Flight attendants at American Airlines were celebrating September 12 after approving a new five-year agreement by 87 percent, with 95 percent turnout. They won a big retroactive pay package and an immediate wage increase of 20 percent.

They also became the first flight attendants to nail down boarding pay in a union contract. Flight attendants typically are not paid until the aircraft doors close. All that greeting, seating, sorting out problems, and assistance with bags is off the clock.

“The coolest thing is I had people from so many different unions across the country texting me congratulations,” said Alyssa Kovacs, a flight attendant in Chicago. Over fifty other unions had joined them at informational pickets over the years: teachers, actors, Teamsters, pilots, hotel workers. “You know, a win for one is a win for all,” she said.

It was an arduous road for the Association of Professional Flight Attendants (APFA), the 26,000-member union at American. Its previous contract expired in 2019, and then came COVID.

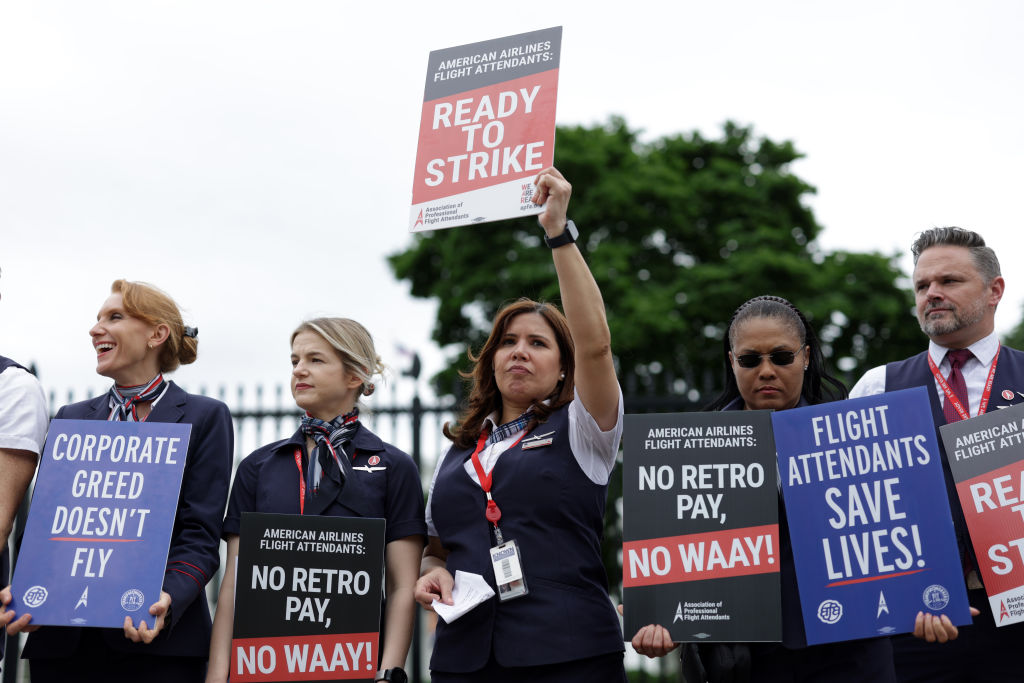

APFA’s three-year contract campaign included systemwide picketing, popular red “WAR” (We Are Ready) pins and T-shirts, seven marches on the boss, pop-up pickets at the White House and Wall Street, and last year, a 99.47 percent yes vote to strike.

“By the time we were meeting with the National Mediation Board,” said APFA president Julie Hedrick, “management, the government, everybody knew our flight attendants were ready to strike.”

In 2020, the pandemic threw the airline industry into a tailspin. Furloughs left flight attendants broke and many left the field. Those who remained faced down unhinged passengers and illness in their own ranks.

“During COVID, people spat on me,” said Evelyn Konen, a ten-year flight attendant based in Los Angeles. “They threw Coke cans at me. It was horrible. It was awful.”

But after airline business came roaring back, companies dragged out negotiations. All four of the biggest unionized US carriers — American, United, Southwest, and Alaska — have been in negotiations this year.

Flight attendants at Southwest, represented by the Transport Workers Union (TWU), finally ratified a contract in April. At Alaska, they rejected a proposed contract in August by 68 percent, with 94 percent turnout. And at United, they authorized a strike on August 28 with a 99.99 percent yes vote and 90 percent turnout. At Alaska and United, they are members of the Association of Flight Attendants (AFA).

Airline workers are covered by the Railway Labor Act, which puts up many roadblocks before workers can exercise their right to strike. Though American flight attendants voted to authorize a strike in August 2023, a year later, APFA negotiators still were going through final steps to get permission to strike. They were meeting with the National Mediation Board in Washington, DC, when they finally extracted a tentative agreement they could take to the members.

Getting there took a vigorous campaign, the strike vote, and a credible threat of striking, Hedrick said: “We had already sent out our strike booklets to the members. We had opened up a strike command center.”

APFA negotiators kept members in the loop throughout the process. “The transparency with these negotiations was a key change for this union,” said Hedrick, who was first elected in 2020. “It was an experiment — we weren’t sure how it was going to go.

“Looking back on it, it was one of the key factors in getting the members to be engaged: keeping them informed all along the way. And also when we got to the end of the process, we didn’t have to explain 40 sections of a contract to everyone.”

“It’s one thing to put out the information in the name of transparency, but it’s another to keep your membership engaged and informed and curious,” said Kovacs, who volunteered as a Contract Action Team ambassador, after the strike vote last year. She cited social media, visible presence in airports, “and then also maintaining a sense of openness, giving out my phone number, so people know, this is who I go to when I have these questions.”

APFA held detailed “town hall” meetings on contract topics, and teams of contract ambassadors like Kovacs roamed the airline’s ten base airports to discuss issues with members. The union’s website tracked the negotiation process in detail, with progress on each issue marked.

They also prioritized quickly getting the full contract to members to read (no “agreements in principle,” said Hedrick). Then members had a month to study it, and there were four more virtual town halls, a contract question hotline, and airport visits by negotiators.

Flight attendant pay is complicated. To cope, Hedrick pointed to several online calculators the union developed. “We had a retro pay calculator. We had a boarding pay calculator, because it’s a new provision, and nobody knew how much that really was. We had a trip calculator, which you could put in your schedule now and see how much more you were going to be able to make with the [new contract]. And then we had a 401(k) calculator.”

When Hedrick visited bases to discuss the tentative agreement, she asked, “How many people haven’t calculated their retro check yet?” No hands were raised.

An ongoing unionization effort among Delta flight attendants by AFA prompted that airline to introduce half-pay for boarding in June 2022, in an attempt to dampen enthusiasm for the union drive. Delta is the only big US carrier with no flight attendant union and has fought off organizing campaigns twice in the last fifteen years, through vigorous and sometimes illegal anti-union tactics, and by approximating union carrier pay rates.

However, Delta flight attendant pay is undermined by work rules workers have no control over, said Hedrick. “Delta can up the wages, but then take it away elsewhere.”

Still, Delta’s boarding pay move created a buzz among American flight attendants in 2022. “When we started the contract action team, the first thing I heard in the terminal from our flight attendants was, ‘Our union negotiators better be fighting for boarding pay,’” said Konen. “And we went out and we fought for boarding pay. And guess what? We got it!”

American flight attendants will be paid half their regular rate during boarding, as at Delta. But establishing boarding pay in the contract is the key point, said Konen. “Boarding pay is just the start of what we want to end up with, because what job do you go to where you don’t get paid from when you clock in?

“The Colosseum wasn’t built in a day, and this is a brick in the building that we want to see.”

One effect of unpaid boarding is that if you are injured — by a heavy bag, for instance — you have to fight to get workers compensation coverage because you are supposedly not yet working, Konen said.

In negotiations, American management used Delta’s pay as a benchmark. “That was the economic framework that they were stuck on, and would not budge until the very end,” said Hedrick.

Southwest flight attendants, 21,000 members of TWU Local 556, approved their contract in April with a 22.3 percent pay raise followed by 3 percent increases for the next three years, and a $364 million retro pay pool to be doled out upon ratification. Their previous contract also expired in 2019, and they rejected a first contract offer in December 2023 by 64 percent.

“When Southwest got their contract, we were like, hallelujah, somebody’s gone above Delta,” said Hedrick. But specific issues needed to be addressed at American, she said.

One additional victory is a “sit time rig” which provides for half pay if careless scheduling leaves flight attendants sitting for more than 2.5 hours between flights. This became a serious problem after American and US Airways merged in 2015, roiling schedules. “So we had like four-plus hours sitting in the terminal for no good reason just to work another flight,” Konen said

Flight attendants said they hoped that increasing the cost would cause management to rework sloppy scheduling. “Either my time is being respected by not having to wait around for as long,” said Kovacs, “or my time is being compensated.”