldfinch)

- Operator: British Airtours

- IATA flight No.: KT328

- ICAO flight No.: BKT28M

- Call sign: BEATOURS 28 MIKE

- Registration: G-BGJL

- Flight origin: Manchester Airport

- Destination: Corfu International Airport

British Airtours was the charter arm of British Airways, which operated both long and short-haul flights for its sister company, British Airways Holidays, alongside other inclusive tour operators. British Airtours flight 328 (callsign ‘Beatours 28M’) was to be operated by a Boeing 737-200 that day, registered G-BGJL and named ‘River Orrin’.

At 06:08, with all 131 passengers and baggage onboard and its two engines started, the aircraft – crewed by two pilots and four cabin crew – was cleared to taxi towards Manchester Airport’s then-single Runway 24 for departure.

At 06:12, the aircraft was lined up at the end of the runway and subsequently cleared for take-off. Back in the briefing room, the flight crew had decided that the first officer, Brian Love (aged 52), would be the handling pilot for the Manchester to Corfu sector that day.

Rejected take-off

|

Occupants |

137 |

|---|---|

|

Passengers |

131 |

|

Crew |

6 |

|

Fatalities |

55 (53 passengers, 2 crew) |

|

Injuries |

15 (serious injuries) |

|

Survivors |

82 |

The Aviation Safety Network highlights that as the 737 accelerated down the runway, the captain, Peter Terrington (aged 39), made the routine ’80 knots’ speed check call. However, just twelve seconds later, with the aircraft fast approaching ‘V1’, the speed beyond which the plane is committed to flying regardless of what might occur, a massive ‘thump’ was audible by all those onboard.

Following standard procedures and fearing that a tire had burst, or a bird strike had occurred, the captain immediately called ‘stop,’ rejecting the take-off. The throttles were closed, and reverse thrust was selected to slow the aircraft. The maximum recorded speed during the take-off run was 126 knots.

Forty-five seconds after the aircraft had commenced its take-off run and nine seconds after the ‘thump’ was heard, the airplane decelerated over 85 knots. The fire bells sounded for engine one in the cockpit, and the captain relayed this to air traffic control.

Related

Which Aircraft Types Did British Airtours Fly?

BEA created British Airtours so that they could compete with tour operators.

Evacuation ordered

An evacuation was ordered 25 seconds after the ‘thump’ and 20 seconds before the aircraft fully stopped. The air traffic controllers on duty, already seeing smoke pouring from the aircraft, responded by informing them that the airport fire service (AFS) was being dispatched to the plane. However, the fire service had already initiated a response, witnessing the aircraft alight for themselves. Having taken guidance advice from the tower controllers, the flight crew ordered passengers to leave via the right, or starboard, side of the plane once it came to a halt.

This decision, in theory, should have kept passengers away from the left (port) side, where engine number one was already engulfed on fire. The aircraft turned off the active runway, vacating onto a short taxiway known as ‘link D.’ The plane finally came to a complete stop facing northwest, fortuitously in a location close to the airport fire station.

Once the aircraft stopped, the flight crew carried out the number one engine fire drill, and the number two engine was shut down. Once this was complete, the passenger evacuation was carried out, with fire spreading rapidly forward on the aircraft’s left side. Both flight crew members escaped through the sliding window on the right-hand side of the cockpit.

Inferno engulfs the rear fuselage

Pratt & Whitney JT8D engine

- Type: Dual-spool, low-bypass turbofan

- Length: 154 in (390 cm)

- Diameter: 49.2 in (125 cm) fan

- Compressor: Axial flow, 1-stage fan, 6-stage LP, 7-stage HP

- Combustor: Nine can-annular (“cannular”) chambers

- Turbine: 1 stage HP, 3 stage LP

- Maximum thrust: 21,000 lbf (93 kN)

- Fuel consumption: 19% reduction over JT3D

- Specific fuel consumption: 22.661 g/(kN⋅s) (0.8000 lb/(lbf⋅h))

An intense fire developed rapidly across the plane’s left side as a light wind of 7–8 mph (11–13 km/h) from the west fanned the fire and dense smoke directly onto and into the rear of the passenger cabin. Cabin windows began to crack, and the fuselage skin buckled as the intense heat entered. Upon reaching a stop, passengers attempted to move the aircraft towards the exits.

In the chaotic series of events that followed, the purser on the flight attempted to open the front right door (R1), but the escape slide container jammed on the doorframe, preventing the slide from deploying and stopping the door.

The purser crossed to the left front door and opened it (contrary to the captain’s instructions). Twenty-five seconds had now passed since the aircraft had stopped. He then returned to the right-hand door and freed it. This was now 85 seconds after the plane had halted.

Passengers hampered in the evacuation

In the meantime, passengers had also managed to open the right-hand overwing exit. Additionally, the right rear door (R2) had also been opened, but due to the density of the smoke and the intense heat at the rear of the chain, no one chose to escape through this exit. The subsequent inquiry found that 17 surviving passengers escaped through the L1 door, 34 through R1, and 27 through the overwing exit. However, serious difficulties were encountered around the overwing exits.

The left overwing exit was blocked by smoke and flames, while the passengers seated at the right overwing exit did not fully understand how to operate the hatch. At the time of the accident, there was no requirement that exit-row passengers be briefed on how and when to open the overwing exit.

Once the exit hatch, which weighed 22 kg (48 lb), was eventually released, it fell inwards, trapping the passenger seated next to it. Although two passengers put the hatch on a seat in the next back row, the restricted seat pitch and having the armrests down for take-off severely inhibited the egress of passengers through this exit.

Passengers towards the plane’s rear panicked as smoke and flames poured into the cabin, which induced something of a stampede to escape the burning aircraft. There were 82 survivors of the accident, while 55 died as a result.

It was found that a combination of toxic smoke and fire was the cause of death for 53 passengers and two cabin crew, 48 of them purely from smoke inhalation. Seventy-eight passengers and four crew escaped, with 15 people sustaining severe injuries.

Causation

Upon subsequent inquiry, the UK’s Air Accident Investigation Branch (AAIB) found that the cause of the accident was an uncontained failure of the left engine, initiated by a failure of the combustor can, which had been incorrectly repaired following a recent inspection.

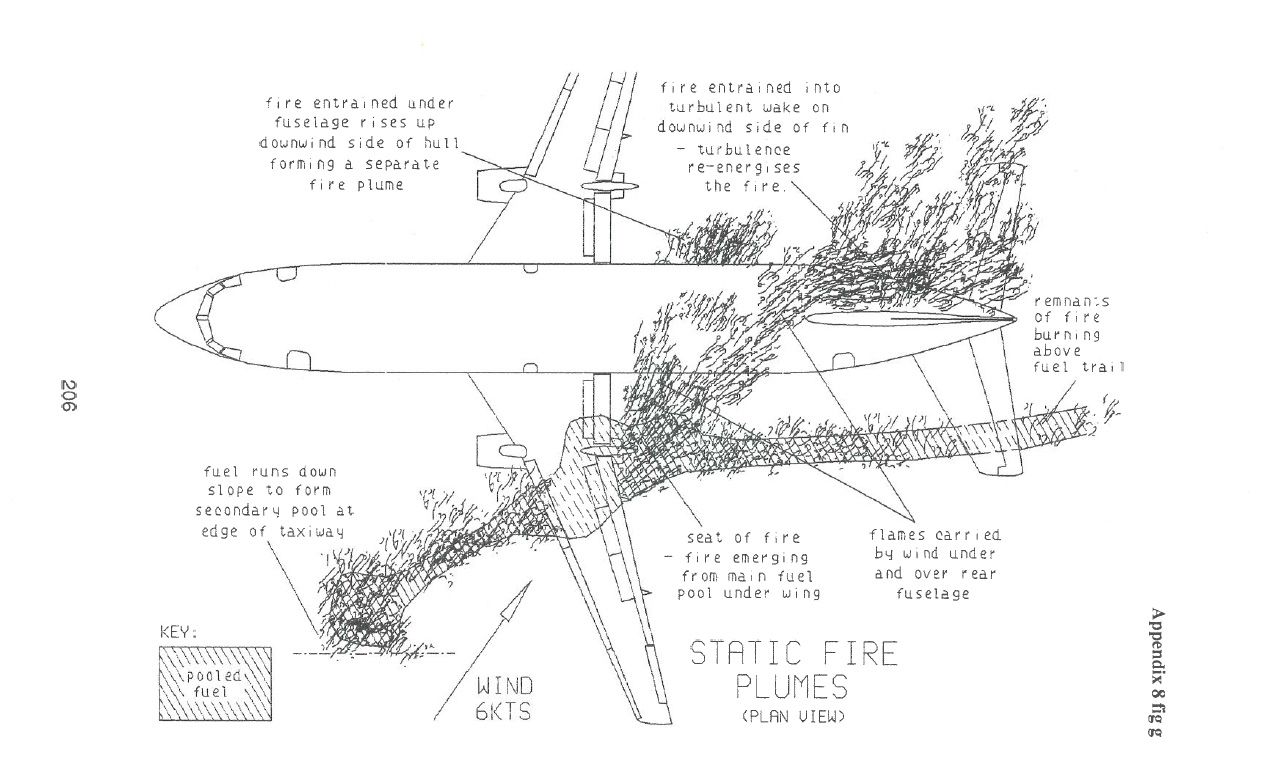

Sections of the turbine disc were ejected forcibly from the engine, struck, and fractured an underwing fuel tank access panel. Fuel poured from this point of fracture and immediately ignited. The resulting fire developed primarily because of the adverse orientation of the parked aircraft relative to the wind, even though the wind was light.

The primary cause of the fatalities was rapid incapacitation due to the inhalation of the dense toxic/irritant smoke atmosphere within the cabin, aggravated by evacuation delays caused by a forward right door malfunction and restricted access to the exits.

Related

The British Airtours Disaster: A Cabin Crew Perspective

Determination and bravery saved lives.

Findings of the inquiry

In summing up its findings following the inquiry into the accident, the AAIB stated that the following factors aggravated the loss of life onboard Flight 328:

- The vulnerability of the wing tank access panels to impact from objects

- The lack of adequate provision for fire fighting inside the aircraft cabin

- The vulnerability of the aircraft skin to external heat and fire

- The highly toxic nature of the emissions from the burning interior materials

- The final orientation of the aircraft gave the direction of the wind at the time of the accident

Lessons learned from this tragic event

There were many lessons to be learned by the aviation industry following this. As a result of the appalling loss of life, changes to passenger aviation were introduced, the impacts of which remain in evidence today.

The spacing of seating adjacent to emergency exits and overwing exits was increased, with briefings for those passengers seated in these rows regarding how to use the exits being made a requirement. Additional fire extinguishers are also to be provided in the passenger cabin.

Emergency floor-mounted lighting was introduced, and new rules regarding the use of fire-resistant seat coverings, wall panels, and ceiling panels were brought in. Finally, passengers must be reminded that their nearest exits may be behind them during the pre-takeoff safety briefing.

Although research into the introduction of smoke hoods for passengers followed the accident, the research results were never enacted by airlines, given the contradictory findings of this research. It was found that while hoods could save lives, the time it takes passengers to find and put them on could take valuable seconds of critical time, particularly in a smoke-filled cabin.

Nonetheless, the accident involving British Airtours Flight 328 almost four decades ago has been described as a defining moment in the history of civil aviation following the introduction of these various new safety measures.

Related

Did You Know British Airways Used To Fly Air New Zealand McDonnell Douglas DC-10s To The US?

A look back in time at how British Airways pilots and cabin crew flew Air New Zealand DC-10s between the UK and the US.

What do you make of the events that led to the British Airtours incident and that followed after the incident? Share your views in the comments section.