During 2024, not only has the city of Paris been hosting the Olympic and Paralympic Games, but Paris-Charles de Gaulle Airport (CDG) has been celebrating its 50th anniversary. It handled its first flight in March 1974 and has since become one of Europe’s busiest airports in terms of annual passenger numbers. In 2023, the airport saw 67.4 million travelers pass through its terminals and is expecting even more in its 50th anniversary year.

AeroTime looks at the history of the airport – its conception and growth over the past half-century, its iconic and groundbreaking terminal design, and the key events over that period that have earned CDG a place in aviation’s history books, for better and for worse.

Background to CDG Airport

Following the conclusion of the Second World War, France experienced economic recovery on an unprecedented level. As the country clawed its way back from the ravages of war and German occupation, its economy began to boom, with annual growth rates peaking at 5% per annum. Additionally, demand for air travel soared in the post-war years, going on to reach even higher levels once the jet age arrived in the late 1950s.

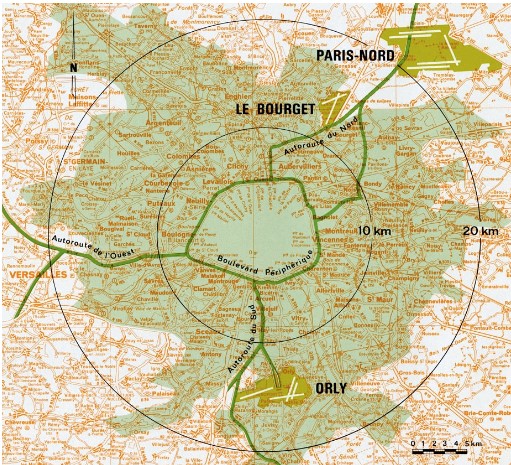

At that time Paris had two main airports – Orly Airport (ORY) to the south of the city and Le Bourget (LBG) to the northeast. Orly (originally called Orly-Villeneuve Airport) opened in 1932, to provide additional capacity for the already constrained Le Bourget. The latter had opened just thirteen years earlier, in 1919, while Orly was used as a German air base during WWII.

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, traffic at both Paris airports continued to rise, but further expansion was restricted by both airports’ relatively urban locations. Additionally, Le Bourget’s capacity was limited to just three million passengers per year. By 1952, this had forced national carrier Air France to relocate its entire operation to Orly, where there was still space for growth and for additional runways to be built.

Yet, with traffic growing at around 15% per year, it soon became clear to the French authorities that even Orly would be unable to sustain the rates of growth being seen in air travel for long. Forecasters predicted that the facility would reach its capacity of 15 million passengers per year by 1975. Therefore, urgent action was needed.

In 1957, the search began for potential sites for an all-new Paris airport, with the strict criterion that any such site should offer considerable room for future expansion. It was hoped that this approach would avoid another overspill situation as previously encountered at Le Bourget and Orly.

Eventually, planners identified a site close to the satellite town of Roissy, 14 miles (22 km) northeast of the French capital which was deemed suitable for the development of the new airport. The land around Roissy was mainly used for agriculture and provided the ‘greenfield’ site required for the new airport, unencumbered by either major settlements or built-up areas.

Construction began in 1964, at which point the project had the working title of Paris-Nord Airport. However, before opening its name was changed, initially to Roissy Airport, before ultimately opening as Roissy-Charles De Gaulle Airport in honor of the former President of France who had died in 1970 and had been instrumental in getting the airport built.

The airport eventually dropped the reference to the nearby town and became known simply as Paris-Charles De Gaulle Airport, the name it still goes by today.

Design and construction

The site at Roissy was advantageous for other reasons. The sparsely populated area meant that there would be little issue with noise pollution from the early jet aircraft, but additionally, accessibility to the location was secured by the opening of a brand new multi-lane autoroute from Paris to Brussels that traversed the area.

When started work on the new airport, its designers knew that it had to be huge and scalable – not only accommodating the rapid rise in air travel at the time. but also to future-proof it for generations to come.

Paris itself saw its population rise exponentially, growing by 25% to around eight million between 1954 and 1968. Those involved also had the foresight to realize that the new airport would have to compete with the likes of London, Frankfurt, and Amsterdam for passengers flying to Europe in the future.

Additionally, the design team, led by Chief Engineer Jacques Block, was mindful that aircraft likely to serve the airport in the future would get larger. While the world had already seen the introduction of the four-engined intercontinental Boeing 707 and Douglas DC-8, larger aircraft were already on the drawing board in the shape of the Lockheed TriStar, the McDonell Douglas DC-10, and ultimately, the Boeing 747.

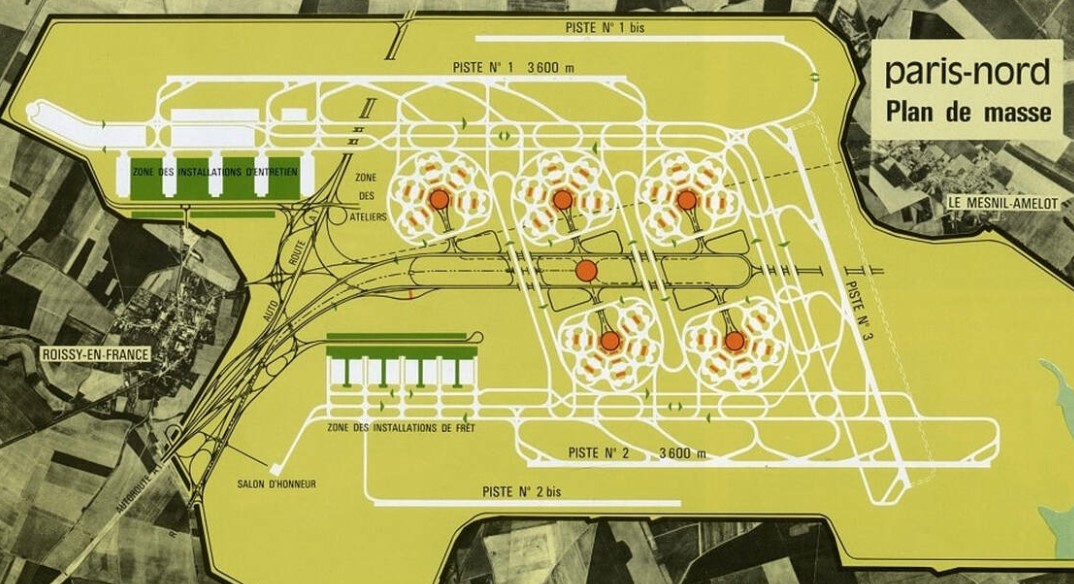

Projections showed that the airport would eventually be required to handle up to 150 landings and take-offs per hour. Given that a single runway can only accommodate around 40 movements per hour, the designers knew they would have to build an airport with at least four runways for the anticipated growth in air traffic.

In 1966, the design team revealed its plans to the public for the first time. The new airport was to be the largest anywhere in the world at the time, covering 12.7 square miles (33 sq. km). The plans allowed for five runways on the site, with a pair of two parallel runways running east to west to the north and south of the main terminal area and with one further runway to allow for crosswinds at the location.

Both the runways and taxiways were designed to accommodate aircraft even larger than the Boeing 747, with the runways being capable of extension beyond their 11,800ft (3,600m) length in the future as necessary.

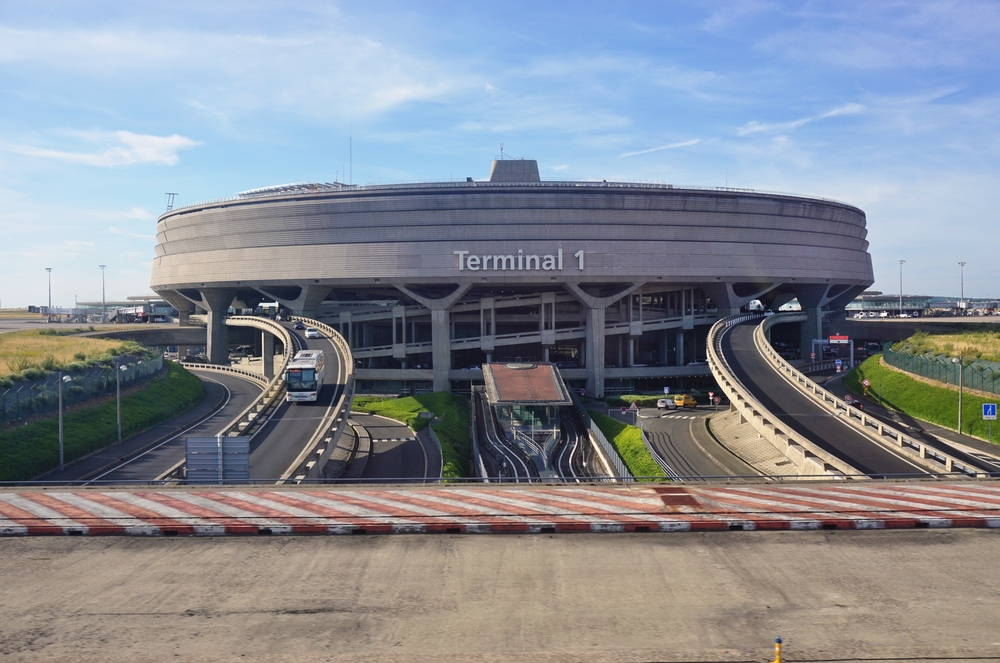

As for the terminal (or ‘aérogare’ in French), the designers were briefed to produce a building concept that was as eye-catching as it was functional. Basing their design on a central circular terminal building with seven outlying wedge-shaped satellite buildings or ‘docks’, the team aimed to maximize passenger flows while also keeping walking and transit times (from car to aircraft) as low as possible, a layout concept already heavily in use in the US.

Each satellite building would be designed to include seven passenger boarding bridges and aircraft stands, four of which could handle Boeing 747s. Additionally, the terminal would see all critical airport functions ‘stacked’ across several stories, with separate levels for car parking and ground transportation, arrivals, departures, and administration offices. Each floor would be connected by a series of ramps, moving walkways, and escalators, again minimizing walking distances.

The airport’s original plans called for five similar terminal buildings, all built in the central area between the runways. The six terminals would be linked to a centralized main building which would feature hotels, restaurants, and shops. It would also be connected via a light rail line to downtown Paris and offer helicopter connections to Orly Airport and other city locations.

However, even before the first terminal had been completed, the plan for multiple circular terminals with their associated satellite buildings had been dropped due to budget constraints, as had the plan for the central building.

However, the original design for the terminal building remained, despite the cutbacks. Officially known as ‘Aérogare 1’, the building was to become the centerpiece of the new airport. Designed by Paul Andreu, an architect employed by the airport’s developer Aéroports De Paris (ADP), the building would be a circular building of concrete construction with a diameter of 630ft (192m) and a height of 173ft (52.7m). Designed in the avant-garde ‘Brutalist’ style of architecture, it was considered to be ‘in vogue’ with current building design trends.

The functions that had been planned to be in the main central building were eventually incorporated into the Aérogare 1 design, meaning that upon completion, the building stood ten stories high.

Grand opening

The new Paris-Charles De Gaulle Airport was officially opened on March 8, 1974, by the then-French Prime Minister Piere Messmer. It had been eight years since construction had first started, with the project costing $275m to complete. It featured just one terminal building and a single runway, and upon opening was allocated its iconic three-letter airport code ‘CDG’ by the International Air Transport Association (IATA).

The airport handled its first commercial flight five days later, on March 13, 1974, in the form of a Boeing 747 operated by US airline, Trans World Airways (TWA) from New York-JFK Airport. This first arrival had only sixty passengers onboard. Meanwhile, the first commercial departure from the new airport involved an Air France Sud-Aviation Caravelle taking off with just a single passenger traveling onboard to enjoy the historic moment.

Other airlines soon began transferring flights to CDG from Orly and Le Bourget (which later closed to airline traffic). Before long, the airport boasted a rollcall of major international carriers such as Pan Am, SAS, Japan Airlines, Air Afrique, Saudia, and British Airways, along with France’s two other mainline carriers of the time, Air Inter and UTA (both of which later merged into Air France).

Over its first year of operations, the airport handled 2.5 million passengers and 131,000 tons of cargo.

Further development

Use of the new airport grew quickly after that first year of operations and by 1976 traffic totals had reached 7.5 million passengers. A second runway opened that same year, and a rail link with central Paris also opened to the public for the first time.

After the early proposal to build a series of round terminals was shelved, the airport pressed ahead with the design and construction of a second terminal (Terminal 2). This building was more of a conventional design and has been expanded several times since to become a series of smaller satellite buildings, each being designated Terminals 2A through to 2G accordingly. Terminal 2 opened in 1981, with Terminal 2B soon following in March 1982.

Terminals 2C and 2D followed, with Terminal 2E opening in 2003 as a dedicated terminal facility for Air France and its SkyTeam alliance partner airlines. Today, the entire Terminal 2 remains in this configuration, with walkways and a light-rail transit (CDGVAL) connecting the individual satellite buildings.

Terminal 3 was opened in 1990 to handle charter flights and was expanded further in 2003. Construction of an additional fourth CDG terminal was considered in 2020, but these plans were later shelved because of the global downturn in traffic following the COVID-19 pandemic.

CDG in the news

As with any major international airport, CDG has had its time in the spotlight for positive and negative reasons over its first 50 years.

The early plans for the airport incorporated designs for a revolutionary mode of transport dubbed the ‘Aerotrain’. This was to be a single-carriage rail-mounted hovertrain that would connect the airport with the city of Paris.

Uniquely, the Aerotrain was to be propelled by a single Pratt & Whitney JT8D jet engine mounted on the roof of the vehicle, as used on Boeing 727s and 737s at the time. However, although two prototypes were built and tested using a turboprop engine, the concept was never developed further, and the project was dropped in 1974.

It also became apparent soon after its opening that the new airport was prone to fog. To combat this issue, the airport devised a revolutionary new method of fog dispersal using a series of Mistral fighter jet engines dispersed along the threshold and touchdown zones of one of the runways.

The concept used the heat produced by the engines to vaporize the fog to assist landing aircraft in poor visibility conditions. However, the enormous consumption of costly jet fuel soon put a stop to the scheme.

In 1976, CDG became just one of just two airports worldwide to act as a base for the only supersonic airliner in service, the Anglo-French Concorde. On January 21, 1976, at 1140, the first two such aircraft to enter commercial service took off simultaneously from London-Heathrow and CDG. A British Airways Concorde departed London for New York, while the first Air France example set off for Rio de Janeiro.

Concorde became a regular sight at CDG over the years and was used on regular Air France transatlantic supersonic services to New York-JFK.

However, on July 25, 2000, an Air France Concorde caught fire on take-off from CDG while setting off on a special round-the-world charter flight carrying US tourists. The aircraft, unable to sustain flight given the severity of the fire and a subsequent loss of engine power, crashed into a hotel in the village of Gonesse close to CDG, killing all 109 passengers and crew, plus four people on the ground.

Concorde was grounded for months while the accident was investigated. Although the iconic airliner briefly returned to service, the world’s 14-strong Concorde fleet was eventually retired in 2003.

In May 2004, the partial collapse of Terminal 2E at the airport hit the international news headlines. A major roof collapse had killed four people, rendering the terminal unusable for several years while it was reconstructed. The building eventually reopened in 2008.

One final CDG story with which readers may be familiar is that of Mehran Karimi Nasseri, who ‘lived’ in Terminal 1 at CDG for 18 years between 1988 and 2006.

Having fled Iran but refused entry to the UK, Nasseri remained in a diplomatic no man’s land and resided within the recesses of Terminal 1 for many years. Although offered asylum by both France and Belgium during that time, he remained at CDG until he was taken unwell and hospitalized in 2006.

Having undergone medical treatment and seemingly recovered, Nasseri was re-housed by the French authorities. However, shortly afterward, he returned to live at the airport on his own volition until November 12, 2006, when he passed away within the confines of his adopted home of Terminal 1.

Nasseri’s remarkable story inspired the 2004 film ‘The Terminal’ starring Tom Hanks, although the basic facts of the story were altered to feature an Eastern European individual living in the confines of New York-JFK Airport.

Conclusion

All three Paris airports remain operational today. While CDG has become the primary airport serving the Paris region, Orly still handles significant numbers of domestic, regional, and European flights, handling 32 million passengers in 2023.

Le Bourget is now only open to business traffic only and handles large numbers of corporate jets annually. It is also the home to the bi-annual Paris Air Show, next due in June 2025.

In contrast to other major airports both within Europe and beyond, at just 50 years old, CDG is relatively young. However, despite this, since its opening in March 1974, it has established itself as Europe’s third busiest international airport behind Istanbul-Ataturk Airport (IST) and London-Heathrow Airport (LHR).

In July 2024, the airport handled 6.6 million passengers, up 1.4% over the same month in 2023. In August 2024, almost 43,000 flights operated from the airport, serving 628 routes to 108 countries. The airport currently has a portfolio of 169 operating carriers serving its two main terminals.

There is little doubt with the foresight of those involved in its design over fifty years ago, CDG is well placed to continue growing in the future and handling increasing numbers of passengers and flights – a strategy that modern-day airport developers should take heed of as demand for air travel continues to soar in the modern age.