It was April 27, 1976. ![]() American Airlines

American Airlines

flight 625, a scheduled domestic flight, had departed earlier that day from Rhode Island T. F. Green International Airport (PVD) and made a routine stop at John F. Kennedy International Airport (JFK)

in New York. The final destination was Harry S. Truman Airport, Charlotte Amalie, St Thomas in the US Virgin Islands. The Boeing 727-100 left New York just after noon with 81 passengers and seven crew onboard.

|

Date |

April 27, 1976 |

|---|---|

|

Summary |

Runway overrun caused by pilot error |

|

Aircraft type |

Boeing 727-23 |

|

Operator |

American Airlines |

|

Registration |

N1963 |

|

Flight origin |

T. F. Green Airport, Providence, Rhode Island |

|

Stopover |

John F. Kennedy International Airport, New York, New York |

|

Destination |

Harry S. Truman Airport, Saint Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands |

The crew

The captain that day was Arthur Bujnowski, a former World War two veteran and very experienced pilot who had performed 154 landings at St Thomas, including 27 in the previous 90 days and 10 landings within the last 30 days. The first officer was Edward Offchiss and the flight engineer was Donald Nestle. Working in the cabin were flight attendants, Elizabeth Pickett, aged 47, also known as Betty, Jan Chamberlain, Joan Carrera, aged 35 and Betty Bender. They were all based in New York.

What happened?

What happened?

The three-hour flight had been routine and uneventful, and the flight attendants performed their safety and service duties as they always did. They had prepared the cabin for landing at St Thomas and took their jump seats for landing. The airport was known for its short runway of 4,658 feet, and the 727 was the heaviest aircraft allowed to use it and only in one direction.

On the descent at 10,000 feet, there was a pressure spike in the cabin pressurization system, that caused temporary ear pain and deafness in some of the passengers and crew. In response, they used the manual pressurization controls to correct it. The captain asked air traffic control to cancel the IFR (Instrument Flight Rules) approach, allowing them to proceed visually instead and slowed the descent rate and in turn, the rate of increase in cabin pressure, making the cabin more comfortable.

The captain made an error on the approach, and the maximum flap setting of 40 degrees had not been applied as per American’s normal procedures for St. Thomas. The aircraft’s speed was 10 knots higher than it should have been as it crossed the runway threshold. It ‘floated’ into a turbulent gust that forced the right wing to drop. The captain tried to correct it, but the aircraft was already 2,300 feet down runway nine at touchdown and continued to float above the runway.

“I just knew something was wrong. When we came in the plane just seemed to stay in the air. I don’t know if the pilot was trying to apply power or not. It was just going on and off. As the plane got close to the runway, it wasn’t being stopped. It just did not slow down. The plane was shaking and then it buckled.”

Passenger, Flight 625 as told to The San Diego Union.

The captain forced the aircraft down to the runway, but the pilots did not use the brakes, and the captain called for a go-around three seconds later. However, the 727’s engines were slow to respond, and they could not reach the speed needed to take off. The captain then panicked and applied full brakes and forgot to apply reverse engine thrust before the aircraft impacted.

” I was sitting in an aisle seat and Mary was next to me. There was no panic at first. I think we were all too stunned. I threw my wife, head first out of the plane.”

Passenger, Flight 625 as told to The San Diego Union

Deadly impact, fire and smoke

The aircraft struck an instrument landing system antenna and overran the runway. The right-wing tip hit the ground and crashed through a chain fence. By this time, there were flames on the right side of the aircraft, fed by fuel in the ruptured wing. The fire quickly spread into the center-right side of the cabin, and there was acrid black smoke. One of the flight attendants felt the smoke was suffocating her, but could not leave her seat until the aircraft stopped. She saw the first-class cabin break apart in front of her.

” I then saw the wing come off. I saw the buckling in front of us and immediately there was a break out of fire on the right side.”

Passenger, Flight 625 as told to The San Diego Union.

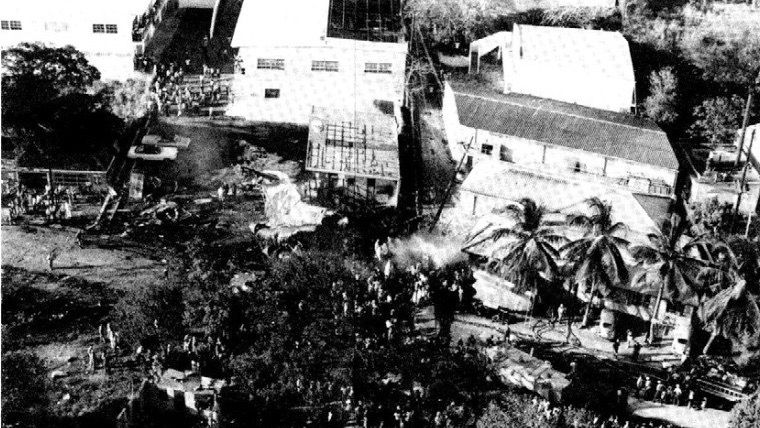

It hit an embankment before briefly becoming airborne and sliding into a Shell gas station and a rum shop on the opposite side of the airport’s perimeter road. The wreckage was spread across 375 feet. The aircraft had broken up into three pieces, and the tail section had separated. One of the surviving flight attendants was seated there and saw the fuselage break up around her. Both flight attendants had flames less than four feet away from them.

It was 15:10 local time. The aircraft was in flames and there was acrid, thick black smoke. In the cabin, the fire raged intensely in the front and center of the cabin. Survivors, including flight attendants Betty and Jan, managed to escape within seconds through the left overwing exit or through breaks in the fuselage. The flight crew escaped through the right-side cockpit window. Some passengers were overwhelmed by the fire and choking smoke before they could even take off their seatbelts. Sadly, they were caught in the inferno.

The aftermath

Fire trucks were headed for the aircraft before it came to a halt, but they were hampered by the fence, live power lines on the ground, and parked automobiles. Remarkably, the first truck got to the scene within two minutes. Bystanders, couldn’t help due to the raging fire and thick smoke. Surviving passengers walked around dazed, not really believing what had just happened. The firefighters realized that there was nothing more they could do. There would be no further survivors.

- 81 passengers, 7 crew

- 37 fatalities, including 2 flight attendants

- 39 injured, including one on the ground

- 51 survivors

There were 37 fatalities that day, including flight attendants Elizabeth and Joan. They had suffered impact trauma, smoke inhalation, and third-degree burns. Thirty-eight of the survivors were injured, and there was one injury on the ground, a man who was waiting at the airport in his car. They had fractures, burns, cuts and bruises. The aircraft was completely destroyed, as were eight automobiles, the fuel pump island, and electricity poles. The rum shop and gas station were damaged by the impact and fire.

“I saw it coming. I took off… running.”

Gas station attendant as told to the New York Times.

Final report and recommendations

The NTSB report said that the probable cause of the accident was the captain’s actions and his judgment in initiating a go-around maneuver with insufficient runway remaining after a long touchdown. This was attributed to a deviation from prescribed landing techniques and an encounter with an adverse wind condition, common at the airport.

Whilst the board did say that the accident was caused by pilot error, they also said that his actions prior to the accident were ones that he would have believed were correct due to his experience. The board suggested that the accident could have been prevented if the go-around had been performed as soon as they encountered the gust or if he’d tried to continue to stop the aircraft as soon as it touched the ground.

There is also a possibility that the pressurization problem they had just dealt with, affected the captain’s judgment of distance and speed. The three flight crew recovered from their injuries and continued to fly with American.

Airport issues and safety concerns

The NTSB board also noted that, “the airport although less than ideal, is safe” for jet operations, providing that they are “conducted within prescribed procedures.” The runway had been controversial for many years and was known to be very short for jets. There are two hills at the end of the runway and turbulent conditions were not uncommon. In 1972, the FAA had stated: “while the airport may be considered safe from a regulatory standpoint, it is a marginal airport and potential for disaster is much higher than most other airports in the region.”

After the accident, American ceased all jet flights to St. Thomas, instead operating flights to nearby La Croix. From there, passengers could take a Convair 440 turboprop operated by American Inter-Island Airlines to St Thomas. American did not return to St Thomas until the new 7,000-foot runway was built. The airport is now known as Cyril E. King Airport and still remains a popular tourist destination to this day, although no doubt the island will never forget this terrible accident.