Summary

- A midair collision between a Piper Archer and an Aeromexico DC-9 in 1986 led to critical changes in aviation safety.

- The incident highlighted flaws in the “see and avoid” system, leading to TCAS development and airspace redesign.

- In the years since the incident, there has been a significant decrease in commercial midair collisions.

On August 31, 1986, a tragic midair collision occurred over Cerritos, California, involving a Piper PA-28-181 and an Aeromexico DC-9-32. The Piper entered the Los Angeles Terminal Control Area (TCA) without authorization and collided with the descending Aeromexico flight, killing all 67 people on both aircraft and 15 people on the ground.

The subsequent investigation highlighted the limitations of the “see and avoid” concept in preventing midair collisions. As a result, significant changes were made, including the expedited development and implementation of the Traffic Collision Avoidance System (TCAS) and a redesign of the national airspace system to better separate VFR and IFR aircraft. These measures have drastically reduced the incidence of midair collisions involving commercial aircraft.

The Piper: A family vacation gone wrong

William Kramer was a 53-year-old from Redondo Beach, California. On Labor Day weekend in 1986, the private pilot had arranged a family trip for his wife and their 26-year-old daughter. The family was to fly Kramer’s Piper PA-28 Archer to Big Bear Lake, a popular vacation spot in the San Bernadino Mountains east of Los Angeles.

On the morning of August 31, Kramer prepared his aircraft for the journey. The weather was nice—a perfect day for the family to visit the cooler temperatures in the nearby mountains. All three major airports in the immediate area reported clear skies, and visibility was 14 miles, per Aviation Safety Network.

Kramer’s single-engine, four-seater Archer was kept at Zamperini Field (TOA) in Torrance, California. Although this was just 91 miles from the family’s destination at Big Bear City Airport (RBF), getting there would not be as easy as simply flying in a straight line. To reach his destination, Kramer would have to cross the Los Angeles Terminal Control Area.

Terminal Control Areas (TCAs) or Terminal Maneuvering Areas (TMAs) were established at major US commercial airports in the early 1970s. Per Skybrary, TCAs are designated areas of controlled airspace surrounding high-traffic airports and are designed to safely and efficiently manage the entry and exit of air traffic in the area.

Per the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), an aircraft desiring entry into a TCA must receive explicit permission from Air Traffic Control (ATC) and have a Mode C capable transponder. Because Kramer’s Piper PA-28 was a typical VFR aircraft equipped with only a Mode A capable transponder, he was barred from entering the TCA.

Navigating the Los Angeles airspace around the TCA would not be easy, as the boundaries were complicated. Additionally, Torrance Municipal Airport (TOA) was less than 10 NM south of Los Angeles International Airport (LAX), meaning that the smaller airport lay underneath the 5,000-foot TCA floor. VFR traffic, such as Kramer’s Piper, was forbidden from ascending above this altitude. Kramer seemed aware of these restrictions, as he filed a flight plan indicating an en route altitude of 9,500 feet, keeping him above the TCA lobe.

At approximately 11:41 Pacific daylight time (PDT) that Sunday, Kramer and his family departed TOA and lifted into the skies, climbing eastbound over the Los Angeles suburbs. It was the last time they would ever feel the ground beneath their feet.

Aeromexico Flight 498: Hermosillo’s final leg

Meanwhile, Aeromexico Flight 498 was performing a regularly scheduled flight from Mexico City to Los Angeles, with stops at Guadalajara, Loreto, and Tijuana. The aircraft was a 1969 McDonnell Douglas DC-9 named Hermosillo, a name derived from the Spanish word for “beautiful,” hermoso/a.

On August 31, Hermosillo carried two pilots, four flight attendants, and 58 passengers. At 11:44, the aircraft began descending from 10,000 feet for an instrument approach and landing at LAX.

At 11:47, the flight was connected with the Los Angeles TRACON east approach radar controller, a 35-year-old named Walter White. White gave the Aeromexico flight instructions, guiding them into the southern segment of the TCA that existed specifically to protect aircraft approaching LAX from the southeast.

As Hermosillo and its passengers crept closer to their destination, White juggled the incoming calls from other aircraft seeking passage through the crowded airspace. When a call from a VFR flight, a Grumman AA-5B Tiger, requested guidance on a route that would send it straight through the middle of the TCA, White quickly checked the traffic to determine if he needed to relay any airspeed changes to Aeromexico Flight 498.

Simultaneously, White’s supervisor informed him that the DC-9 could land at Runway 24R instead of the planned 25L. White passed the information on to the Aeromexico crew, telling them to stand by and maintain their current speed. He mentioned the presence of a small VFR aircraft at the DC-9’s 10 o’clock position, which was not a threat, and then returned to set up flight following for the Grumman. The time was 11:52.

Related

How Air Traffic Control Works To Keep Aircraft Flying Safely

ATC is a complex process with thousands of moving pieces.

As Walter White organized his section of the busy airspace, Kramer’s Piper was steadily climbing eastbound to its cruise altitude. At 11:49 and 47 seconds, the PA-28 crossed the TCA boundary, deviating from the VFR flight plan Kramer had filed (but not activated) before takeoff.

Although the Kramers’ aircraft would have been visible on White’s display, the many tasks at the moment meant that the controller never saw the plane. No mention of the Piper was ever relayed to the Aeromexico crew. Despite the clear blue skies that August day, neither Kramer nor the DC-9’s pilots ever saw each other.

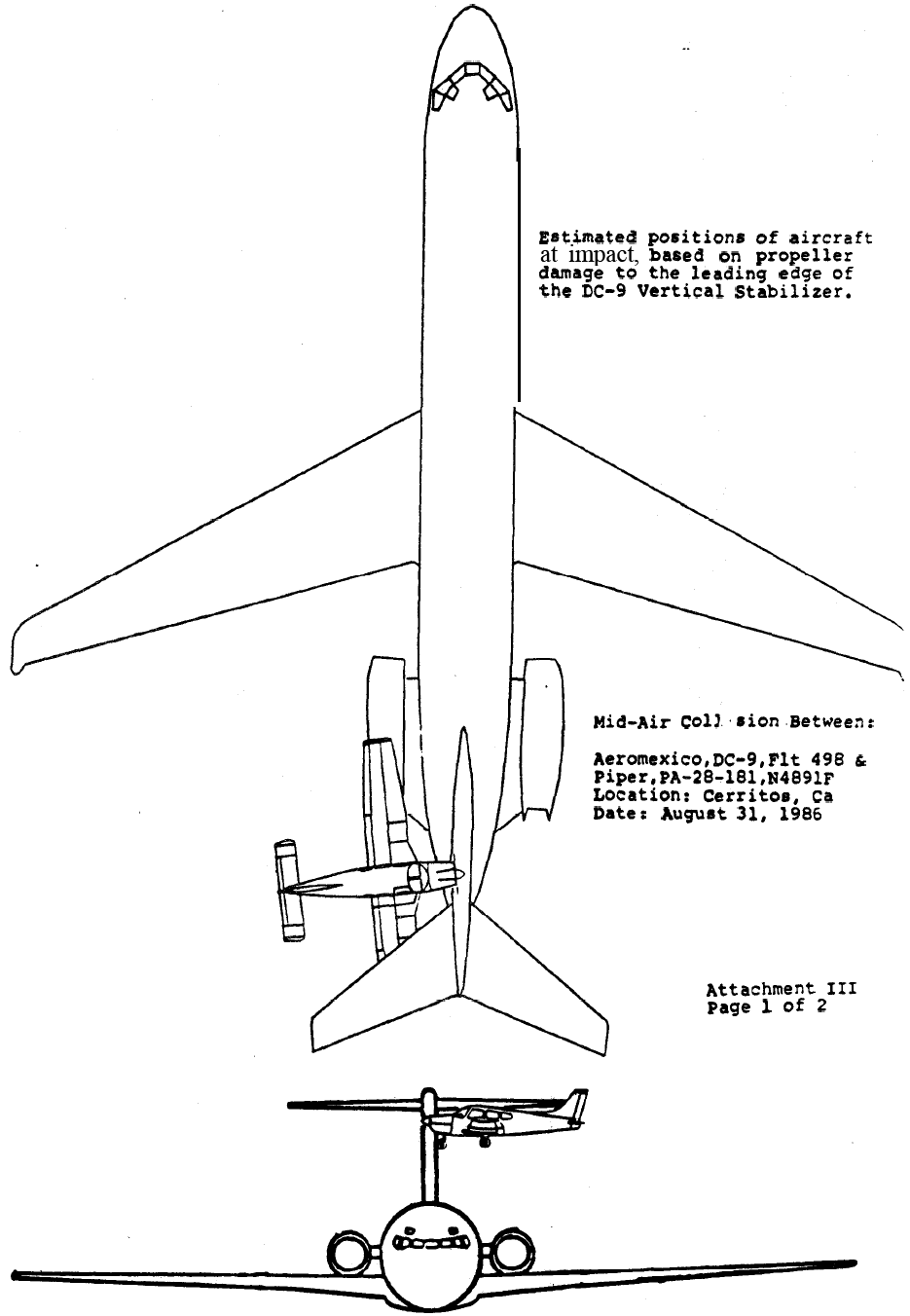

At approximately 11:52 PDT, Kramer’s PA-28 smashed headfirst into Hermosillo’s tail at 6,650 feet above the suburbs of Cerritos, California. The Piper’s engine hit the upper portion of the DC-9’s vertical stabilizer at a 90-degree angle, and the leading edge sliced through the smaller aircraft at window level. All three passengers were decapitated instantly.

The impact ripped off Hermosillo’s vertical and horizontal stabilizers, and the aircraft immediately pitched into a steep vertical nosedive. The plane rolled inverted, smoke trailing behind it like a dark ribbon across the cerulean sky. The cockpit recorder onboard gives a horrifying look into the last moments aboard the Aeromexico flight, with the captain crying out,

“Oh god, this can’t be!”

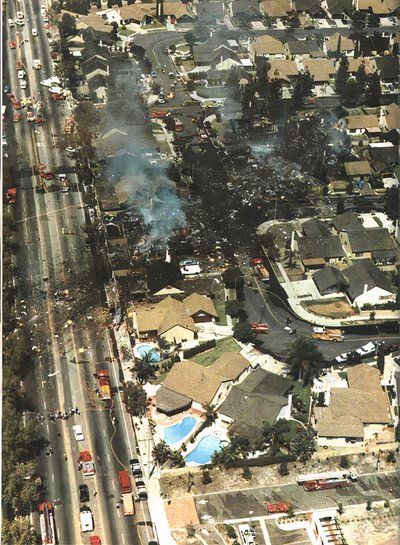

The DC-9 fell for 23 seconds, its pilots futilely trying to regain control, until it finally crashed nose-first into the homes at the corner of Holmes Avenue and Ashworth Place in the Cerritos suburbs. The Los Angeles Times described the incident and the explosion that followed as:

‘A sledgehammer from the sky.’

The wave of fiery debris flattened houses on the previously quiet street, slammed through a boundary wall, and finally came to a stop on a four-lane street. The Piper, heavily damaged and without a pilot, crashed nearby on the playground of Cerritos Elementary School.

Per accident reports and as described on This Day in Aviation, the Aeromexico wreckage and subsequent fires destroyed five houses and damaged seven others. Fifteen people on the ground were killed, along with the 67 people aboard the two aircraft. Eight people in the Cerritos neighborhood were injured, and the streets were littered with wreckage and body parts.

Although this occurred on a Sunday, which meant no children were on the playground to witness the Piper’s crash, it also meant most of the residents of the Cerritos neighborhood were home rather than safely away at work or school. According to a detailed retelling of the incident on Medium, the family at one of the five destroyed houses had been hosting a holiday pool party that day. This concentration of people at the wrong place at the wrong time added significantly to the death toll.

Related

History: 5 Major Air Disasters That Were Easily Preventable

Due to modern safety advancements made available on aircraft, Human error is the leading cause of accidents and incidents.

Who’s to blame?

The horror of the crash was felt by more than just the families of the 82 victims. Bystanders who witnessed the crash captured images of Hermosillo’s final moments plummeting toward the earth, leaving them with images they would never be able to forget. Many people who were uninjured by the incident still lost their homes to fires, and the entire neighborhood was confronted with a scene that looked like something from a horror film.

First responders to the scene were forced to comb through flaming debris to find the remains of passengers who, upon waking that morning, believed they’d be spending the day in sunny Los Angeles. Walter White, the air traffic controller, left his post that afternoon in utter anguish.

Families across America and Mexico joined in their grief and wondered how this could have happened. Many sought answers, particularly considering a similar incident that occurred just eight years earlier involving a Pacific Southwest Airlines Boeing 727 colliding with a Cessna over the San Diego suburbs. Whether asked in English or Spanish, the question for everyone was the same: How could this have happened again?

Related

The Story Of The Mid-Air Collision Involving Pacific Southwest Airlines Flight 182

How a bright sunny Californian autumn morning turned into horror for all those involved in this disaster.

Because Kramer had clearly violated the rules regarding entry into a TCA, some people initially pointed the blame at him. Kramer was not a professional pilot, having only been licensed by the FAA for six years and having 231 total flight hours. Additionally, Kramer had moved from Spokane, Washington, to the Los Angeles area less than a year before the incident, meaning he had just 5.5 flight hours in the busy airspace surrounding his new home.

Still, others blamed Walter White, the air traffic controller, for not noticing the Piper on his display screen and failing to warn the Aeromexico crew of its presence. People wondered whether White would have been able to prevent the accident from ever occurring if he hadn’t been so task-saturated at the time.

When questioned after the accident, White testified that he never saw the PA-28’s radar target on his display. According to his statement,

“It is my belief that he was not on my radar scope.”

However, the radar playback from August 31 showed the Piper moving east, marked with the standard triangle and generic “1200” transponder code. The NTSB also ruled out any malfunctions that would have prevented this from appearing on White’s display at the time of the incident.

Even if Kramer’s aircraft had been clearly visible to White, it did not mean the controller would have seen it. The very nature of his job meant that he was focused on preventing conflicts between IFR aircraft and that the separation between IFR and VFR aircraft was of lesser importance.

The system made it difficult for controllers to determine the risk of conflicts involving VFR aircraft unless the pilots reported their altitude to ATC, which was uncommon. Therefore, controllers like White could not give specific instructions to either party and instead could only provide IFR flights with general traffic alerts containing the distance and clock position of nearby VFR aircraft.

Despite the inherent need to point the finger at someone, the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB)-led investigation into the incident did not place blame on any of the individuals involved. Instead, their investigation concluded that the primary cause was the limitations of the air traffic control system in providing collision protection. According to their report, the factors contributing to the incident were:

- The inadvertent and unauthorized entry of the Piper PA-28 into the Los Angeles TCA

- The limitations of the “see and avoid” concept are to ensure traffic separation under the conditions.

The aftermath: Sweeping changes

In the wake of two similar tragic air incidents in less than a decade, the FAA and NTSB recognized the need for changes to air traffic control systems.

Even if White had seen the PA-28 and warned the Aeromexico flight of its proximity, the planes could still have collided. The practice reigning supreme at the time was “see and avoid.” Per the FAA’s flight rules prescribed in Title 14 of the Code of Federal Regulations Part 91:

“…when weather conditions permit, regardless of whether the operation is conducted under instrument flight rules (IFR) or visual flight rules (VFR), each person operating an aircraft shall maintain vigilance so as to see and avoid other aircraft.”

While the “see and avoid” concept is clearly effective, officials have known since the 1950s that the practice alone is not enough to reduce the rate of midair collisions appropriately. A 1956 report by the Civil Aeronautics Administration stated:

“Only general use of proximity warning devices will substantially reduce the steadily increasing threat of midair collisions.”

A 1991 study on the efficacy of see and avoid found that pilots in a pattern only spotted 56% of encroaching aircraft without being warned in advance. This percentage increased to 86% when pilots received an automated traffic alert.

Even by the time of this incident in 1986, some of the issues with the see and avoid policy were very well documented. These shortfalls included:

- Small VFR aircraft are hard to spot until they are dangerously close.

- To the observer aircraft, planes on route to collide with another aircraft will not appear to move against the background, making it difficult to determine the risk.

- The accuracy of spotting aircraft from the sky is limited by the human visual system, and parts of the cockpit structure can block views.

The FAA had already been working on a system that could warn aircraft of approaching traffic, regardless of ATC’s input. After this new tragedy, plans for the system were expedited.

By 1987, the Traffic Collision Avoidance System (TCAS) had been developed and was tested at several US airlines. TCAS works independently of ATC and uses nearby aircraft’s transponder signals to provide pilots with guidance to avoid potential conflicts in the sky.

The mandated installation of TCAS in aircraft with more than 30 seats and a maximum takeoff weight greater than 33,000 pounds resulted in immediate changes. Since the system’s implementation, there has not been another fatal midair collision involving a US passenger airliner.

Related

What Is TCAS And How Does It Work?

A look at how technology helps prevent aircraft from coming too close to each other.

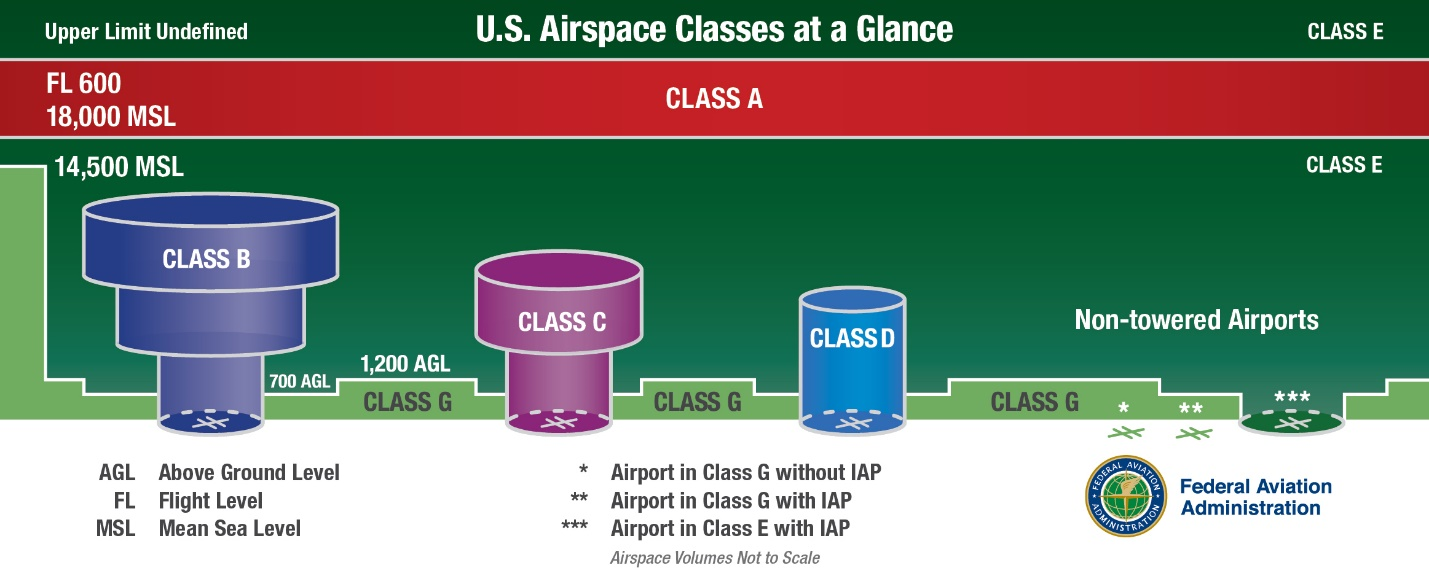

Additionally, the FAA redesigned the national airspace system to keep VFR and IFR aircraft separate. After an initial reworking of TCA requirements, the FAA eventually came to a better solution. They divided US airspace into several standardized classes, greatly simplifying the system and making it much easier for IFR and VFR aircraft to avoid one another in the skies.

Since further improvements to air traffic warning systems, including Automatic Dependent Surveillance-Broadcast (ADS-B) technology, midair collisions involving commercial aircraft have fallen dramatically. By 2014, the rate of these types of incidents had decreased by more than 80% since the Aeromexico Flight 498 collision.

While the tragedy in Cerritos is objectively horrific, it has provided important necessary changes in aviation safety. The impact and significance of the disaster will be felt for years to come, both in the skies above and on the ground below.