Summary

- In the late 1960s, the UK government pushed for V/STOL innovation to address airport congestion and noise pollution.

- This led Hawker Siddeley to develop the HS.141, a 100-seat V/STOL aircraft with a range of 500 miles and a cruising speed of 600 mph.

- The project ultimately failed due to the global recession, the collapse of Rolls-Royce, and the high cost of infrastructure upgrades for V/STOL aircraft.

In the late 1960s, the usage of jet aircraft for commercial aviation was increasing substantially, but there was a growing concern about crowded airports and increased noise pollution. These concerns were particularly acute in Britain, which led to increased interest in the potential use of vertical and/or short take-off and landing (V/STOL) aircraft for regional flights.

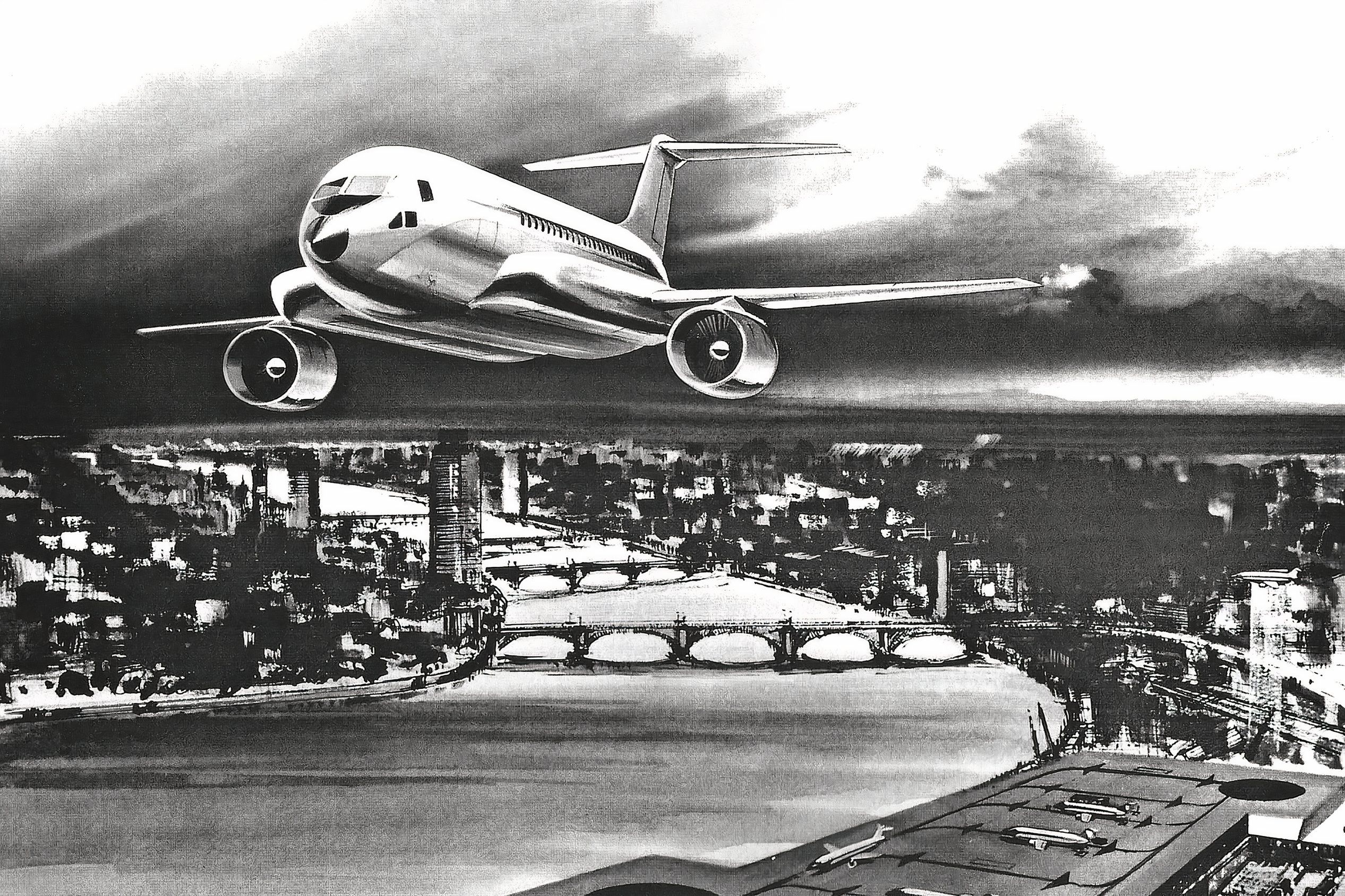

Photo: BAE Systems

As a major British manufacturer, Hawker Siddeley was ideally positioned to capitalize on this momentum. After all, it had successfully launched the Hawker Siddeley HS-121 Trident earlier in the decade, proving its abilities with regional airliners. It was about to revolutionize military aviation with the Hawker Siddeley Harrier GR.1. It only seemed logical that it should combine this experience to create the world’s first V/STOL commercial airliner.

Related

The Story Of The Hawker Siddeley Trident

The impetus came from the UK government

The UK government was pushing for V/STOL innovation at the time. In 1967, the Transport Aircraft Requirements Committee (TARC) circulated the need for an inter-city V/STOL aircraft, promising significant government support for the project. The Ministries of Transport and Technology and the National Research Development Corporation all got on board, seeing V/STOL as a means to preserve space at current airports (and not have to build new ones) as well as minimize noise levels.

Photo: BAE Systems

By 1969, just as the first Hawker Siddeley Harriers were starting flying with the RAF, the government had issued its guidelines to industry on transport requirements for the 1980s. It called for a commercial 100-seat V/STOL passenger aircraft with a range of at least 450 miles. This effectively kicked off a design competition between the UK’s three main airframe contractors: Hawker Siddeley, the British Aircraft Corporation (BAC), and Westland.

The three different design concepts

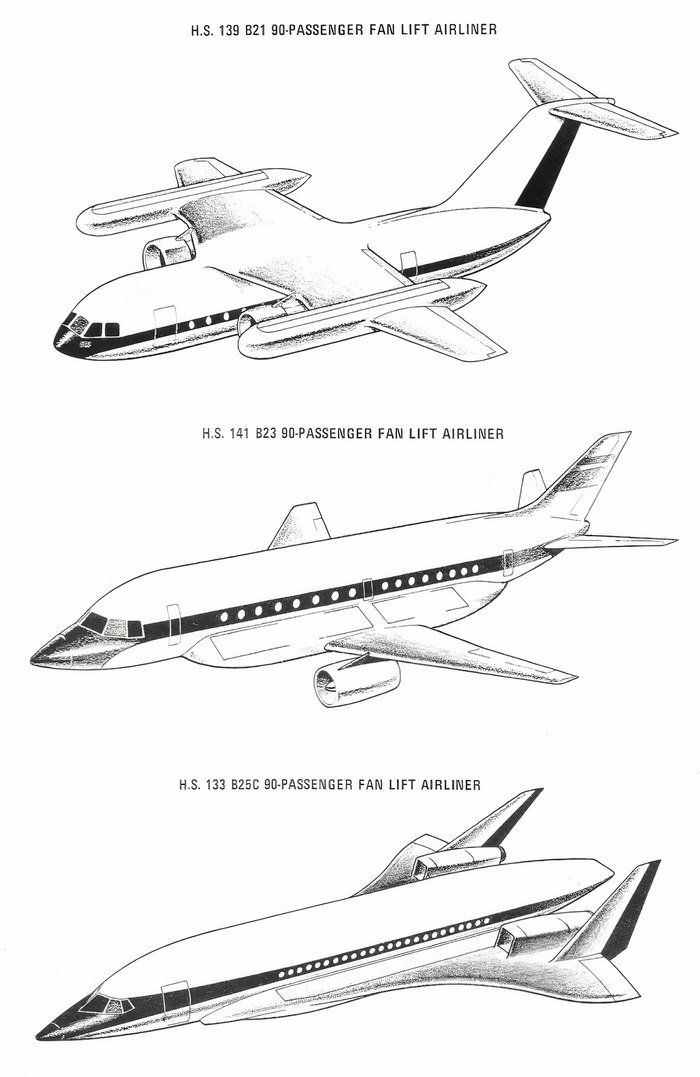

Hawker Siddeley had already invested a lot of time and money in V/STOL design over the decade and so was rapidly able to respond with three different design options (see image below):

- HS.139 (top): A high-wing design that had the lift systems attached in wing-mounted pods, each containing a battery of lift fan engines. It was rejected as aerodynamically inferior, adding extra weight and drag and reducing the projected cruising speed.

- HS.133 (bottom): A delta-winged design that was the most visually appealing and revolutionary, which at the outset was the favored approach. However, it was ultimately also rejected as carrying too much technical risk.

- HS.141 (middle): A low-wing design with lift systems placed within the sponsons integrated with the wing and fuselage. It was ultimately the chosen design, being more conventional, aerodynamically clean, and allowing for a lighter, faster aircraft.

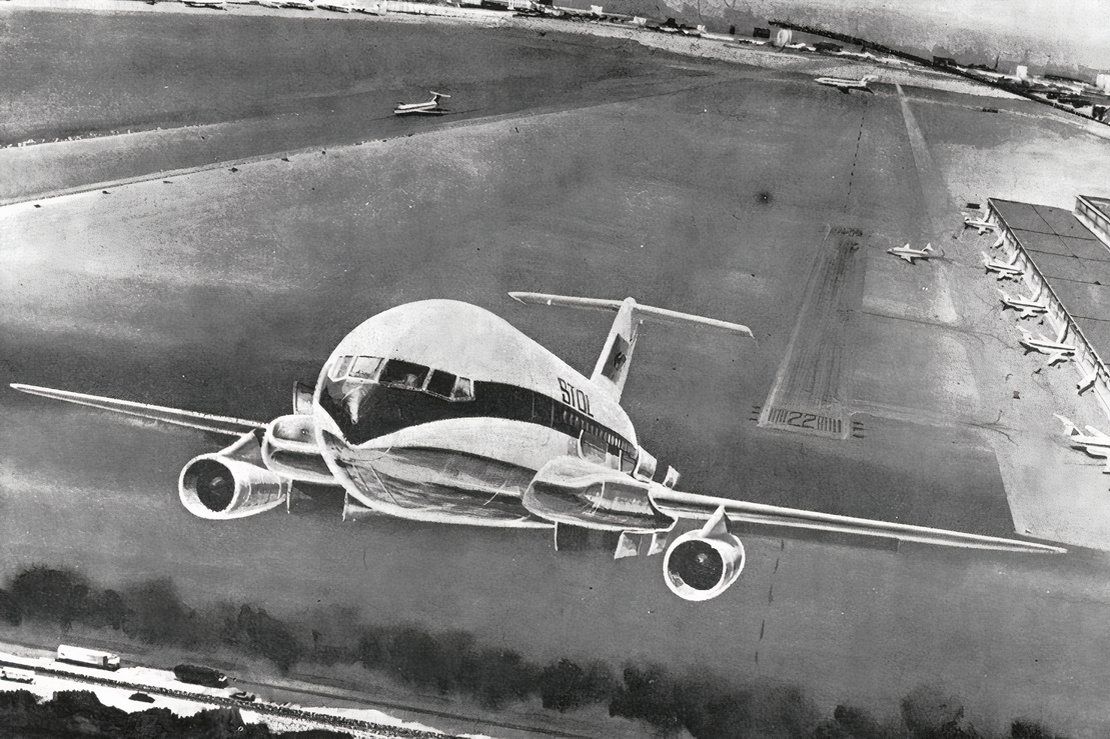

Photo: BAE Systems

Hawker Siddeley threw its full weight behind the HS.141 design and, over the next three years, invested a considerable amount of time and finance in its development. The company’s deputy managing director, Sir Harry Broadhurst, made it clear how committed they were to the project:

“VTOL and STOL are the only things in technology left where we have a considerable lead and we have spent a lot of money. This will come to full fruition in about 1980, but what we need now is a vehicle to put the engines in and with which to do the systems and noise work.”

Developing the HS.141

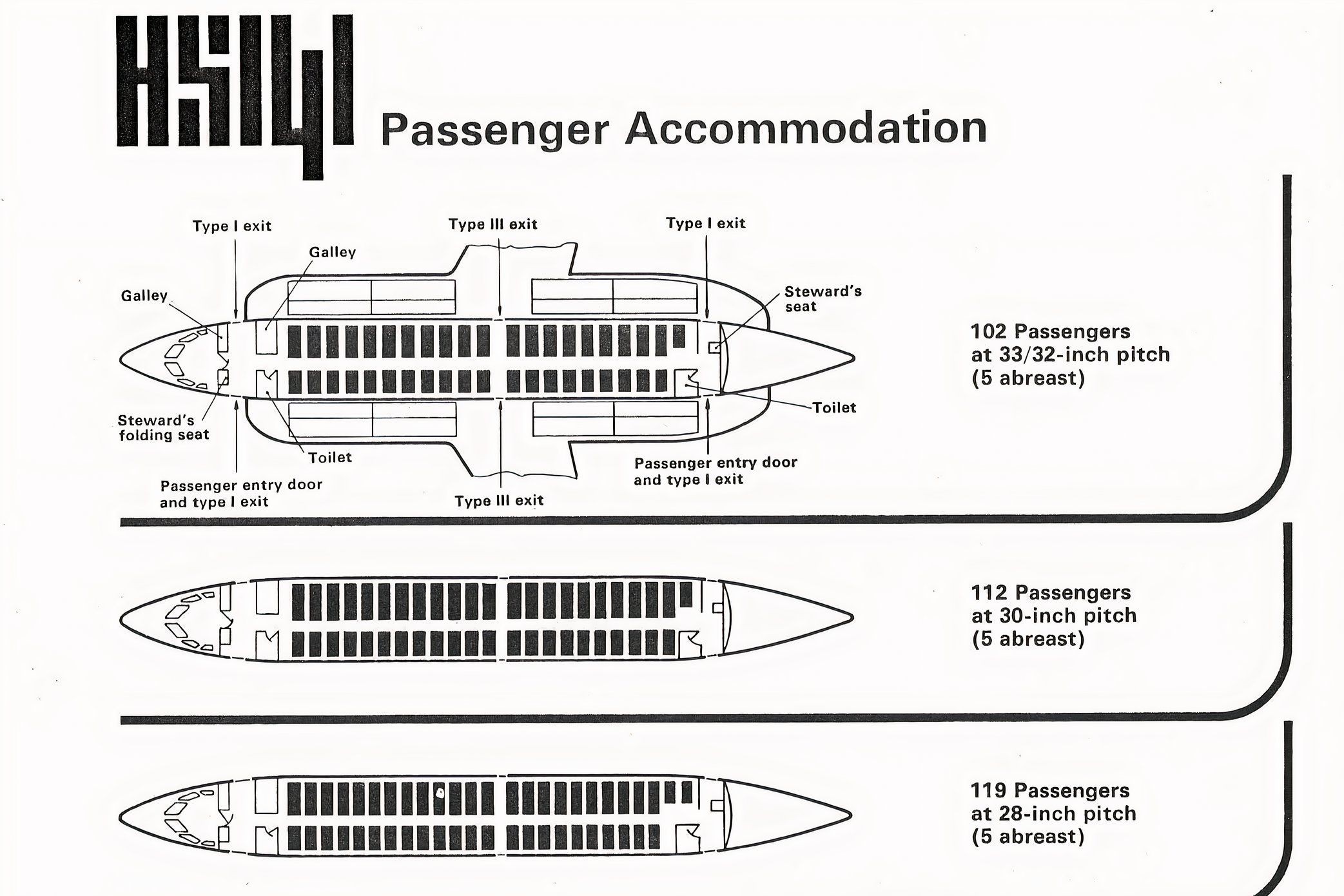

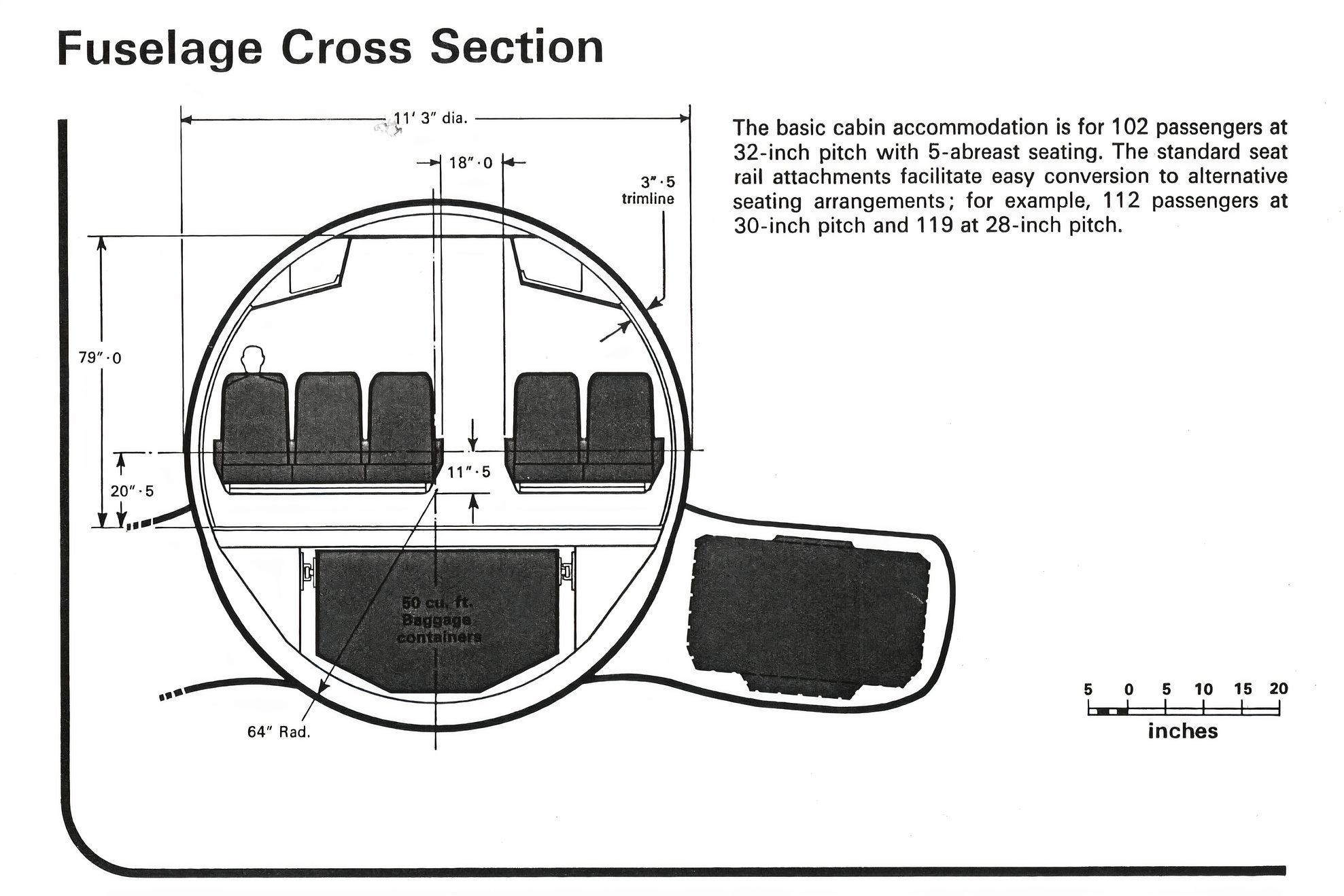

Presentations were made to various government agencies in the early 1970s. The HS.141 was pitched as an aircraft able to accommodate 102-119 passengers in five-abreast seating. Powered by 16 Rolls-Royce RB202 lift fans (eight on each side) and two Rolls-Royce RB220 propulsion turbofans, it would have a range of 500 miles and a cruise speed of 600 mph. Most importantly, it would limit maximum take-off/landing noise to 90 decibels at a radius of 1,500ft. A conventional airliner at the time had a 90-decibel noise footprint over some 30 square miles, and by comparison, the HS.141 was a quarter of a square mile.

Photo: BAE Systems

Crucial to the design of the aircraft was the RB202 lift fan engine of 10,000-20,000lb thrust. Rolls-Royce was developing it for multiple projects that included the Dornier Do 231 and Fokker VC180P as well as the HS.141. The RB202 was designed with low noise as the primary objective and incorporated a three-stage low-pressure turbine. Rolls-Royce expected to have the engine available from 1976.

Photo: BAE Systems

How it would have worked

The operation of the HS.141 promised to be truly revolutionary. Its take-off involved using maximum lift thrust until it reached 250 ft, dropping to 83% thrust for lower noise levels for the remainder of the climb. Forward transition would be initiated at 1,000 ft by tilting the fan engines, and then continue to accelerate with its cruise engines. Once it reached an air speed of 168 knots, about a minute after leaving the launch pad, the lift engines would be shut down and the exhaust and inlet doors closed.

Photo: BAE Systems

For landing, the lift fans would be started at 2,000 ft when about four miles from the destination. The deceleration transition would then begin about half a mile out, at an altitude of about 1,000ft, until the aircraft was overhead the landing pad. The let-down procedure would start at about 35 ft/s and reduce to 10 ft/s by the time it was 100 ft above the pad. The total time for transition and landing was estimated at about 2 minutes.

Photo: BAE Systems

The plans never came to fruition

As exciting as that sort of flight sequence sounds, the development of HS.141 sadly never became a reality. While Hawker Siddeley was still referencing it in presentations as late as 1972, the world was changing and the demand for V/STOL aircraft was evaporating for numerous reasons:

- Global recession: As the fuel crisis and resulting recession hit, there was no longer available government funding to support the development of the aircraft.

- Cost of infrastructure: V/STOL aircraft also necessitated major upgrades to existing airports, an investment the UK government simply couldn’t afford.

- Engine failure: The collapse of Rolls-Royce had also put an end to the development of the RB202 engine, and Hawker Siddeley didn’t have any viable alternatives.

- More profitable ventures: Faced with all this, Hawker Siddeley made the prudent decision to develop more conventional aircraft, which ultimately resulted in the BAe 146

Related

Quirky Quadjet: 40 Years Of The British Aerospace 146

Yet, there might still be a future for V/STOL passenger aircraft. Airbus has shared its plans for an eVTOL aircraft, with an intended first flight before the end of the year. Embraer is working in partnership with Uber to develop eVTOL aircraft for air taxi operations. And Sirius Aviation even has plans for a hydrogen-powered VTOL aircraft which it hopes to certify by 2026. So there is still hope that you might experience the thrill of a V/STOL commercial flight in the not too distant future.

Photo: Sirius Aviation

What are your thoughts on V/STOL commercial aircraft? Would you be comfortable flying in one? What will it take to make a V/STOL aircraft commercially successful? Share your thoughts and experiences in the comments.