Summary

- Airspace is classified based on factors including air traffic volume, airport complexity, and operational needs.

- Each airspace class has specific requirements for pilots, including communication, equipment, and weather minimums.

- Understanding airspace classifications is essential for safe and efficient flight operations.

Airspace classification is a critical component of aviation safety and efficiency. The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) has established a system to categorize airspace based on factors like air traffic volume, airport complexity, and operational requirements. This structure ensures the safe and orderly flow of air traffic.

This guide delves into the intricacies of airspace classes, from the high-altitude reaches of Class A to the uncharted territories of Class G. These airspaces will, for the most part, be referred to by their phonetic alphabet name. We’ll explore the characteristics, requirements, and visual representations of each class, providing a clear understanding of the airspace you’ll encounter during flight.

The information and sectional charts provided are subject to change and should not be used for flight training purposes. For the latest details, please refer to the most recent official FAA publications.

1

Class Alpha

Not for airports

The first airspace is Class Alpha. It spans all 48 contiguous states and Alaska, including 12 miles offshore, from 18,000 to 60,000 feet above sea level, but never depicted on maps. Remember, “A for Altitude.” Before entering the airspace, a few things must be sorted out. Fundamentally, the aircraft must be certified to climb to that altitude and have either an oxygen supply or pressurization capabilities.

All airliners and private jets fly in that altitude range and thus are pressurized. Next, the pilot must have an instrument rating; all Class Alpha airspace flights must be on an instrument flight plan unless otherwise specified. Ergo, an instrument flight plan must be filed before the flight. The speed limit in Class Alpha airspace is Mach 1, or the speed of sound.

Related

What Happens If Unpressurized Aircraft Fly Excessively High?

There are severe consequences for occupants of unpressurized aircraft flying excessively high without supplementary oxygen available.

2

Class Bravo

300,000+ total ops with 5 million+ passengers

Class Bravo airspace is the first on this list designated for an airport. Think “B for Big. Big jets, big size.” The following is a short list of the 37 Bravo Airspaces:

- Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport (ATL/KATL)

- Boston Logan International Airport (BOS/KBOS)

- Chicago O’Hare International Airport (ORD/KORD)

- Las Vegas Harry Ried International Airport (LAS/KLAS)

- Los Angeles International Airport (LAX/KLAX)

- San Francisco International Airport (SFO/KSFO)

- Phoenix Skyharbor International Airport (PHX/KPHX)

- Orlando International Airport (MCO/KMCO)

- Miami International Airport (MIA/KMIA)

- Honolulu International Airport (HNL/PHNL)

Because it has three shelves that expand with altitude, Bravo Airspace is typically called an upside-down wedding cake. The innermost shelf spans ten nautical miles around the airfield from the surface to the ceiling of 10,000 feet; the middle shelf spans 20 nautical miles from the airport but starts at 3000 feet; the outermost shelf spans 30 nautical miles from the airport and begins at 5000 or 6000 feet and goes to the ceiling. As a result of its size, some Class Bravo airspaces encompass multiple Bravo airports; JFK International, Newark Liberty International, and LaGuardia Airports all share one Bravo Airspace.

Some airports with other airspace classes can sit under Class Bravo airspace. Orlando-Sanford International Airport (SFB) has Class Charlie airspace despite being underneath the Class Bravo of Orlando International (MCO).

Map: Skyvector.com

Bravo airspace can be identified on a sectional map by the blue solid lines around an airport, as depicted on the map above. The thin red line encompassing it is the Mode C veil, meaning all aircraft must be equipped with a Mode C transponder before entering the area. Air traffic must also slow to 250 knots below 10,000 feet and 200 knots inside the Bravo. Pilots must obtain clearance from an Approach controller before entering Class Bravo airspace. This clearance will sound like “N172SP, cleared to the Detroit Class B airspace via Adrian, expect 5000, squawk 0214.” One pilot infamously entered the Las Vegas Bravo airspace without clearance and disregarded the controller’s orders to exit. The uncleared pilot posed a threat to the pilot and other aircraft in the air nearby and on the ground. At least a private pilot’s license or a student pilot certificate with an instructor’s endorsement is also necessary to enter a Bravo Airspace.

3

Class Charlie

Primary airport: 75,000 instrument ops, 100,000 combined instrument ops with secondary airport, 250,000 passengers.

Class Charlie airspace is the next airspace for an airport. Class Charlie is the airspace at medium-sized airports; think “C for crowded.” The following is a short list of the 122 Charlie Airspaces:

- Louisville Muhammad Ali International Airport (SDF/KSDF)

- Albany International Airport (ALB/KALB)

- Fresno Yosemite International Airport (FAT/KFAT)

- Omaha Eppley Airfield (OMA/KOMA)

- Chicago Midway International Airport (MDW/KMDW)

- Oakland International Airport (OAK/KOAK)

- Windsor Locks Bradley International Airport (BDL/KBDL)

- Indianapolis International Airport (IND/KIND)

- South Bend Regional Airport (SBN/KSBN)

- Maui Kahului Airport (OGG/PHOG)

Map: Skyvector.com

Charlie airspace can be identified on a sectional map by two thick red lines around an airport, as depicted on the map above. Clearances are also required to enter Class Charlie airspace, although this can be obtained from a Tower or approach controller. This clearance will sound something like, “N172SP, Islip Approach, radar contact, squawk 1200. Maintain 3,000; contact Islip Tower on 119.3.” Since they are typically less busy, Class Charlie airports are the largest at which student pilots are allowed to fly without an extra endorsement.

A fun tidbit of information is that Daytona Beach International Airport meets the criteria to be a Class Bravo airspace because there are so many movements from the flight schools. However, due to the flight schools on the field, it must remain a Class Charlie airspace.

Photo: Noah Cooperman | Simple Flying

4

Class Delta

No inherent traffic or volume requirements.

Class Delta airspace is the last airspace for a controlled airport; think “D for dialogue” when talking to the tower instead of an approach controller. The following is a short list of the more than 428 Delta airspaces:

- Westchester County Airport (HPN/KHPN)

- Guam International Airport (GUM/PGUM)

- Van Nuys Airport (VNY/KVNY)

- Prescott Municipal Airport (PRC/KPRC)

- Dover Air Force Base (DOV/KDOV)

- New Haven Tweed Airport (HVN/KHVN)

- Charles M. Schulz–Sonoma County Airport (STS/KSTS)

- Carbondale Murphysboro Southern Illinois Airport (MDH/KMDH)

- Purdue University Airport (LAF/KLAF)

- Everett Paine Field (PAE/KPAE)

Photo: Noah Cooperman | Simple Flying

The clearance into Class Delta airspace will likely sound different from the previous two. Rather than explicitly telling the pilot to enter the airspace, the controller will likely fulfill the pilot’s request. For example, permission might just be the controller telling the pilot to follow traffic inbound and land. “N172SP, Waterbury tower, traffic in sight, cleared to land runway 18.” Class Delta airports are the least busy, so it’s most common to find student pilots in the area.

Map: Skyvector.com

Delta airspaces don’t have shelves; they only span from the surface to 2500 feet and stretch five miles outward. The airspaces are depicted on maps with blue dotted lines encompassing the airport. Please see the next section about the dashed red line.

Unlike Class B and C airports, the air traffic control towers at Class D airports are not required to be open 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. The air traffic control tower at East Hampton Airport on Long Island, New York, is only active from Memorial Day until Labor Day each year. Whenever the air traffic control tower is closed, the airspace is considered Class Echo airspace, and pilots are responsible for communicating with each other.

Related

Hub to the Hamptons: All About East Hampton Airport

East Hampton Airport: A historic aviation hub with top-notch services, sustainable practices, and charter and fractional ownership operations.

5

Class Echo

Controlled airspace

This is where things get complicated. Class E airspace is controlled airspace that typically extends from 11,200 feet above ground level (AGL) up to 18,000 feet Mean Sea Level (MSL). However, it can also begin at lower altitudes, such as 700 feet AGL, or even at the surface. Remember, “E is for everything else.”

Pilots operating in Class E airspace must maintain two-way radio communication with air traffic control (ATC), though this is often advisory rather than mandatory. While not required, a transponder is recommended.

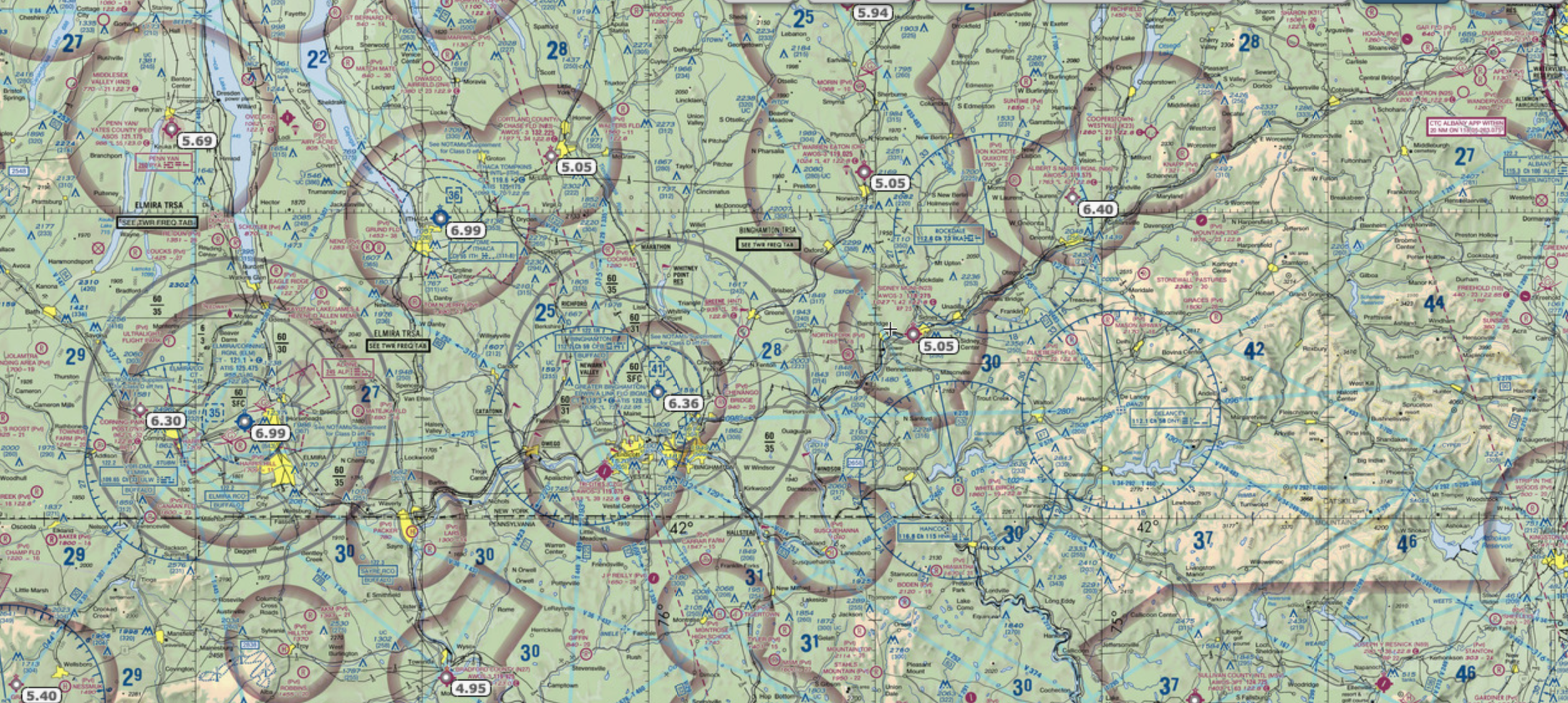

Class E airspace is depicted on sectional charts in three ways. A dashed magenta line indicates that Class E airspace starts at the surface, such as around an airport. This type of airspace provides extra protection for aircraft arriving at airports without control towers on cloudy days. Elmira Corning Regional Airport (ELM/KELM) is depicted with this extension.

Map: Skyvector.com

A magenta-shaded area indicates that Class E airspace starts at 700 ft AGL. These transition areas are often found near airports and are usually surrounded by Class E airspace. The map below depicts several such examples of airfields.

Map: Skyvector.com

Lastly, if there’s no magenta line or circle, or if an airfield is outside the circle, Class E airspace starts at 1,200 ft AGL.

There is no Class Foxtrot airspace in the United States.

6

Class Golf

Uncontrolled airspace

Class G airspace is uncontrolled, meaning there is no air traffic control (ATC) service. It typically extends from the surface up to 1,200 feet AGL but can be higher in some areas. Remember “G means ‘go for it'”; there are few rules, and you’re flying mostly in the “wild west” of airspace.

Pilots operating in Class G airspace are solely responsible for seeing and avoiding other aircraft. While radio communication is not required, it is highly recommended for safety. Class G airspace is generally depicted on sectional charts by a faded blue boundary line or the absence of any shaded airspace.

Small, rural airports, like those found in many parts of the country, are often located entirely within Class G airspace. Confusing, right? Don’t worry, here’s a table that breaks down the information about Echo and Golf airspaces.

|

Feature |

Class E |

Class G |

|

Altitude |

1,200 ft AGL to 18,000 ft MSL (or other designated altitude) |

Surface to 1,200 ft AGL (or higher in some areas) |

|

Control |

Controlled |

Uncontrolled |

|

Weather Minimums (VFR) |

Below 10,000 ft: 3 miles visibility, 500 ft below, 1,000 ft above, 2,000 ft horizontal. Above 10,000 ft: 5 miles visibility, 1,000 ft below, 1,000 ft above, 1 mile horizontal |

1 mile visibility, clear of clouds |

|

Radio Requirements |

Recommended |

Not required, but recommended |

|

Transponder Requirements |

Recommended |

Not required |

|

Separation |

Provided by ATC (pilots also see and avoid) |

See and avoid (pilot responsibility) |

|

Depiction |

Dashed magenta line (surface), magenta-shaded area (700 ft AGL), or no magenta (1,200 ft AGL) |

Faded blue boundary line or no shaded area |

A thorough understanding of airspace classifications is paramount for pilots of all experience levels. By comprehending the nuances of each airspace, from the controlled environment of Class A to the open expanses of Class G, aviators can make informed decisions, enhance situational awareness, and ultimately contribute to a safer aviation system. As technology and air traffic continue to evolve, it’s essential to stay updated on airspace changes and regulations to ensure compliance and operational success.