The Cold War was all about global competition between the United States and the Soviet Union. Of course, a primary aspect of this competition focused on weapons production and who could produce the best to gain an edge over the competitors. This eventually led to the production of anti-satellite weapons and space-based competition.

Background to the US and Soviet anti-satellite weapons competition

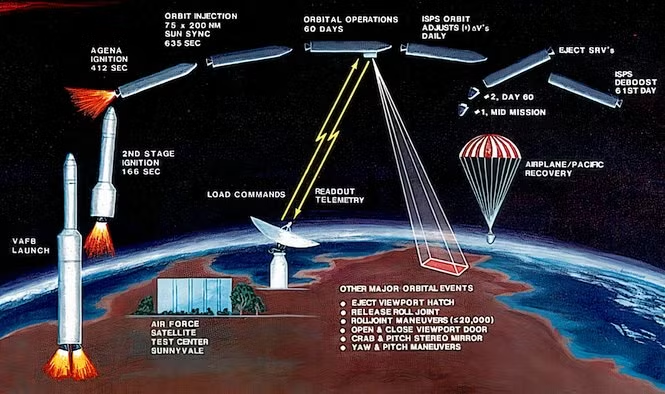

By the early 1960s, the US began emphasizing satellites for gathering intelligence on the Soviet Union (USSR). This move became one of great importance after it became clear that the USSR would be able to shoot down overflying U-2s and that the KGB had great success in intercepting American spies within the USSR.

Photo: National Museum of the USAF

An example of a US spy satellite is the 3 KH-8 Reconnaissance Satellite

|

Altitude |

65-90 nautical miles. |

|---|---|

|

Mission duration |

31 days average. |

|

Camera |

KH-8, Eastman Kodak, focal length 175 inches, aperture 43.5 inches. |

|

Film |

length up to 12,241 feet, widths 5 and 9.5 inches. |

|

Image resolution |

Objects on the ground less than 2 feet across could be seen on film exposed in orbit. |

|

Film recovery capsules |

One (two in later missions). |

|

Payload weight |

4,130 lbs. (cameras plus film). |

GAMBIT 3 satellites completed 54 missions from 1966 to 1984.

Needless to say, the Soviets absolutely loathed American spy satellites, as they had no means to destroy these omnipresent eyes in the sky. Thus, their scientists began working on anti-satellite weapons (ASAT).

As stated by Air Force Magazine:

“The USSR’s main system was the Co-Orbital ASAT, a sort of giant hand grenade for space. Launched via conventional missile, the 1.5-ton Co-Orbital interceptor lurked in orbit close to its target. Guided by onboard radar, this killer satellite would edge closer and closer to its intended target and then detonate when the target was within about half a mile. In its initial test phase, which ran from 1963 to 1972, this system intercepted seven targets during 20 attempts, and detonated five times.”

With this weapon system’s imperfect but proven ability, US military planners began to worry that the

Soviets

would eventually be able to launch nuclear weapons from space. This put greater emphasis on the US effort to develop an ASAT weapon system to confront this potential threat.

To kill a satellite

On September 13, 1985, Major Wilbert Pearson, in the cockpit of his F-15, took off from Edwards Air Force

Base in southern California (just 1.5 hours north of LA) on a unique mission: to demonstrate to Soviet Russia that the US could take out their satellites.

Photo: USAF

Major Pearson depressed the red bomb-release button. Immediately, the monstrous 3,000 pound…ASM-135 detached from…his F-15.

200 miles later, now over the Pacific Ocean and traveling Mach 1.2, Major Pearson pulled back on his control stick and began a steep 65-degree climb. This reduced his F-15’s speed to just under Mach 1, pulling 3.8 G’s in the process.

Once his twin Pratt & Whitney F100-PW-100s had propelled him to a height of 38,100 feet, Major Pearson depressed the red bomb-release button. Immediately, the monstrous 3,000-pound, experimental, two-stage missile called the ASM-135 detached from the undercarriage of his F-15.

Technical details about the amazing F-15 Eagle

|

Technical Specifications |

Numerical Data |

|---|---|

|

Crew |

2 (Pilot & Weapon systems officer) |

|

Length |

63.8 ft |

|

Width |

42.8 ft |

|

Height |

18.5 ft |

|

Empty Weight |

27,000 lb. |

|

Maximum Takeoff Weight |

56,002 lb. |

|

Maximum Speed |

1,875 mph |

|

Service Ceiling |

65,010 ft |

|

Operational Range |

2,402 miles |

|

Rate of Climb |

50,000 ft/min |

|

Onboard weapon system |

1 x 20mm M61A1 rotary cannon (six barrels) |

|

Powerplant |

2 x Pratt & Whitney F100-PW-100 afterburning turbofan engines. These units produce 25,000 lb. of thrust each. |

About the 3,000-pound satellite-killing monster

This monster of a missile was tailor-made to annihilate Soviet

satellites

, and this was the first demonstration of its capabilities on an orbiting satellite. The ASM-135, manufactured by LTV Aerospace, carried a 30 lb. Miniature Homing Vehicle (MHV) as its payload.

The incredible speed of the impact would be 36,000 feet per second.

The MHV was equipped with an infrared sensor, which enabled it to intercept a target satellite. The satellite would then be destroyed via kinetic (hit-to-kill) impact, negating the need for explosives due to the sheer speed of the impact, which was 36,000 feet per second.

The unceremonious end of Solwind P78-1

The target of the day was the 2,000-pound Solwind P78-1 satellite, situated 345 miles (1.8 million feet) above Earth. This satellite was a solar observation satellite; it was operational; however, several of its instruments had failed, relegating it to target practice.

The story continues: Major Pearson rolled to witness as the rocket ignited.

“It was just a beautiful sight to see the missile suspended there and the flame come out of the rocket motor. And then it took off like a bandit. And the rocket accelerates to about 13,000 feet per second. So you have a closure of 36,000 feet per second.”

The ASM-135 streaked skyward, blasting through the first four spheric layers surrounding the earth and locked onto the unfortunate Solwind, awaiting its unceremonious end and annihilation. According to the National Museum of the United States Air Force:

“Two solid-rocket stages propelled the missile into space, and a miniature homing vehicle (MHV) locked onto the satellite’s infrared image with a telescopic seeker. The MHV spun rapidly for stability and corrected its course with 63 small rocket motors.”

345 miles above Major Pearson, the missile raced (slightly faster than the Road-Runner) toward the obsolete satellite, moving at 17,500 mph. The result was total destruction. The MHV smashed into Solwind P78-1 with such ferocity that it immediately transformed into a cloud of metal fragments and dust.

The aftermath

Major Pearson waited until the moment he knew that the impact would have happened, then called the control room and heard cheers.

Following the satellite’s destruction, Major Pearson stated:

“It was a big day, we had hundreds and hundreds of people working very hard, for a very long time, to make this a success, and it was. It had a big impact on our adversaries because they had been very dependent on being able to put up these reconnaissance satellites, and they now knew—by demonstration—we could negate that. I think from their point of view, we made it look easy. We took off, we flew out, we pulled up, we killed a satellite. They never saw us sweat, in other words.”

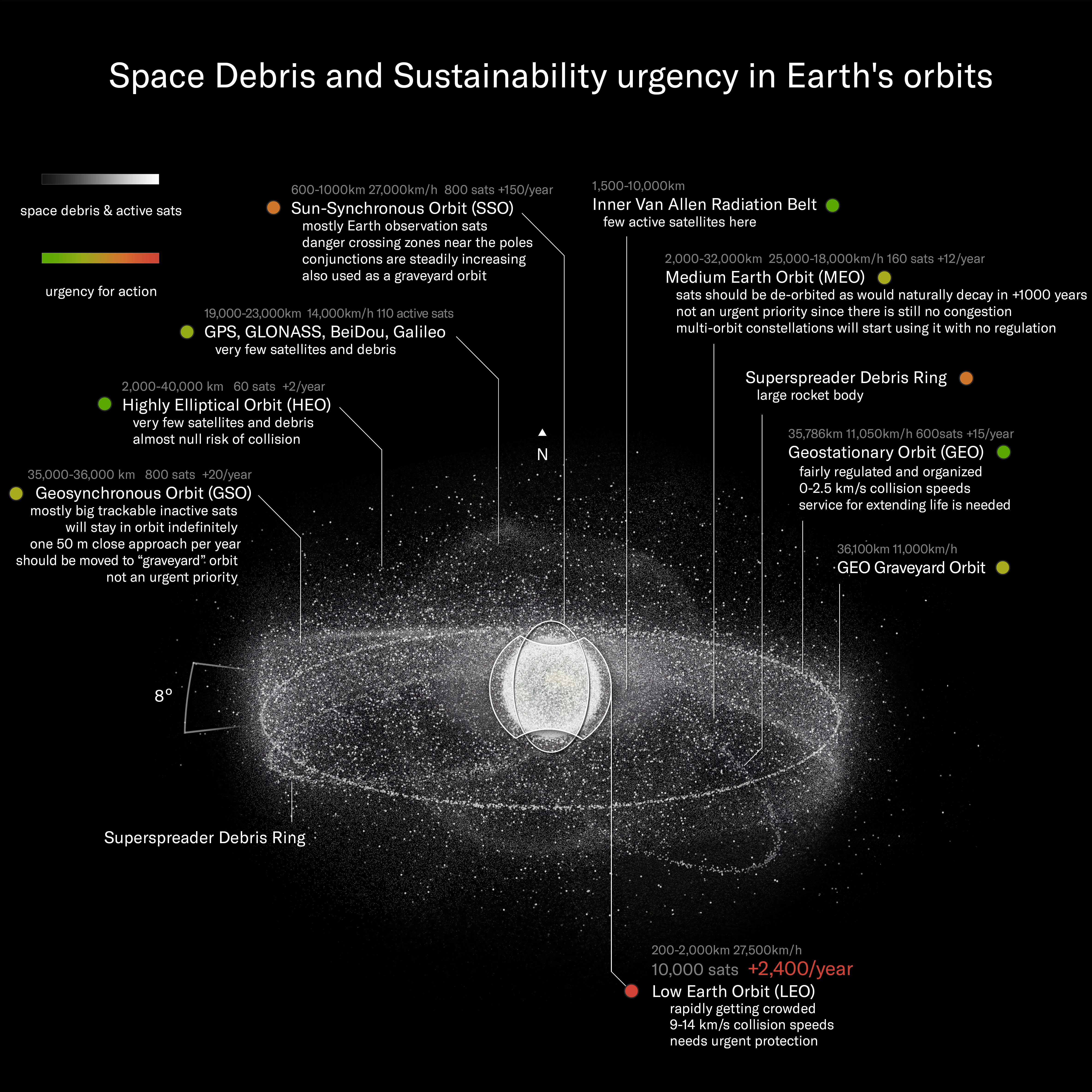

A final aspect to examine was the remnants of the destroyed Solwind P78-1. This successful test resulted in 285 pieces of debris. Subsequently, it took 19 years for all the pieces to enter the atmosphere.

The fate of the ASM-135 program

According to Air Force Magazine:

“Initially, the Air Force had planned a force of 100 Air-Launched Miniature Vehicle interceptors. They would be available to two squadrons of specially modified F-15s, split between the East and West Coast. But by 1986, the program was far over budget. Estimated completion costs had risen from $500 million to more than $5 billion.”

By 1987, the program was scaled back, and by 1988, it was canceled altogether.

ASAT weapons then and now

Like many other aspects of the 44-year Cold War, the ASM-135 program was a cat-and-mouse game. The US began to rely on satellites to spy on Soviet activities, so the Soviets created an anti-satellite weapon, and the US responded in kind.

…if hostilities begin, the satellites will be some of the first casualties.

This episode of the Cold War pointed to a future in which major powers would be dependent upon satellites for communication, intelligence, reconnaissance, and more. Because of this reliance, they are also vulnerable to attacks on these constellations of defense and commercial satellites.

The US, India and China, within the last 17 years, have all demonstrated their ability to launch attacks on satellites successfully. All of this is, of course, messaging and stark warnings that if hostilities begin, the satellites will be some of the first casualties.

Are we on the cusp of a new battle for control of space, or has it already begun? How will this end?