Summary

- Pratt & Whitney Canada’s team designed the PT6 gas turbine engine for twin-engine aircraft.

- De Havilland Canada developed a twin-engine STOL plane, the Twin Otter, using the PT6A-20 engine.

- Ken Bullock, a British aviation engineer, contributed to the Twin Otter’s design and later worked on the Handley Page Jetstream.

In 1956, the president of Pratt & Whitney Canada, Ronald Riley, asked engineering manager Dick Guthrie to put together a team to design a small gas turbine engine. While the demand for the company’s Wasp radial engine was good, Riley’s goal was to make Pratt & Whitney Canada’s leading engine company by focusing on a small gas turbine engine.

Working with a modest amount of money, Guthrie put together a team of twelve engineers who, between them, had worked for the National Research Council in Ottawa, Orenda Engines, Bristol Aero Engines, and Blackburn Aircraft.

After completing the Pratt & Whitney JT12, the team began designing the PT6 for twin-engine aircraft. However, the project was nearly canceled due to delays, cost overruns, and a lack of orders. Using a Beechcraft Model 18, the test aircraft of the PT6A-6 was certified in December 1963.

In the early 1960s, de Havilland Canada sought a twin-powered plane to replace its single-engine, high-wing DHC-3 Otter STOL utility transport. The new twin-engine aircraft had to retain the DHC-3 Otter STOL qualities to appeal to bush plane operators.

When de Havilland Canada heard about the new 550 shaft horsepower Pratt & Whitney PT6A-20, the concept of building a twin-engine STOL plane became more feasible. Almost immediately, Bush plane operators warmed to the idea of a more robust and reliable turboprop, helping to convince de Havilland Canada that they were on to a winner.

Related

Home Sweet Home: Canada’s DHC-6 ‘Twin Otter’ Operators In 2024

Viking Air is now building the Twin Otter in British Columbia, Canada.

About Kenneth Bullock

Kenneth Bulock was born in South Kensington, just west of Central London, on June 19, 1932. Ken’s mother died when he was very young, and he went to live with his grandmother.

Ken was sent to live and be educated at Mote House, owned by a Quaker charity called the “Caldecott Community,” when he was six years old. He recalls vividly the build-up to WWII and seeing a Deutsche Luft Hansa Junkers Ju 52 trimotor with a Swastika emblem on the tail fin at Croydon Airport.

Because Mote House was located near Maidstone in Kent, halfway between Dover and London, Ken often witnessed dogfights between RAF and Luftwaffe fighter planes. In 1941, the Army commandeered Mote House, and the school relocated to Hyde House in Bere Regis, Dorset.

While attending high school, Ken’s interest in aviation grew further after cycling to a hill near RAF Tarrant Rushton and watching glider pilots train for the D-Day invasion. Following the war, the Caldecott Community relocated again, this time to Mersham Le Hatch in Kent, where Ken attended Ashford Grammer School.

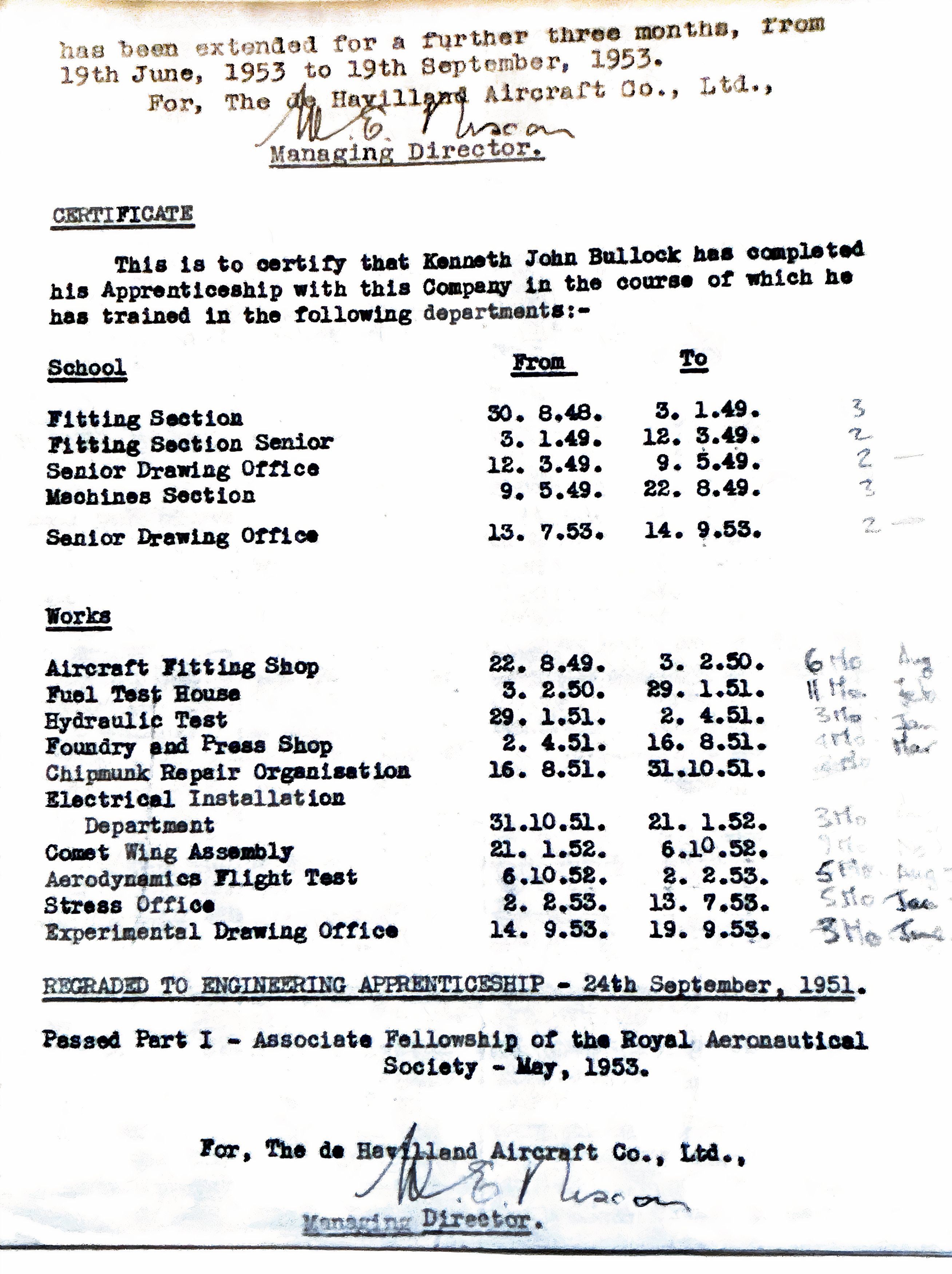

Photo: Ken Bullock

After leaving school, he began his apprenticeship at the de Havilland Aeronautical Technical School at Hatfield Aerodrome in Hertfordshire. During his apprenticeship, he was mainly involved with the de Havilland DH.106 Comet.

He remembered the somber mood in the factory after a prototype DH 110 (Sea Vixen) crashed during an aerial display at the 1952 Farnborough Airshow, killing two crew and 29 people in the crowd.

Making the move to Canada

After finishing his apprenticeship, Ken worked for de Havilland Design Draftsmen between 1953 and 1956. In the mid-1950s, the British aviation industry was consolidating, leaving many people wondering about their job security. Now married with a young family, Ken was offered a job in Canada by Avro Aircraft Limited Malton.

Image: Ken Bullock

The company heavily subsidized the move to Canada, and between 1956 and 1957, he was a designer on the Avro CF105 Arrow, a supersonic delta-wing fighter. Knowing that the project would likely be canceled in 1957, Ken went to work for de Havilland Canada, where he was involved in designing the DHC-4 Caribou and the DHC-5 Buffalo.

In 1960, Ken returned to the United Kingdom for ten months to help design the DH121 Trident, a plane that would later become the Hawker Siddeley HS-121 Trident. When Ken returned to Downsview, he was given the job of redesigning the single-engine DHC-3 Otter to become the twin-engine DHC-6 Twin Otter.

Designing the Twin Otter

Because of the costs involved, de Havilland Canada wanted a simple rework around the DHC-3 using its tubular structure and cockpit and adding a fairing over the nose. Ken’s job was to review this request based on the work he had already done on the Caribou and Buffalo.

Photo: Ken Bullock

Ken, however, had a different idea. It involved using the current cabin/cockpit bulkhead as the basis of a new structure designed specifically for the Twin Otter rather than a simple conversion. Ken convinced his boss, Fred Buller, that his idea was the best solution, and Buller agreed that a mock-up should be built to help persuade the people responsible for allocating the funds.

Ken’s new design had more oversize windows than the existing Otter, and he suggested showing the money people the old design first and then the one with larger windows later. Fred Buller said it would be better to show the new design first to show them what they would be missing out on if they did not go with the new concept.

Photo: Ken Bullock

The larger window was not the only thing Ken contributed to the de Havilland Canada DHC-6 Twin Otter, as his redesigned bulkhead made the cantilever structure for the nose wheel possible.

After the birth of his third child and his two older children’s readiness to go to secondary school, the family returned to England, and Ken worked again for de Havilland/Hawker Siddley at Hatfield. Ken later got a job with Handley Page as a Senior Designer on the Handley Page HP.137 Jetstream twin-turboprop airliner.

Taking a flight on the Twin Otter

In 1966, just as Ken was leaving Hawker Siddeley to start his new job with Handley Page, he met test pilot Bob Fowler for lunch. Fowler said that he and former RAF night fighter ace and the company chief test pilot, John Cunningham, were planning a test flight in the Twin Otter.

Ken asked if he and a colleague could come along, and Fowler said yes. Ken and his workmate traveled to Hatfield for the flight a week later.

During WWII, John Cunningham flew a Bristol Blenheim night fighter and was credited with 13 victories during the Blitz. After the war, Cunningham rejoined de Havilland as a test pilot, and on July 27, 1949, was the first person to pilot the de Havilland Comet jet airliner.

Once the Twin Otter was airborne, Cunningham took the controls and decided to stall the plane deliberately. Ken had never experienced anything like this and was suitably impressed. His colleague, however, was nearly scared to death.

Related

De Havilland Launches New & Improved Twin Otter With Orders For 45 Aircraft

The Canadian manufacturer is reviving production of its trusty Twin Otter with a fully updated model.

Of all the aircraft Ken was involved with during his working life, the de Havilland Canada DHC-6 Twin Otter is the one he is the most proud of. He hopes its production will continue for years to come.

Photo: Viking Air

On February 24, 2006, British Columbia-based Viking Air purchased the type certificates from Bombardier for the DHC-6 Twin Otter and currently sells the plane as the Viking Air DHC-6 Series 400.