It was a winter day in 2009 when Chesley “Sully” Sullenberger landed a new title — hero.

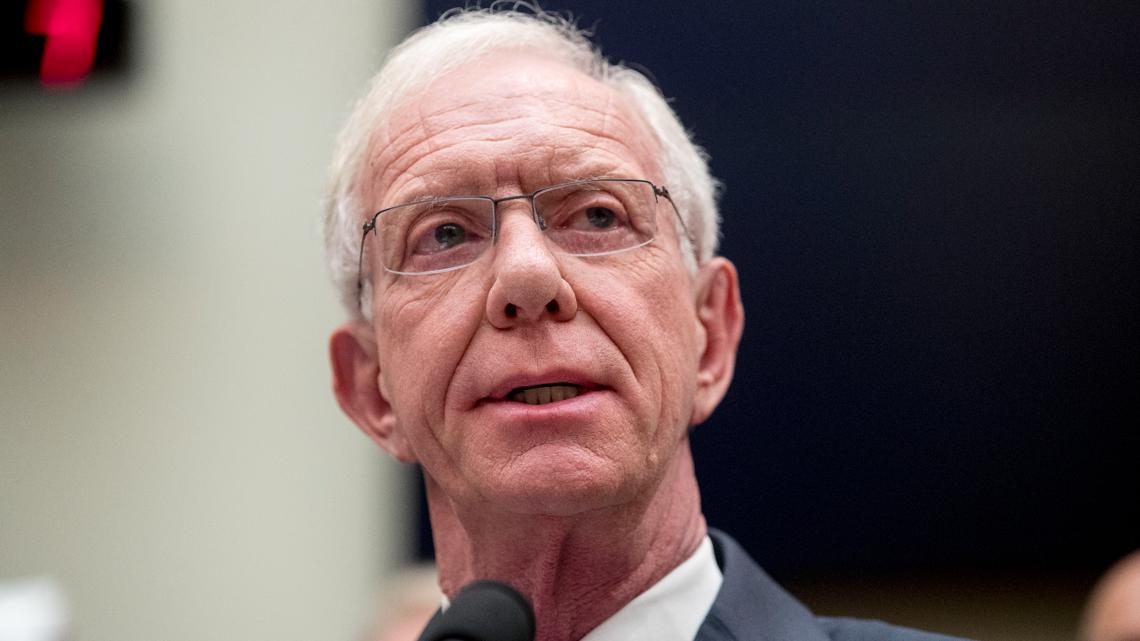

INDIANAPOLIS — More than 15 years after the emergency landing that made him famous, Chesley “Sully” Sullenberger still attracts a crowd.

“At a time when we all needed it, it gave us hope,” he said. “That’s why, I think people still remember this and it still touches and inspires people.”

It was a winter day in 2009 when the U.S. Airways pilot and Purdue University alum landed a new title — hero.

Moments after taking off from a New York City airport, Sullenberger’s aircraft struck a flock of birds. He and first officer Jeff Scott knew they would have to land the plane, but they wouldn’t make it back to the airport. Their only option: the Hudson River.

“I was confident. I never thought I was going to die that day,” Sullenberger said. “I don’t think Jeff Scott thought so, either, but I never asked him that question. We’re probably two of the few people who did not think they were going to die that day, quite frankly.”

All 155 people on board survived.

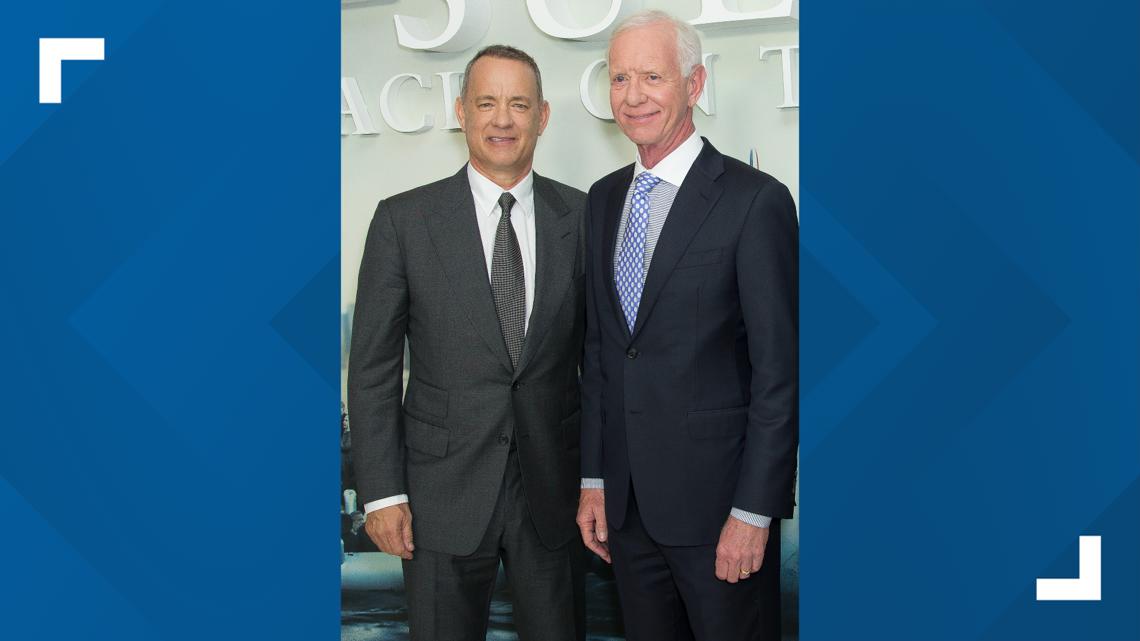

The so-called “Miracle on the Hudson” garnered Sullenberger worldwide acclaim and the story eventually became a blockbuster movie with Tom Hanks playing the role of Sully. Years after the day that changed his life, Sullenberger is still traveling the country, recounting the lessons learned.

He spoke Wednesday to a full crowd of students, faculty, alumni and Lafayette-area residents at Purdue.

Sullenberger is also a sought-after safety expert at a time when the airline industry has faced criticism for customer service and multiple mishaps on the runway and in the air.

Asked whether he’s concerned about the state of aviation safety lately, Sullenberger said “safety” is not a destination, but rather a “never-ending journey.”

“We always have things that are going to be reminders that we’re not doing everything perfectly. We’re not doing everything right,” he told 13News. “So we need to pay attention to all these reminders, all these incidents, and investigate them so that we can prevent an occurrence that’s worse.”

“It’s going to take a lot more training and attention to detail to make sure that we adhere to best practices on every hour of every flight, every day, every week, every month, every year, every decade, for a decades long career. That’s hard to do,” Sullenberger continued. “We’re almost at the point now where we’re the victims of our own success. It seems like it’s so ultra safe, and it is that we have sometimes relax and not be as vigilant as we really need to be.”

Sullenberger said the roadblocks are human nature.

“It’s hard to be that vigilant all the time,” he said. “You have to keep reminding yourself that as safe as we have made this — there’s so much at stake. As commonplace and routine as aviation has become, and as much as we take it for granted, we can’t forget what we’re really doing when we go up together in an airliner is we are pushing a tube filled with people through the upper atmosphere, seven or eight miles above the Earth, at 80% of the speed of sound in a hostile environment with outside air pressure one-quarter that at the surface and outside temperatures to minus-70, and we must return it safely to the surface every single time. In this country alone, that’s 28,000 times a day, 10.2 million times a year. We make it look easy, but it’s not. It’s hard. It’s hard to do it the right way, on every single flight, every day.”