ETOPS (Extended Range Twin Operations) is an acronym that is used to describe the operation of a twin-engine (aircraft with two engines) over a route that includes a point that is 60 minutes away from an adequate airport.

In the early 1930s, the FAA developed requirements that restricted aircraft with two engines from flying more than 100 miles away from an adequate aerodrome. Back in the day, 100 miles was roughly 60 minutes.

This is a rule that exists to this day. There was a very important reason why this rule came about. Early piston-powered aircraft engines were not so reliable.

In other words, engine failures were not that uncommon. The “60-minute” rule thus allowed aircraft to make a timely diversion to an adequate aerodrome without compromising safety. This meant that the plane did not have direct routes. The routes had to be modified to maintain the 60-minute diversion time.

As the years went on, the reliability of the engines increased, and, with the advent of jet engines, engine failures were a rare event. And in the 1950s, ICAO (International Civil Aviation Organization), published recommendations that allowed a 90-minute diversion time for twin-engine aircraft.

As ICAO is not a regulatory body, the FAA was not obliged to follow the rules set by them. While the FAA continued the 60-minute rule, some countries did adopt the ICAO 90-minute rule for twin operations.

The advent of jet engines further increased their reliability. In 1985, the FAA laid the framework for a single-engine diversion time of 120 minutes for twin-engine aircraft. Meaning, an aircraft could have an engine failure and still be 120 minutes away from an adequate aerodrome. The CAA UK, Transport Canada, DGAC France, DOT Australia, and CAA New Zealand followed the FAA. This was the beginning of the ETOPS that we know today.

The first official ETOPS operations were carried out by a TWA Boeing 767 in 1985. However, it is important to note the fact that the Airbus A300 has been utilized by some airlines under the 90-minute ICAO rule since the late 1970s. So, the Airbus A300 was the first jetliner to use ETOPS on an unofficial basis.

The ETOPS allowed airlines to operate routes that were not possible before. The fact that an aircraft could be further from an adequate aerodrome meant that more direct routes could be flown. This reduced fuel and saved flight time.

Getting ETOPS approval

ETOPS approval is highly regulated and, contrary to popular belief, an ETOPS approval is not automatically granted to an airline or an operator simply because the aircraft they fly are ETOPS certified. ETOPS approval is given to an airline by its respective civil aviation authority after a lot of consideration. For example, an airline operating in the UK will require a permit from the UK CAA for the conduct of ETOPS.

There are two main methods by which an operator could apply for an ETOPS approval. One is the “Accelerated ETOPS approval” and the other is “In-service ETOPS approval”.

The accelerated ETOPS approval is for those airlines with no prior ETOPS experience with the aircraft/engine combination. As this type of approval is for a new ETOPS airline, the application must address the lack of experience. The operator must prove to the regulatory body that they have mitigation in place to counter their lack of experience. This includes assistance from aircraft manufacturers and having enough resources to initiate and sustain an ETOPS operation.

One of the most important parts of ETOPS approval is concerned with the maintenance side of the airline. The airline must show that they have a good maintenance program that has:

1. A proven ETOPS reliability program

2. A proven oil consumption monitoring program

3. A proven engine condition monitoring and reporting system

4. A propulsion system monitoring program

5. An ETOPS parts control program

6. A plan for resolving aircraft discrepancies

The airline must also define its ETOPS routes and the diversion time necessary to sustain those routes. They must design an ETOPS training program for their flight crew and other operations personnel.

The In-service ETOPS approval is for airlines with prior experience with an aircraft/engine combination. For example, an airline named Simple Flying Airlines operates a fleet of Airbus A320s with CFM Leap-1A engines, and they have been in operation for more than two years.

In those two years, they have gained experience working with both the A320 and its engine, the Leap-1A. If they want to apply for ETOPS, they can now go along the in-service route. In their application to the local regulator, they must show their experience working with the aircraft and the engine. The regulator will then use this information to grant ETOPS approval.

When it comes to the approved diversion time, it can only be increased with experience. For instance, a new ETOPS approval will only grant a maximum diversion time of 120 minutes. If the airline wants to increase this to say 180 minutes, they must have at least one year of ETOPS 120 experience. If an airline wants to go beyond 180 minutes, they must already hold an ETOPS 180 approval.

ETOPS operational factors

Adequate and suitable aerodromes

The ETOPS alternate aerodromes must be both adequate and suitable at the time of operation.

An adequate aerodrome must meet the following requirements:

- It should be open and available

- The operator should have overflying and landing authorization to the aerodrome

- It should have proper ground support. This includes Air traffic control (ATC), meteorological support, and proper lighting

- It must possess navigational aids such as ILS, VOR, or an NDB

- It should have rescue and firefighting capability.

A suitable airport is an aerodrome that meets the ETOPS dispatch weather requirements (ceiling and visibility) within the validity period. This validity period starts 1 hour before the earliest Estimated Time of Arrival (ETA) at the aerodrome and ends 1 hour after the latest ETA. The aerodrome also must be within the crosswind limitations in the validity period.

Photo: Arseniy Shemyakin Photo | Shutterstock

ETOPS maximum diversion time and diversion distance

We already touched upon the diversion time. It is basically the ETOPS rating. For example, an airline with an ETOPS 180 rating can only fly in an ETOPS area of operation for a maximum of 180 minutes if a reason for a diversion were to occur in an ETOPS flight. This time is then used to derive the maximum diversion distance.

The maximum diversion distance is thus, the distance covered by an aircraft within the maximum diversion time. It is calculated in still air (no winds) and international standard Atmosphere (ISA) conditions.

This maximum diversion distance is used to then define an ETOPS area of operation.

ETOPS area of operation

The ETOPS area of operation is the area in which ETOPS is conducted. It consists of an ETOPS Entry Point (EEP), an Equitime Point (ETP), a Critical Point (CP), and an ETOPS Exit Point (EXP).

EEP

The EEP is the point when the aircraft is exactly 60 minutes or 1 hour from an adequate aerodrome. Once the EEP is passed, the aircraft is officially more than 1hour from such an aerodrome. It simply marks the point where an aircraft enters the ETOPS segment of the flight.

ETP

ETP is the point in the ETOPS segment where an aircraft is located at the same flying time between two diversion aerodromes. An ETOPS flight may or may not have an ETP, or it may even have multiple ETPs depending on how long the ETOPS segment is. Shorter ETOPS flights may not have an ETP because they may be filed with only one ETOPS alternate airport. Longer ETOPS flights, however, may have, many ETPs, because the longer the ETOPS operational area means, the more possible aerodromes the aircraft can encounter.

CP

The CP is the point that marks when the aircraft is said to be critical in terms of fuel. You can think of an ETOPS flight plan with two ETOPS diversion fields. Field A and Field B. When you pass the EEP, the fuel is good to make a diversion to field A only.

As you fly past the EEP you will get further away from A and at some point, you will reach the ETP, where the time to fly between fields A and B is the same. However, once you pass the ETP, you get closer to B and so far from A that it is impossible to reach A with ETOPS diversion fuel intact. So, your only possible alternate after ETP is limited to field B. In this case, thus, the ETP point is the CP.

How is ETOPS’s area of operation determined?

We all know the simple speed formula, where Speed (S) = Distance (D) / Time (T). So, deriving an ETOPS area of operation simply involves multiplying distance and time or D = S x T. So, to define an ETOPS area of operation, we need both speed and time.

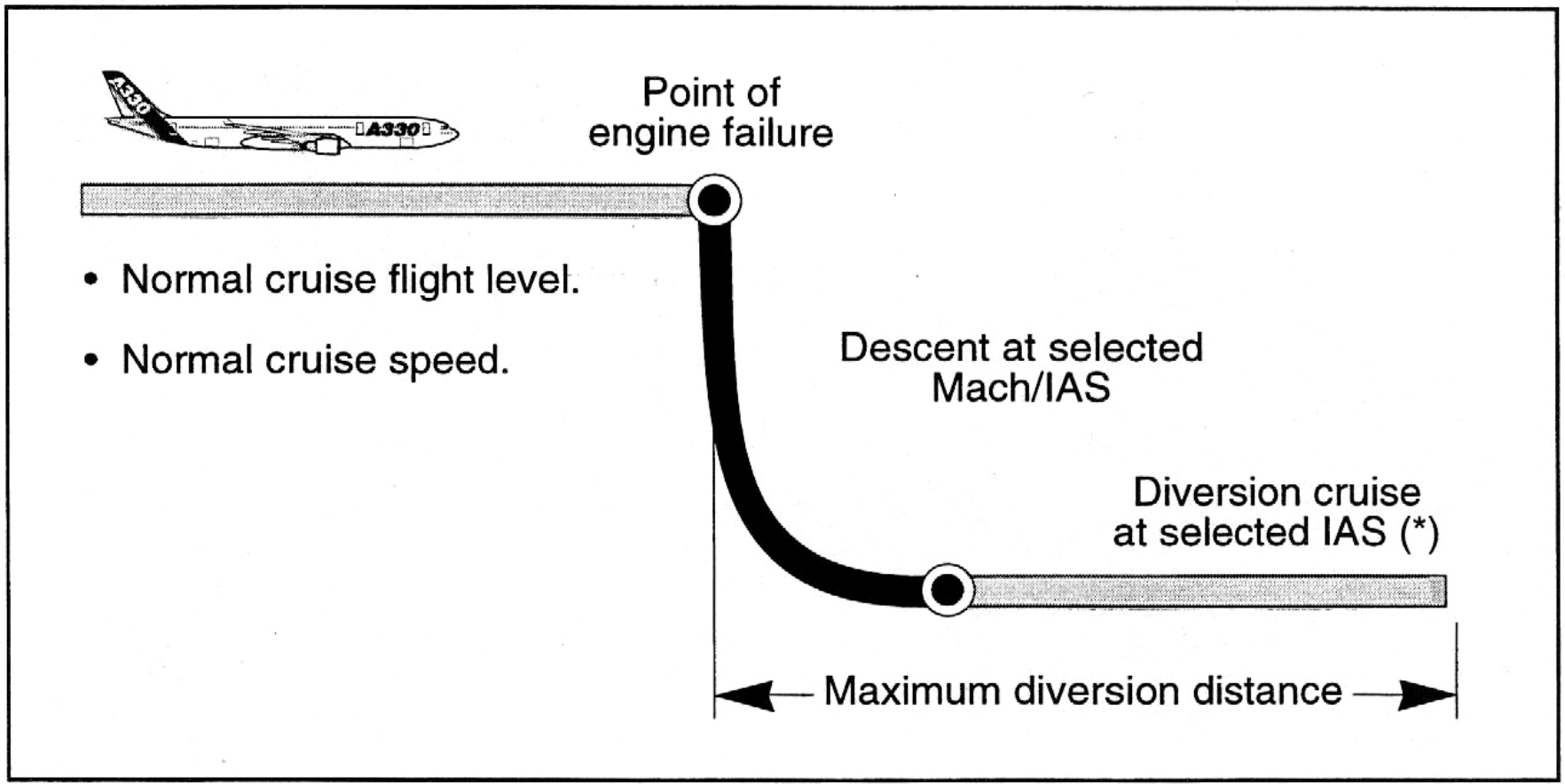

The speed for diversion is based on an aircraft with one engine inoperative. This speed is usually defined in the operator’s operational manual. The one engine speed must be such that it can cover the ETOPS operational area. For pilots, this speed is a constant Indicated Air Speed (IAS) where the actual speed is based on a True Air Speed (TAS) which changes with altitude. The TAS change with altitude for a given IAS is then used to determine the ETOPS area.

Photo: Airbus

To give an example, say an operator has a speed of 320 knots for ETOPS diversion. This is speed that must be followed by the pilot, in the subsequent descent and diversion to the ETOPS alternate. Given this speed, it is possible to derive a True Air Speed (TAS) as the aircraft descends.

So, the aircraft must descend to an altitude after an engine failure which allows it to maintain this speed. Say, the average TAS is about 400 knots and to maintain this speed the aircraft has to descend to 16,000 ft with one engine inoperative. If the ETOPS rating is 180 minutes, this gives us an ETOPS diversion distance of 1200 nautical miles. What this implies is that once the aircraft enters the ETOPS segment, it can be 1200 miles away from a possible aerodrome.

The key point to note here is that the higher the speed, the more ground the aircraft covers, and hence the larger will be the ETOPS area of operation. On the other hand, the slower the speed the lesser the ground the aircraft covers, and this in turn reduces the area of operation.

ETOPS critical fuel determination

In the part about the Critical Point (CP) it was mentioned that at CP, fuel is critical. The ETOPS critical fuel is based on three scenarios. They are:

1. Pressurization failure

2. Pressurization failure + engine failure

3. Engine failure

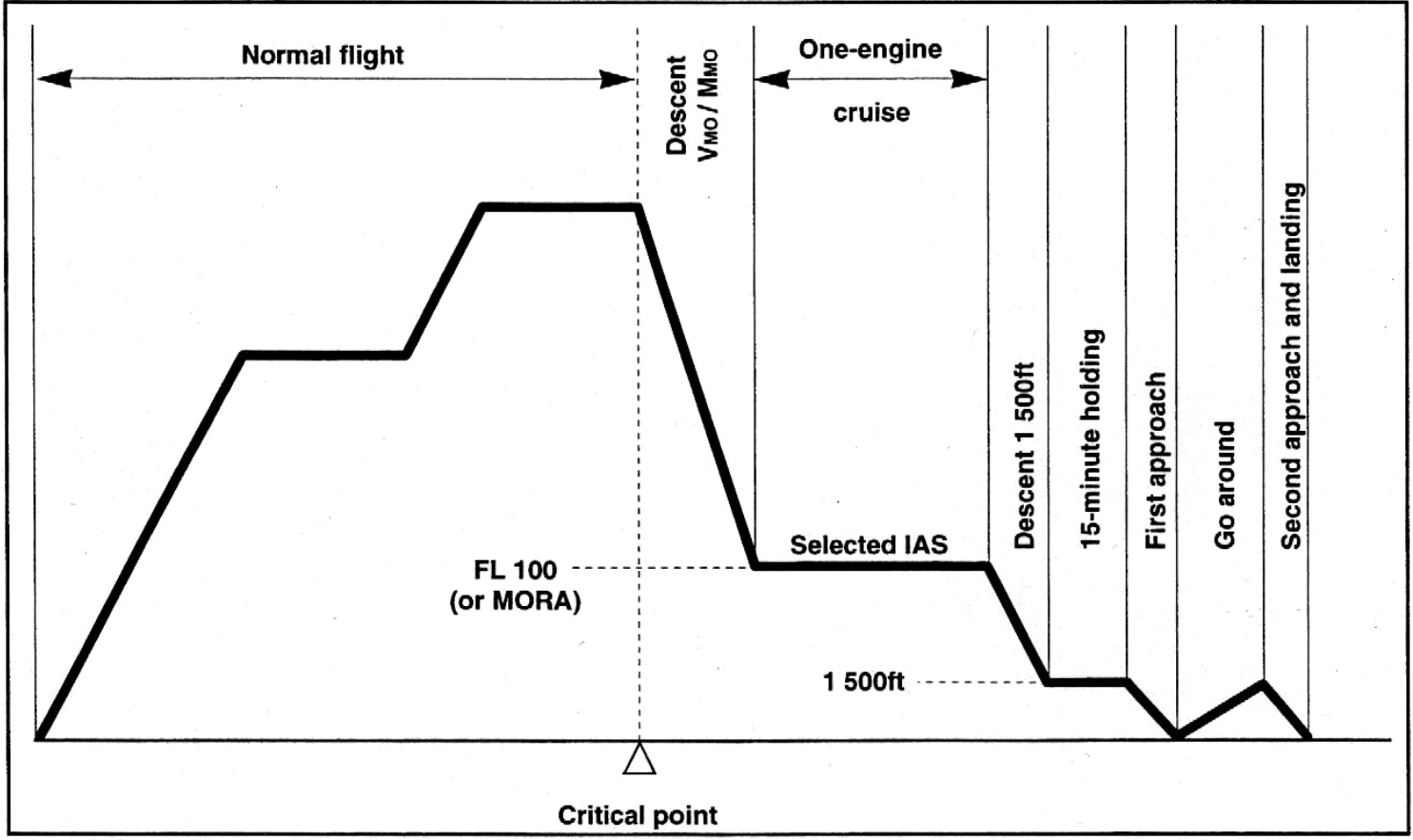

The number three (engine failure) is never limiting in terms of fuel because an engine failure does not require the aircraft to descend to a very low altitude, so fuel is conserved.

However, when a pressurization failure occurs, the aircraft needs to go down to 10,000 ft or lower so that the passengers can breathe without the continuous use of supplemental Oxygen. So, pressurization and pressurization failure + engine failure can eat away from fuel and thus contribute to the critical fuel.

Photo: Wenjie Zheng | Shutterstock

The critical fuel scenario considers the following:

- A descent at the pre-determined speed to the diversion flight level

- Cruise at diversion at a pre-determined speed

- A normal descent down to 1500 ft above the diversion field.

- 15 minutes of holding fuel at 1500 ft above the field

- An instrument approach followed by a go-around

- A second approach and landing

How you fly the ETOPS diversion is similar for both pressurization and pressurization + engine failure situations. The only difference is that, if you only have a pressurization failure, you will fly at a more conservative speed called the LRC (Long Range Cruise) speed.

This saves fuel. Because a depressurization event does not involve an engine failure, the aircraft is not limited to the ETOPS area of operation. However, if the failure is a pressurization + engine failure, the aircraft must be flown at the pre-determined speed schedule which ensures the aircraft is not flown beyond the one engine inoperative area.

Photo: Airbus

ETOPS operational and inflight procedures

An ETOPS flight begins at the dispatch stage. At this stage, the dispatchers prepare the flight plan and get the latest weather and airport information or the NOTAM (Notification to Airmen).

The dispatch weather requirement for ETOPS alternate(s) is different from the weather requirement once in the flight. During dispatch, the minima at the airport(s) are raised as follows (the table is based on EASA AMC 20-6):

|

Approach facilities |

Ceiling Visibility |

Ceiling Visibility |

|

Precision Approach |

Precision Approach Authorized DH/DA plus an increment of 200 ft |

Authorized visibility plus an increment of 800 metres |

|

Non-Precision Approach or Circling approach |

Authorized MDH/MDA plus an increment of 400 ft |

Authorized visibility plus an increment of 1500 metres |

Once the flight begins, the pilots no longer worry about the dispatch minima. They fly the normal charted minima of the aerodrome.

Photo: American Airlines

From the piloting side, the pilots prepare for an ETOPS flight by checking the flight plan and checking the weather minima and the fuel to make sure the aircraft has enough fuel to divert to the ETOPS alternate if a failure occurs in the flight.

During the pre-flight, the pilots determine the location of EEP, ETP(s), and EXP and enter it into the flight management system. The aircraft technical log is checked to ensure that all the systems that are required for an ETOPS flight are operational.

As the aircraft approaches the EEP, the pilots get the latest weather of the ETOPS diversion fields. If the weather is above the minima, the flight enters the ETOPS area.

If not, the flight might have to divert, or some other field may be taken as an alternate. Within the ETOPS segment, if the weather at the alternates were to deteriorate, the flight may be continued if the Pilot in Command (PIC) desires to do so. If the fuel were to go below the ETOPS diversion limit, the flight could also be continued given that the aircraft has already entered the ETOPS area of operation.

Photo: Atosan | Shutterstock