During the early years of aviation, the concept of powered flight was so novel that there were no manufacturers

who developed powerplants exclusively for aircraft, requiring the industry’s pioneers to get creative. Initially, engineers decided to use motor vehicle engines, which would typically be found in automobiles, to spin propellers that would be used to generate forward power for flight.

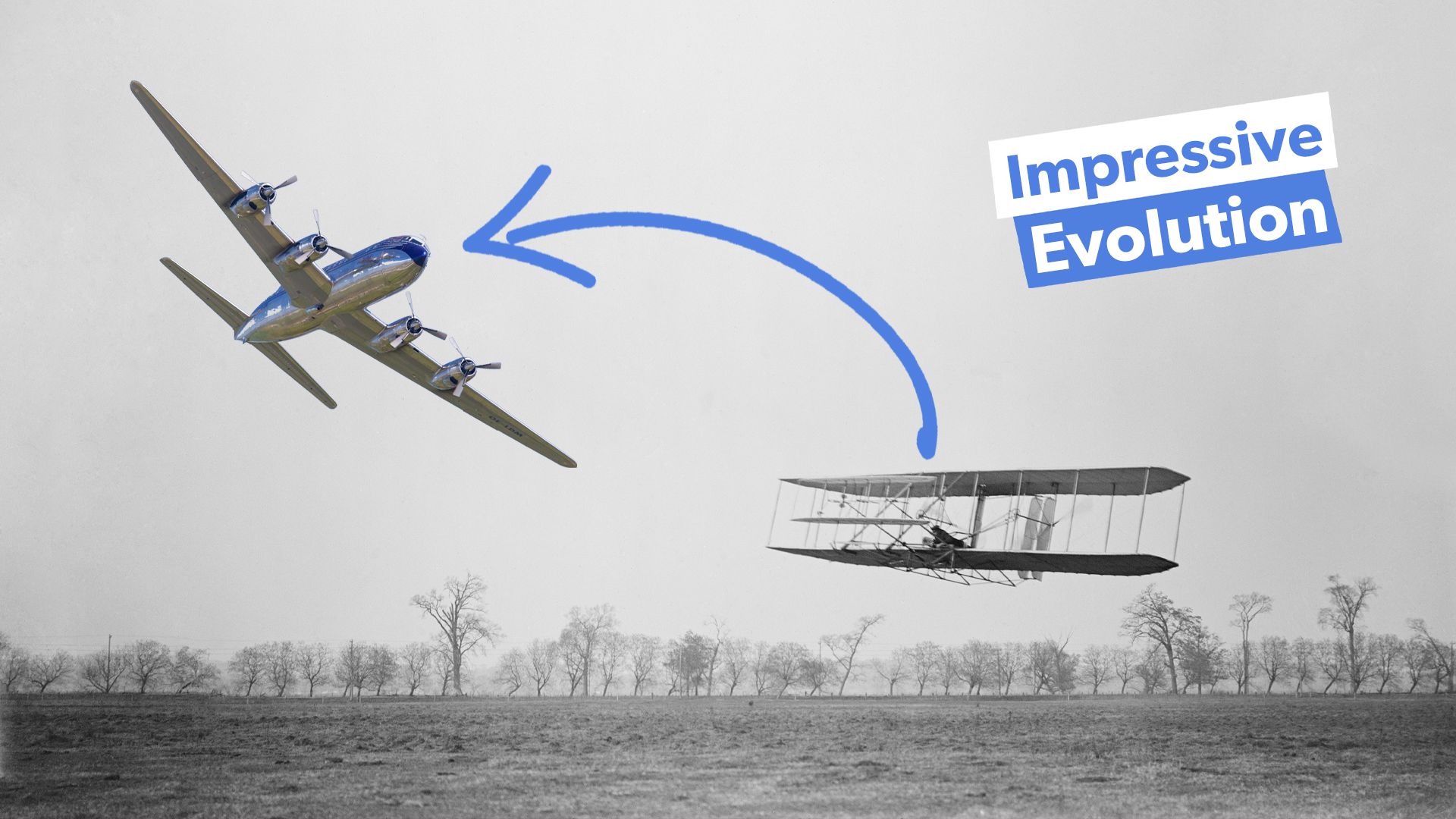

There was extensive evolution, however, between the start of the 20th century, when aviation was in its infancy, and the middle of the century, when international commercial air travel was not only widespread but slowly becoming the norm for long-haul travel. Nonetheless, the basics of the engines that all these aircraft used were relatively similar, as almost all planes during this period used reciprocating heat engines, which are commonly referred to as piston engines.

Internal combustion engines, which come in several different variants, remain the standard for automotive propulsion today, with relatively few found in aviation outside of small, single-engine general aviation aircraft. Nonetheless, the engine that you will find inside your car today looks nothing like what the Wright brothers put on their aircraft generations ago, and nothing like the engines that major airlines like the Douglas DC-6 relied on. Let’s trace the evolution of the piston engine throughout this period of transformation in global aviation.

The earliest piston engines were taken from automobiles

The original engine used by the Wright brothers, who first took to the skies in December 1903, was designed similarly to that of any automotive engine of the era. It was a four-cylinder in-line piston engine that could generate 12 horsepower, which was rather weak considering the engine itself weighed around 174 pounds, according to Eriksson and Steenhuis’ 2016 book The Global Commercial Aviation Industry.

Throughout the decade, the brothers would continue to improve their engines, with later variants offering significantly stronger power-to-weight ratios. The brothers also explored new engine configurations, such as the V-shape which is found in many cars still today. The earliest aircraft engines have both benefits and drawbacks:

- Early piston engines were heavy and had weak power-to-weight ratios

- These engines were not all that aerodynamic, leading to increased drag

- These powerplants were simple to operate, making them easy to understand, maintain and manage

An early breakthrough changed piston engine technology

In 1908, a French manufacturer, Gnome, introduced the rotary piston engine, which provided an impressive power-to-weight ratio improvement over its predecessors by arranging the cylinders in a circle around a crankshaft. This did have some drawbacks, as it required the engine to rotate constantly, which made aircraft difficult to fly and increased drag.

Over the next decade, the First World War broke out, a conflict that would have a major impact on the development of aircraft engines. Due to its capabilities, rotary piston engines became some of the most commonly found during the conflict, and thousands were produced in both Allied and enemy factories.

The Clerget 9B, one of the most-built engines of the war, powered the legendary Sopwith Camel fighter aircraft, according to the Canadian Museum of Flight. Over 10,000 Clerget 9B engines were built throughout the conflict in both Britain and France.

One challenge the rotary’s widespread use did bring along during the First World War, however, was difficulty in maneuvering aircraft. However, given the war effort, most air forces prioritized having a powerful and capable engine, accepting that many pilots would eventually be lost for the greater good.

The 1920s up to the Second World War

The radial engine, which was improved upon the rotary engine in many ways as it could be air-cooled and thus lighter, would soon become the standard engine following the war. Many commercial airlines began using early radial engines for commercial service, with powerful engines like the Pratt & Whitney R-1830 Twin Wasp soon becoming the standard for commercial aircraft like the Douglas DC-3.

Radial engines soon became far more powerful than any engines before them, with the Twin Wasp, for example, able to reach up to 1,200 horsepower. This fourteen-cylinder engine offered an impressive power-to-weight ratio of nearly 1.6, outclassing all of its competitors. Radial engines were equipped on many of the most important bomber aircraft of the Second World War. These powerplants were critical to helping maintain air power during the conflict. Some aircraft equipped with them are detailed in the table below:

|

Aircraft: |

Powerplant: |

|---|---|

|

B-17 Flying Fortress |

Wright R-1820-97 Cyclone turbosupercharged radial piston engines |

|

B-24 Liberator |

Pratt & Whitney R-1830-35 Twin Wasp 14-cylinder air-cooled radial piston engine |

|

B-25 Mitchell |

Wright R-2600-92 Twin Cyclone 14-cylinder air-cooled radial piston engine |

|

B-29 Superfortress |

Wright R-335-23 Duplex-Cyclone 18-cylinder air-cooled turbosupercharged radial piston engines |

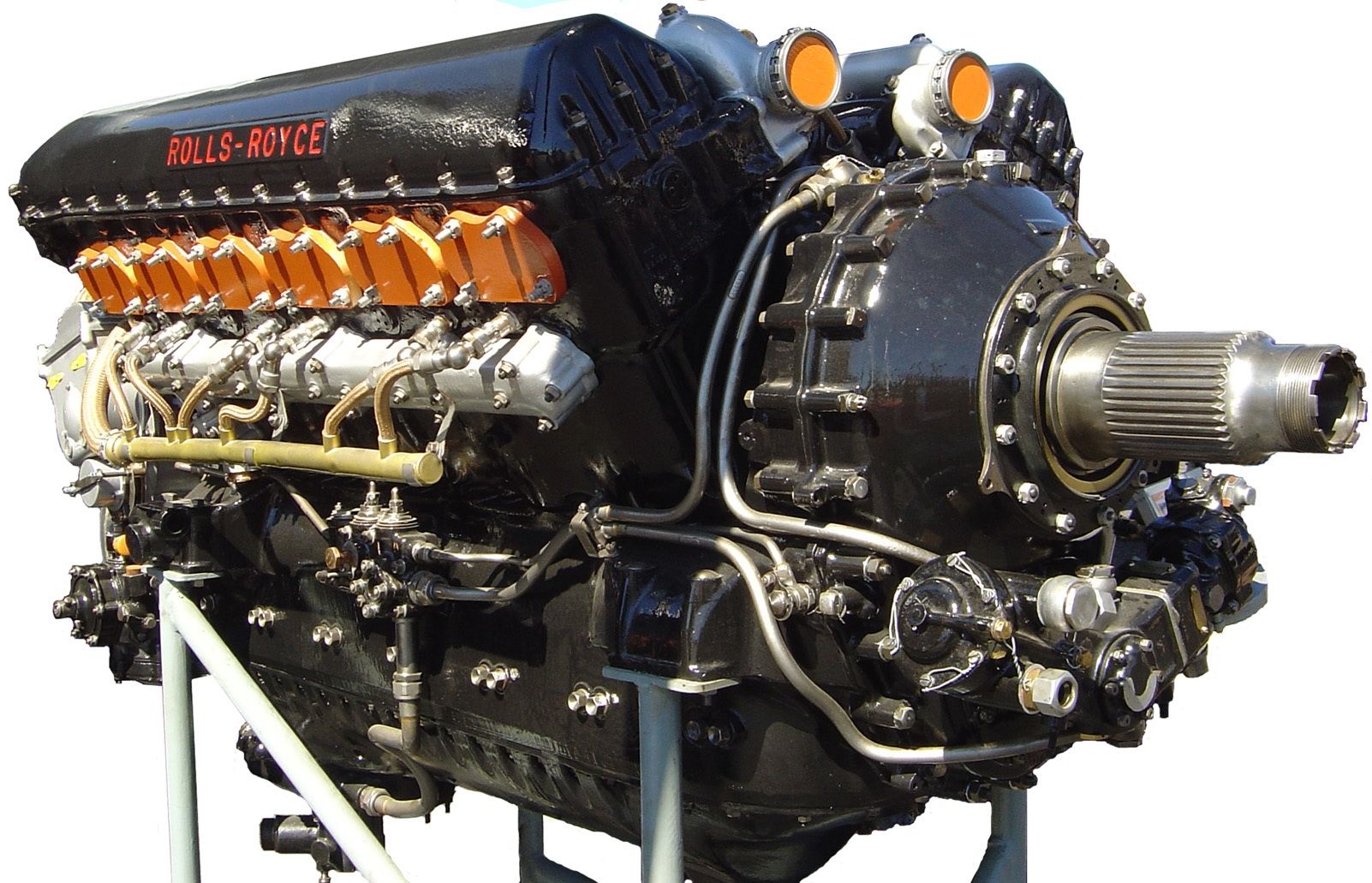

Despite the increasing popularity, some military aircraft are equipped with V-style engines. Fighters, which needed to be both light and nimble, benefited from these kinds of engines.

The final years of the piston engine’s commercial dominance

The airliners of the post-war era, such as the Lockheed Constellation and the Douglas DC-6, were equipped with some of the most powerful radial piston engines ever produced. Nonetheless, piston engines were approaching their practical limit, as they had grown heavy and bulky with additional superchargers and cooling systems.

At the end of the day, it is only so fast that you can spin a propellor before it begins to stop producing any more practical thrust. As a result, airlines and military operators would eventually turn to more powerful jet and turboprop engines, which would soon become the mainstream powerplants for large aircraft, as they remain today.