Summary

- Sustainable aviation fuels (SAF) are not widely adopted, partially thanks to the enormous amount of energy required for production.

- Electric aviation is not yet a viable solution for reducing carbon emissions in the industry due to several limitations of current technology.

- Used Serviceable Material (USM) provides a sustainable option for replacing aircraft parts without manufacturing new components.

As aviation is a reasonably carbon-intensive industry, sustainability has, over time, risen to the forefront of airline, manufacturer, and industry-adjacent firm priorities. As we have seen, however, sustainable aviation fuels (SAF), which many have touted as the ultimate route to carbon-free aviation, are far from seeing widespread adoption, as was evidenced by Lufthansa’s CEO recently indicating that half of Germany’s electricity would be required to produce enough SAF to power the carrier’s fleet.

Electric aviation, which many have also suggested as a low-carbon solution to the industry’s high-emission nature, will likely not be widespread for decades. With current technology, electric engines are weak, ranges are limited, and development is slow.

Therefore, to decrease carbon output levels, the industry will need to continue focusing on sustainability beyond flight operations. Over time, the maintenance space has emerged as a critical area where sustainable initiatives, such as recycling, have been able to thrive.

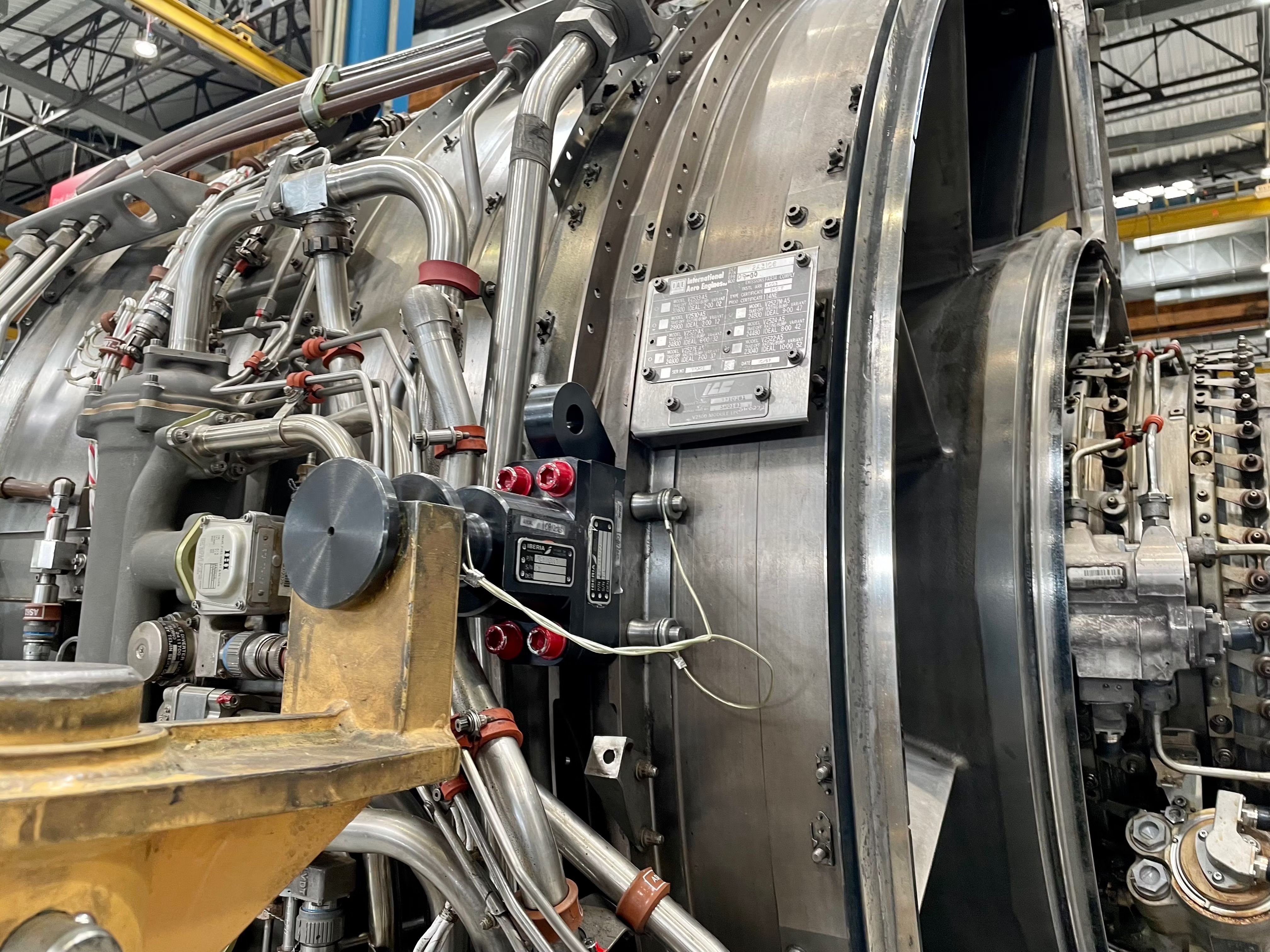

Used Serviceable Material (USM)

When an aircraft part needs replacing, either due to age or damage, an operator would traditionally aim to purchase a new component from an aerospace manufacturer. For example, if an engine cowling on an aircraft were damaged due to extreme hail, a new one could be ordered from the appropriate original equipment manufacturer (OEM).

However, operators have increasingly had a new, far more sustainable option. As opposed to the traditional process, which requires the manufacturing of a new aircraft part, the carrier can purchase a used serviceable part, allowing operators to fix their plane without the need to ask a company to manufacture an entirely new component.

Obviously, fixing a damaged or broken part with a used one can involve certain risks. For example, a component that has previously been serving with another aircraft will likely fail long before a cleanly manufactured part will. However, this will likely not be as large of a concern for older aircraft near the end of their service lives.

Photo: Finnair

Traditionally, there are two ways for an operator to take advantage of used serviceable material. The first example is relatively intuitive and involves carriers taking replacement parts from aircraft that have been retired. For instance, if a vertical stabilizer on one of Lufthansa’s A380s is damaged, the airline can simply take the part from one of their A380s still in storage (however, in this specific case, those jets may be returning to service soon).

The second method of acquiring USM can be a little more risky and involves purchasing used parts from a different operator’s retired aircraft. This can be more dangerous, as the buyer cannot be sure of the part’s condition, the former operator’s maintenance practices, and the part’s operational history.

Photo: Sumit Singh | Simple Flying

For this issue specifically, dedicated firms for used parts have emerged, including Satair, an established expert USM brokerage. In order to ensure a hassle-free buying process, the company ensures that all parts sold have received appropriate certifications. With energy prices and manufacturing shortages rising, brokerages like Satair, which provide efficient, risk-free access to high-quality parts, have made USM an attractive option for carriers.

Source: Airbus