Summary

- Swissair flight 111 experienced a fire in the cockpit due to an arcing wire from the inflight entertainment system making contact with insulating material, leading to loss of control and crash into the Atlantic Ocean.

- The crew followed checklists but shutting off fans allowed the fire to spread, and the captain was unable to fight the fire before losing control.

- The Transportation Safety Board of Canada identified inadequate material flammability standards as the main cause of the crash, with contributing factors including rapid power failures and loss of control.

It was September 2, 1998. Swissair flight 111, was preparing to take off from John F. Kennedy International Airport bound for Cointrin Airport in Geneva, Switzerland. The McDonnell Douglas MD-11 had 215 passengers onboard and 14 crew. The cabin crew performed the safety demonstration during the taxi and secured the cabin ready for take-off, just as they always did.

The crew

The captain was Urs Zimmerman and the first officer was Stefan Loew. Maître de cabine Rene Oberhansli, was leading the cabin crew team. His cabin crew that day were: Irene Betrisey, Raphael Birkle, Patricia Eberhart, Jeannine Pompili, Seraina Pazeller, Colette Furter, Anne E. Castioni, Regula Reutemann, Peter Schwab, Brigit Wiprachtiger and Florence Zuber. Most of the crew were Swiss and two were American.

The flight

Swissair 111 took off at 20:18. Strangely, there was no communication with air traffic control (ATC) for 13 minutes after take-off. It is thought that the radios were not tuned in to the correct frequency. At 22:10, the flight crew detected an unusual odor in the cockpit. They thought that it might be coming from the air conditioning system.

Four minutes later, they detected it again and saw a few whiffs of smoke. They called in one of the cabin crew who was working in first class, to check if she could smell the odor. She confirmed the odor and stated that it was not in the cabin. At this time, the cabin crew would have been in the middle of the meal service on the MD-11 and would have been busy in the cabin.

Pan-Pan and diversion

The pilots made a ‘Pan-Pan’ radio call to Moncton ATC but did not declare an emergency. They requested a diversion to Boston before accepting ATC’s suggestion to divert to Halifax, which was nearer. They were handed over to Halifax ATC. The captain called the maître de cabine, Rene and informed him that they would be diverting to Halifax.

Rene made an announcement to the passengers that they would be diverting to Halifax and would be landing in 20 minutes. The cabin crew would clear the cabin and start to prepare for landing. One crew member was called into the cockpit to get the captain’s flight bag so that he could get the charts for Halifax. There was no sign of smoke in the cabin.

No declaration of emergency?

The flight crew were now on oxygen. ATC informed them that they were just 55 kilometers away from the airport. They requested more distance to allow them to descend from 21,000 feet and dump fuel to reduce the aircraft’s weight for landing. They followed the checklist for ‘smoke of unknown origin’. There was no sign of emergency in the cockpit.

Little did they know, that a wire from the newly fitted inflight entertainment system (IFE) had arced and in turn, this had ignited insulation material just above the cockpit. The odor was a fire in the ceiling that was coming through the air conditioning vent.

Related

Emirates Flight 521: A Cabin Crew Perspective

An evacuation in reality.

What happened next?

Following the checklist, the flight crew shut off the power to the cabin, which stopped the fans in the cabin ceiling from recirculating. In the cabin, they were plunged into darkness. Ironically, because of a design flaw, the IFE remained switched on. The cabin crew returned to their stations to collect flashlights. Rene made an announcement saying that the lights were off, but they should remain calm.

Shutting off the fans, unfortunately, led to the fire spreading in the cockpit. The fans had been drawing the fire away from the cockpit and towards the galley. The power was also shut off to the autopilot and they now had to fly the aircraft manually. In the cabin, the crew were securing the cabin for landing by flashlight. There was still no sense of this being an emergency.

Emergency declared

Ten minutes later, they would declare an emergency and that would be the last transmission. The fire tore through system after system, but they continued to fly for six minutes. There were flames in the cockpit, the radios were dead and the black boxes stopped recording. The first officer continued to fly the aircraft despite having no instruments and no visibility outside.

The captain left his seat to fight the fire and was overcome by the smoke and flames. The cockpit ceiling was melting and drops of red-hot aluminum fell on the observer’s jumpseat. The first officer would have been severely injured or dead by this point. The passengers would not have known what was going on in the cockpit.

The crew would have known there was something amiss and may have started preparing for a planned emergency landing but with so little time available and the fact they had less than 20 minutes to landing would suggest they planned for a diversion only. They had no idea that there was a full-blown fire in the cockpit.

The aftermath

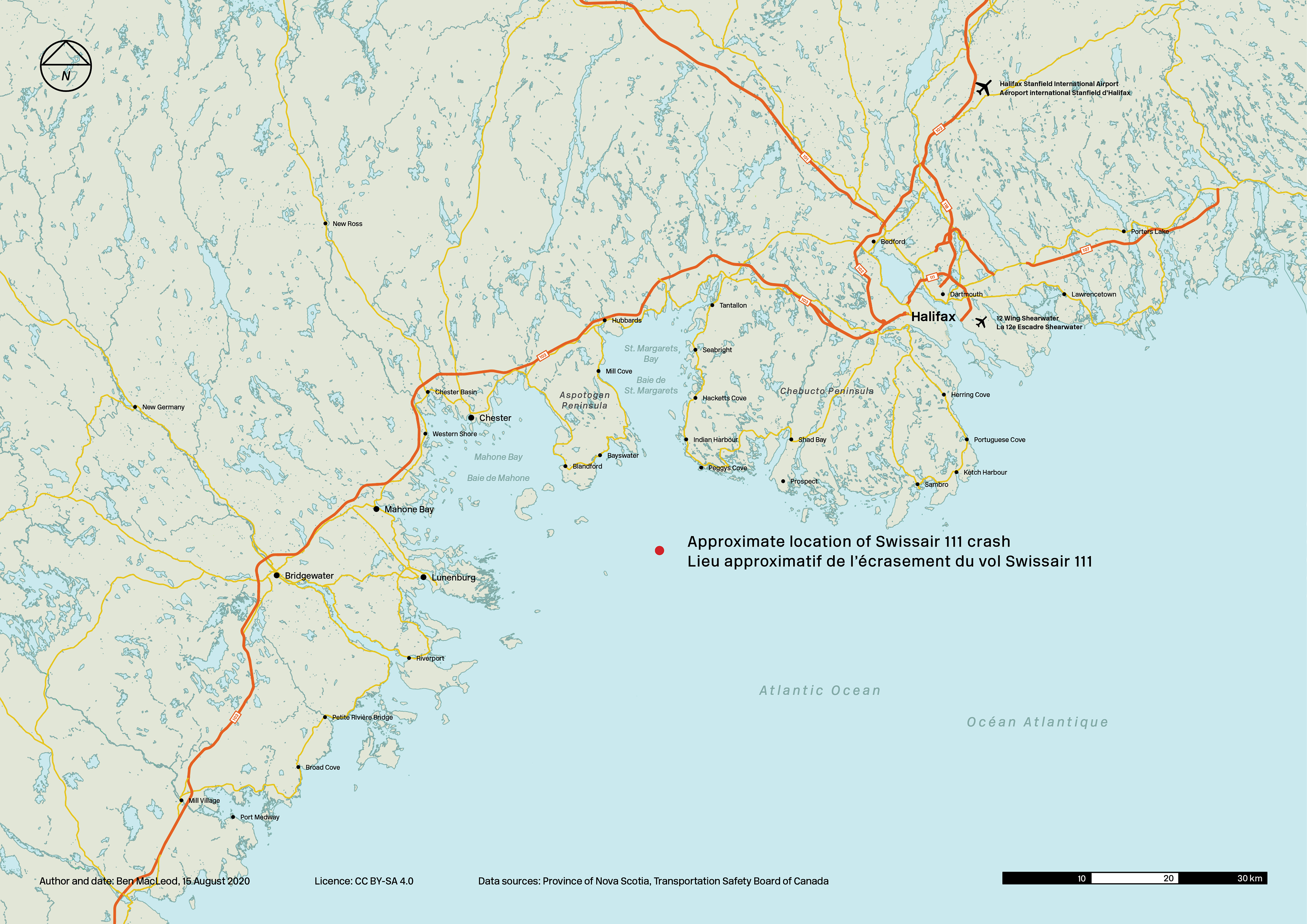

At 22:31, the MD-11 crashed at 345 mph into the Atlantic Ocean at Margaret’s Bay, Nova Scotia, killing all 229 souls on board. Death would have been instant due to the sheer impact force and deceleration. The aircraft and all inside just disintegrated and most fell to the bottom of the ocean. Some pieces were spotted floating on the ocean surface and some washed up on local shores.

Search and rescue teams codenamed ‘Operation Persistence’ were launched immediately. Ambulances and helicopters were also sent out. The search continued until the next afternoon, but it was clear that there were no survivors. Only one body was visually identifiable. 147 were identified by fingerprint, dental records and X-ray comparisons. The remaining 81 were identified using DNA tests.

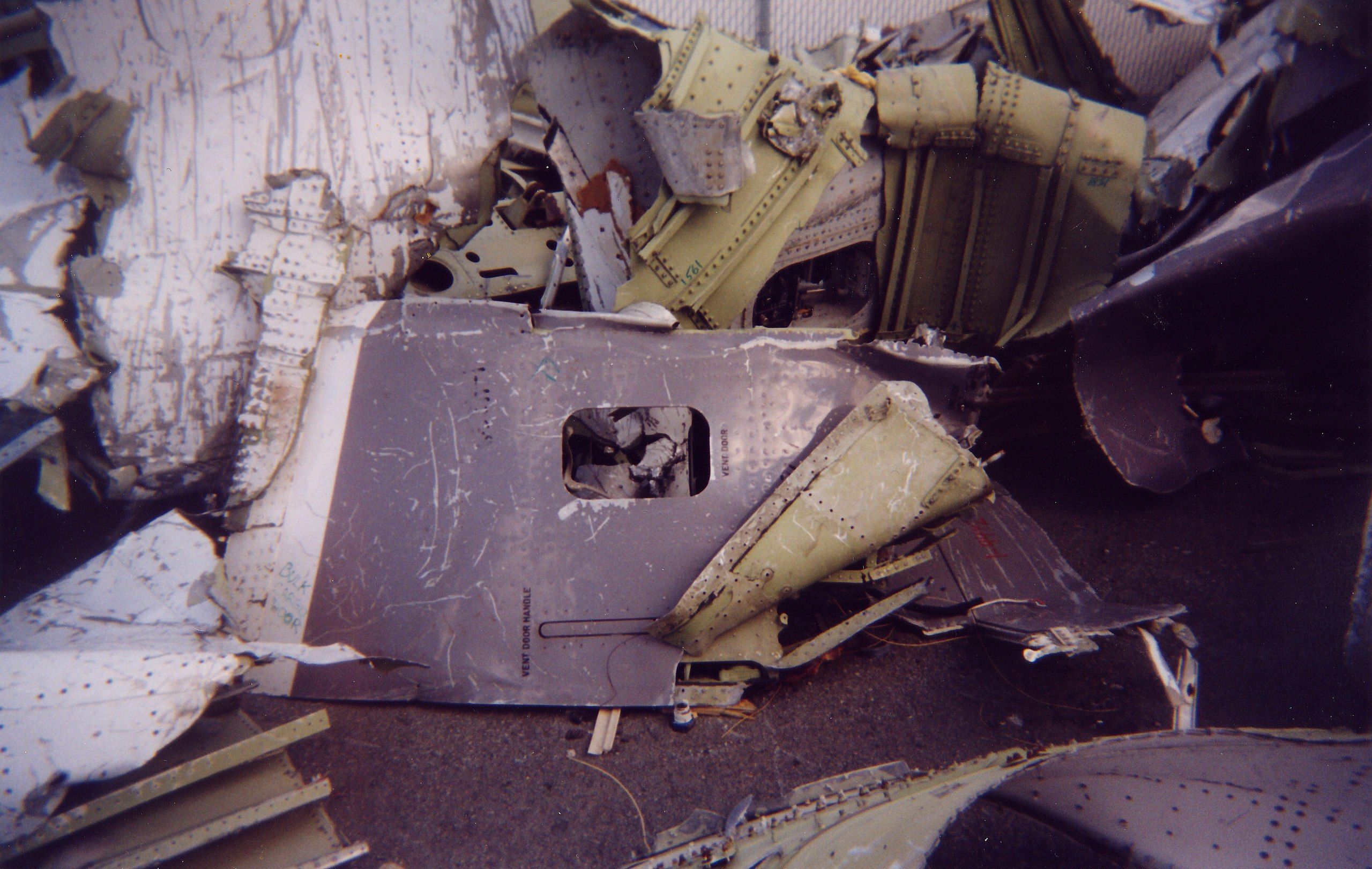

- The CVR and FDR black boxes were found by a submarine that detected the underwater beacon signals.

- On October 2, the Transport Safety Board started a heavy lift operation to retrieve the largest pieces of wreckage from the ocean floor.

- By October 21, 27% of the aircraft had been recovered. In the final phase, a ship dredged the remaining debris.

- By December 1999. 98% of the aircraft had been retrieved for the investigation.

The investigation was the largest and most expensive in Canadian history, costing $57 million Canadian dollars over a five year period.

Side notes

It is not known whether the cabin crew prepared the cabin for a ditching, but one licensed pilot flying as a passenger was found wearing a life vest. Swissair was in financial trouble in the 1990s and the new IFE system was brought in (a first of its kind) to attract more customers on their long-haul routes. It had been newly fitted on the MD-11. Onboard the aircraft were a Picasso painting, two kilograms of diamonds and 50 kilos of currency for a Swiss bank.

Cause of the accident

The Transportation Safety Board of Canada investigation identified eleven causes and contributing factors of the crash in its final report. The main cause was:

“Aircraft certification standards for material flammability were inadequate in that they allowed the use of materials that could be ignited and sustain or propagate fire. Consequently, flammable material propagated a fire that started above the ceiling on the right side of the cockpit near the cockpit rear wall. The fire spread and intensified rapidly to the extent that it degraded aircraft systems and the cockpit environment, and ultimately led to the loss of control of the aircraft.”

Contributing factors

After the crew cut power to the cabin systems, a reverse flow in the cockpit ventilation ducts increased the amount of smoke reaching the flight deck. By the time the crew became aware of the severity of the fire, it had become so extensive that it was impossible to control it.

The rapid spread of electrical power failures led to the breakdown of key avionics systems and the crew was soon unable to control the aircraft. The flight crew were forced to fly manually because they had no light by which to see their controls after the instrument lighting failed. The fuel-laden plane was above maximum landing weight, so the flight crew started dumping fuel. The pilots lost all control and the doomed plane flew into the ocean uncommanded.

Related

Air Canada’s Gimli Glider: A Cabin Crew Perspective

A true miracle of aviation.

As a result of the accident, extra fire-fighting training was devised for cabin crew and smoke detectors onboard were upgraded. Swissair was declared bankrupt in 2002. Two memorials were established by the Government of Nova Scotia, one close to Peggy’s Cove and one at Bayswater Beach.