Quick Links

Pilots use radios in every phase of flight. When tuned to the desired frequencies, radios can connect pilots to dispatchers, maintenance, company operations, air traffic controllers, and even medical doctors on the ground. One challenge of such a heavy reliance on radio communication is keeping all the frequencies in an ordered manner so that they can be found easily. This article will identify many of the lesser-known communications pathways that radios offer pilots and discuss how pilots are trained to find these frequencies.

HF radios

If you’ve read previous articles about flying to Hawaii from the US mainland or traversing the North Atlantic tracks, you might remember that pilots mainly rely on CPDLC and text formats to communicate with ATC and their company. However, high-frequency radios are the backup to these newer (and much quieter) forms of communication. HF radios have a very long range and work better over the ocean than VHF radios, though they aren’t nearly as clear. HF radio waves are transmitted high into the ionosphere before being reflected downward towards the Earth, whereas VHF radios rely on line-of-sight transmission of radio waves.

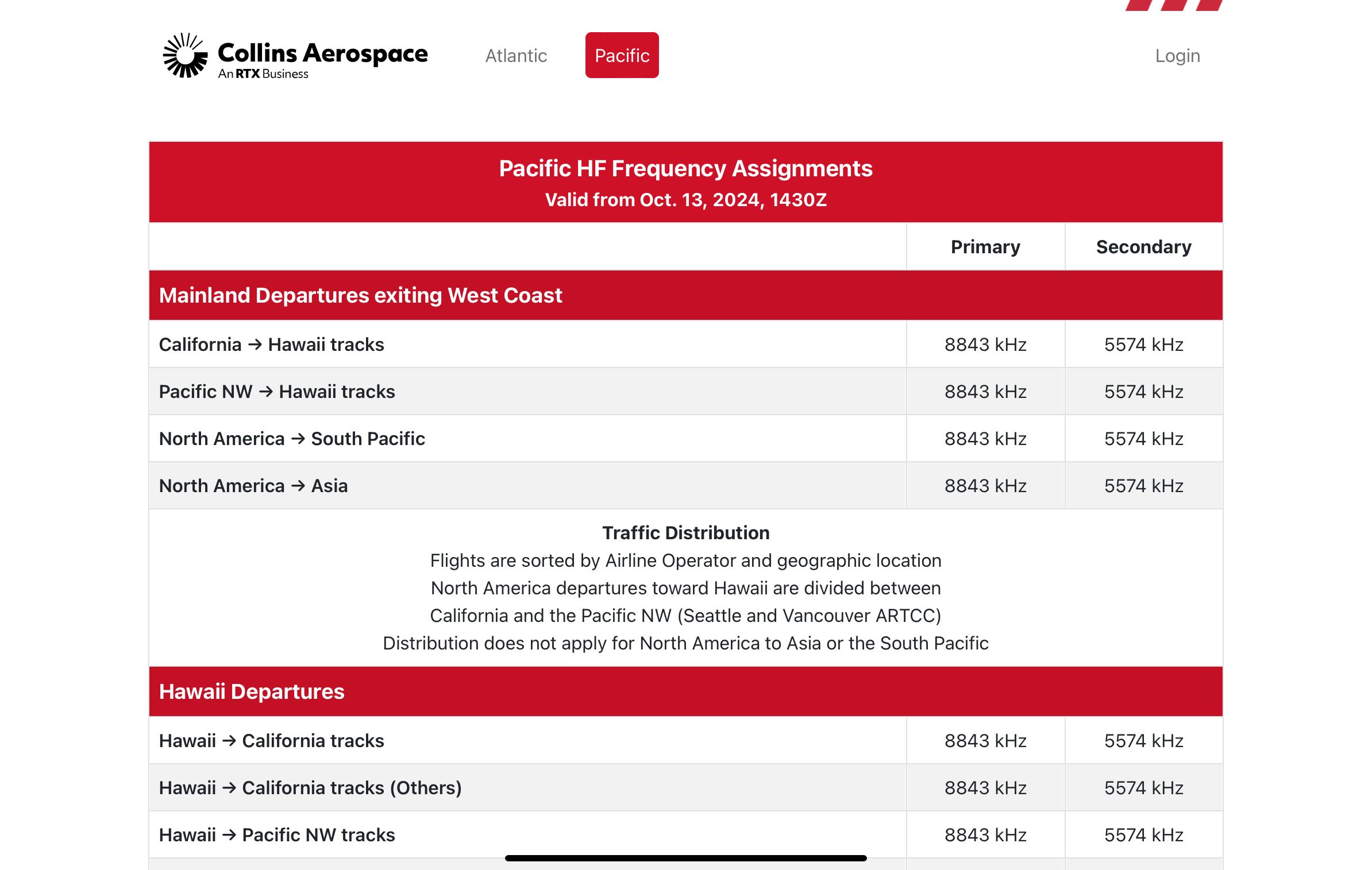

Since HF radio relies on the ionosphere and solar reflectivity, the frequencies that pilots and controllers use change depending on the season (due to the sun’s angle) and the time of day. Before setting off on an overwater flight, pilots check with their dispatcher and flight plan to obtain the HF radio frequencies that will be in use during their flight.

One place to find the proper frequencies for Hawaii flights is on a website kept up-to-date by Collins Aerospace. The table (see the image below) on the website lists the frequencies depending on the direction of flight and the origin airport. When pilots enter oceanic airspace, they use the frequencies listed to obtain a “SELCAL” check, which ensures their HF radios are working correctly. After this is done, it’s unlikely that they will use their HF radios again during the flight since most communications occur via CPDLC. However, HF is a tried and true backup.

Photo: Collins Aerospace

Medical providers

No one ever wants to see someone become so ill in flight that a doctor is needed. However, it happens many times every day, and pilots and cabin crew are trained to contact doctors on the ground to consult about the patient’s condition. The flight doctors have a vital role: they have to balance the operation’s interests against the patient’s criticality. The doctor usually has the most critical opinion regarding the decision to divert, though this discretion also belongs to the captain and the dispatcher.

Related

How Medical Emergencies On Flights Are Handled: 5 Things You Should Know

The AMAA, a physician’s conscience, and airline policies all dictate how medical emergencies are handled.

After gathering information about the patient’s health, pilots contact the medical provider that their airline contacts with via SATVOICE, VHF, or HF radio (if over the ocean). Perhaps the most challenging task in this situation is quickly finding the best frequency to establish the radio or phone patch with their company, which will, in turn, open the communication channel with the doctor.

Many airlines have a publication in their operations manual that contains these frequencies. Sometimes, this page is a map with divided sectors and corresponding frequencies. In other cases, some airlines might have an alphabetical table of airports or cities with the frequency next to it. Depending on where pilots are, they can select the frequency which will provide the best signal strength and clarity.

Two radios, minimum

Pilots use the second radio to establish comms with their company for medical, operational, and maintenance inquiries. Every airliner has at least two VHF radios, and many have three or more. During normal operations, pilots monitor “guard” frequency (121.500 MHz) to listen for aircraft in distress or controllers who might be trying to get in touch with them via alternate means. Pilots can quickly and easily change the frequency from 121.500 to whichever is needed to contact the airline. In the meantime, they stay in contact with the ATC sector they are in with the number one radio.

Ground operations

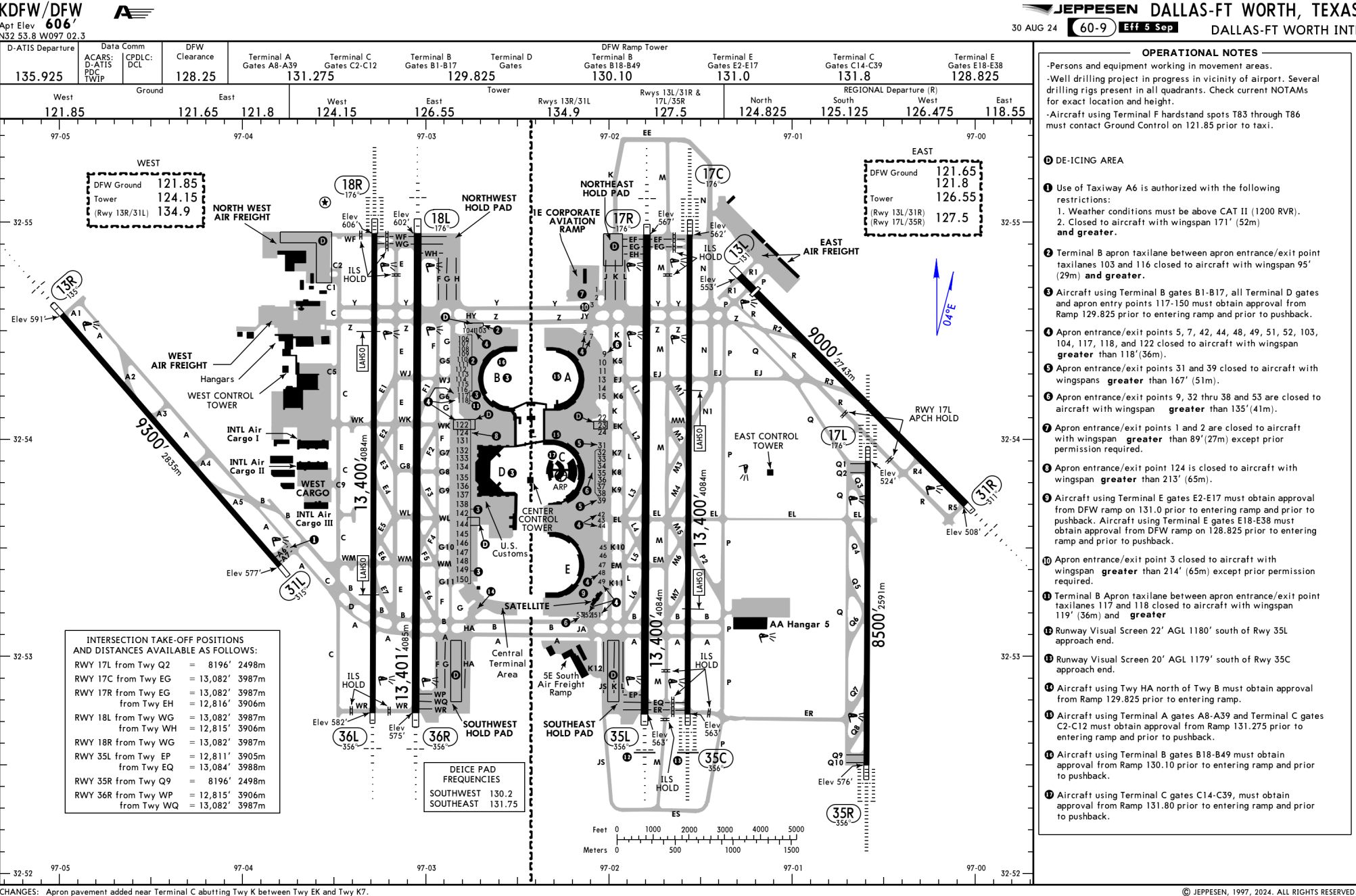

Every pilot, from the general aviation world to airline professionals, cares about the ATIS (weather info), ground, and tower frequencies for their airport. These frequencies are easy to find because they are listed at the top of the published airport diagram page. However, some airports are large enough to require multiple ground, tower, approach, and departure frequencies. When this is the case, all frequencies are listed with corresponding locations and additional instructions. An excellent example is Dallas/Fort Worth International, which has 19 listed ATC frequencies. See the top section of the image below.

Photo: Jeppesen

Another consideration for airline pilots is the frequency with which they contact their company operations at that particular airport. Operations is a lifeline for pilots because they help pilots handle everything from passenger issues, gate information, catering, and many other topics. This frequency is available to pilots on the “special notes” or “company pages” publication that the airline publishes specifically for each airport where they have a presence.

In addition to the all-important “ops” frequency, many larger airports with a significant airline presence have dedicated maintenance staff on call. Accordingly, a maintenance frequency is listed on the company pages when this is the case. When pilots call the maintenance frequency, they use their aircraft’s tail or “ship” number instead of the call sign used for the flight. Maintenance doesn’t care as much about the flight number as they do about the plane they will be working on.

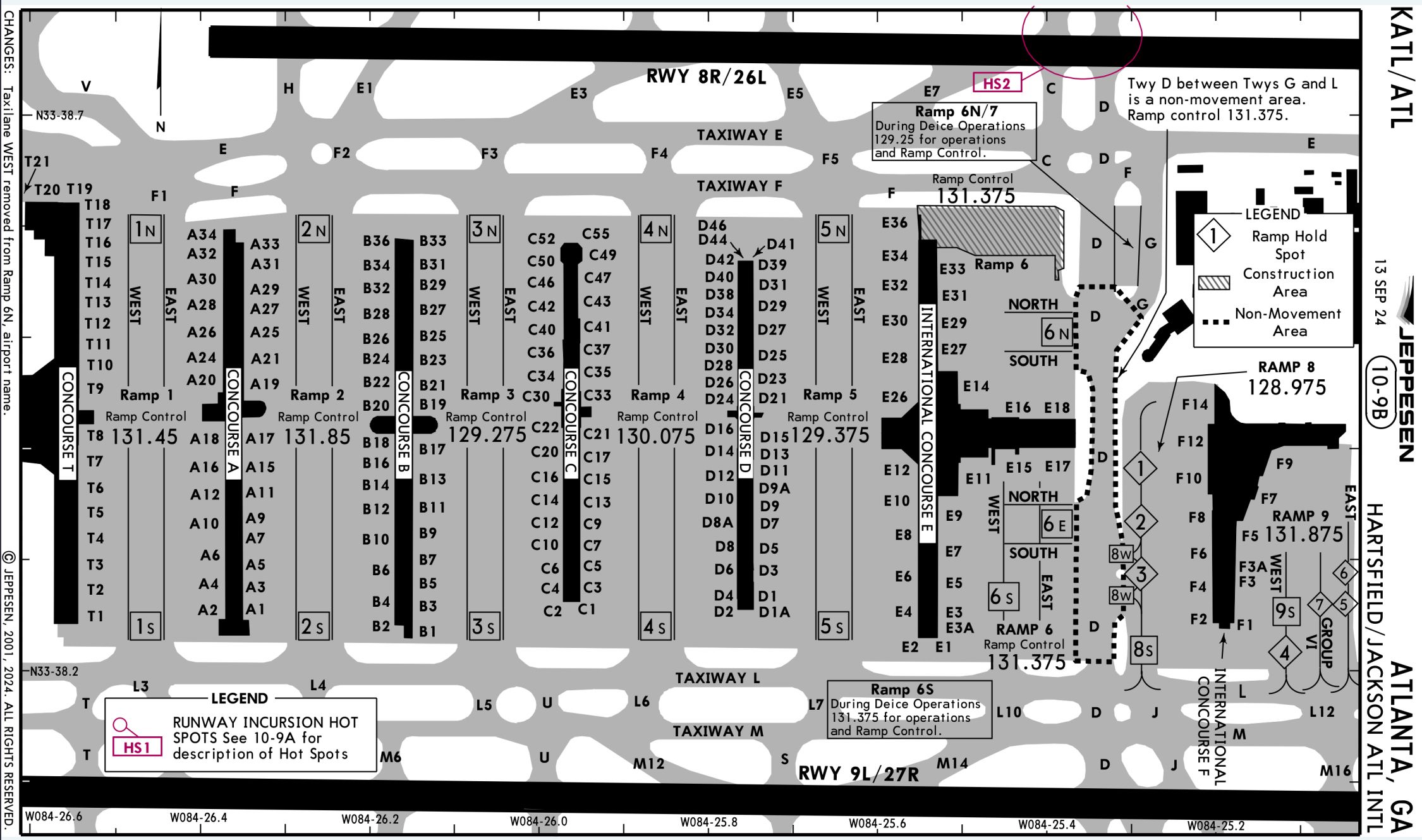

Another vital ground operational frequency not included on the airport diagram is the ramp area. The ramp, or apron, directly surrounds the gates where planes push back and start. Many large airports have ramp controllers (not the same as air traffic controllers) who manage the flow of pushbacks and arrivals on the busy ramp spaces. The best example of ramp frequencies is Atlanta’s Hartsfield-Jackson International diagram. Atlanta has nine ramps and eight dedicated frequencies for them. Check out the image below and see if you can locate all eight frequencies and who you will call depending on which gate you are at.

Photo: Jeppesen

Enroute ATC

Planes that are en route and over land are almost always in direct voice communication with air traffic controllers. Throughout a five-hour transcontinental flight from LA to New York, pilots will speak with about 20 controllers from at least six different ARTCC centers, not to mention the ramp, ground, tower, and TRACON controllers on both ends. Enroute center controllers instruct pilots to change frequencies every 10–20 minutes on this journey, and sometimes these handoffs are forgotten or mishandled. When this happens, pilots can find themselves wondering which frequency to tune to get in contact with a controller.

The easiest solution to this minor problem is to return to the previous frequency. Though the VHF frequencies used are subject to line-of-sight limitations, controllers and pilots can usually communicate after the pilots have flown beyond a controller’s sector. Therefore, the controller can see where the pilots are and assign them their new, proper frequency.

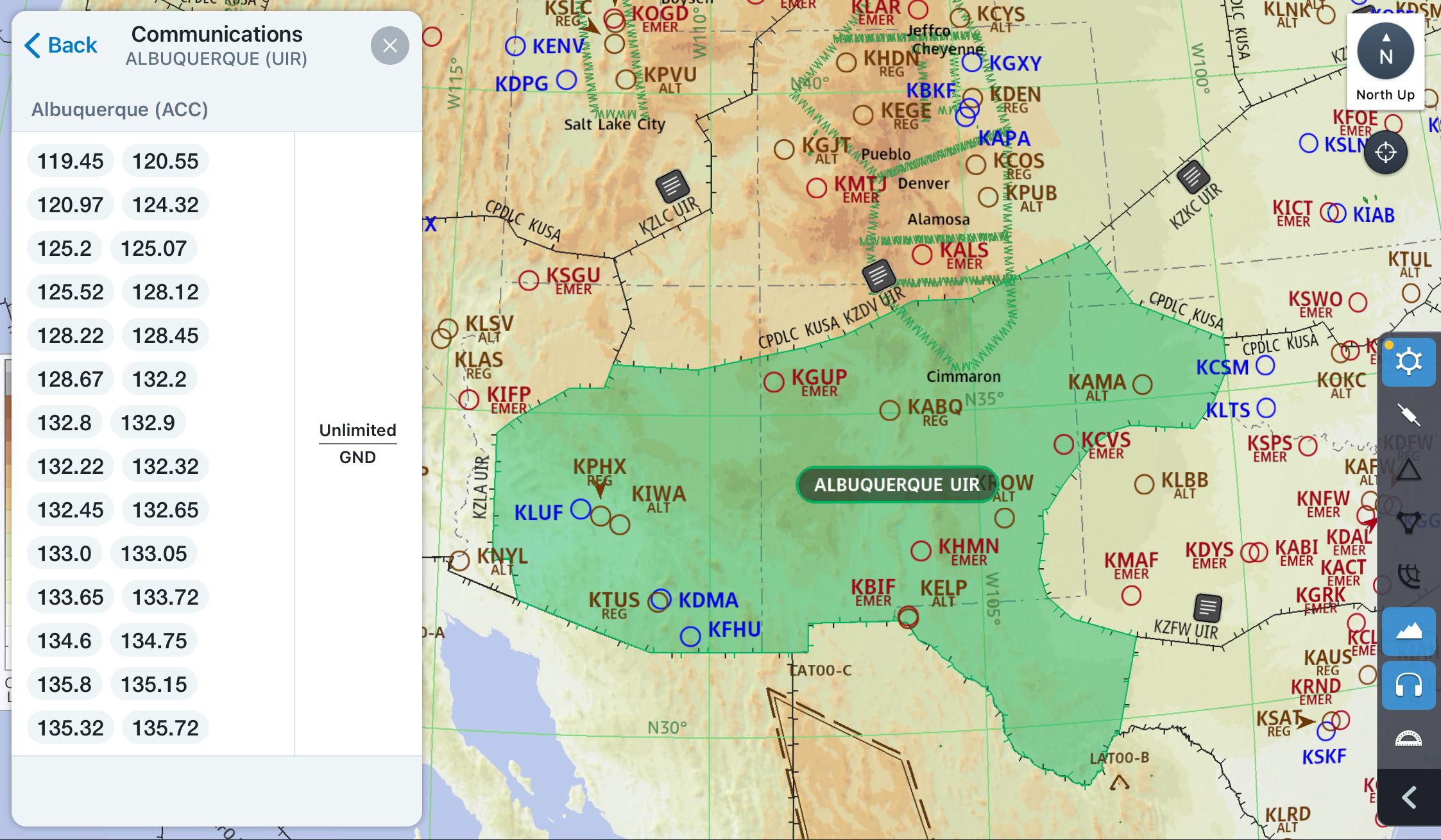

If the pilots cannot reach their last controller, smart maps on the pilot’s electronic flight bags display all the frequencies for ARTCC sectors. For example, the image below shows the boundaries and frequencies for Albuquerque Center in the western US. As another alternative, pilots could reference an airport diagram for an airport within their vicinity for an approach or departure frequency. Due to their proximity, the TRACON controller would be able to hear the pilots and help determine the proper frequency. Lastly, pilots could query ATC on guard (121.500) since controllers always listen to this frequency, just like pilots.

Photo: Jeppesen

Deicing

Some frequencies could be described as seasonal—such is the case with deicing radio communications. Pilots need direct communication with ground personnel when deicing or anti-icing is required. Deicing can be procedurally heavy due to the many items on the checklist needed to configure a plane before deicing, emphasizing the need for easy communication between the flight deck and the deicing crew.

Deicing frequencies can be found in a few places. The first place pilots can look is their company pages. During the process, large airports have a discrete, dedicated frequency that pilots use to talk to the “iceman” (the codename used for the lead deicing agent). The iceman needs to know if the engines and APU will be running and how the plane will be configured. The iceman also needs to inform the pilots when the deicing has commenced and when it is completed. Pilots use this information to calculate the all-important “hold over time,” or how long they have to takeoff until their anti-ice program needs to be repeated.

Related

A Pilot’s Guide To De-Icing

When and why airlines are required to deice prior to departure.

Sometimes, deicing doesn’t require any frequency. In this case, a ground crew member uses the headset plug-in on the nose of the plane to establish interphone communications with the flight deck. This is the same method that pushback tug drivers use to talk to the pilots. This is uncommon, and pilots usually speak to the driver of the deicing truck via VHF radio. The person in the bucket on the top of the truck who sprays the fluid is looped into the conversation by wearing a headset and monitoring the frequency.

Approach navigational aids

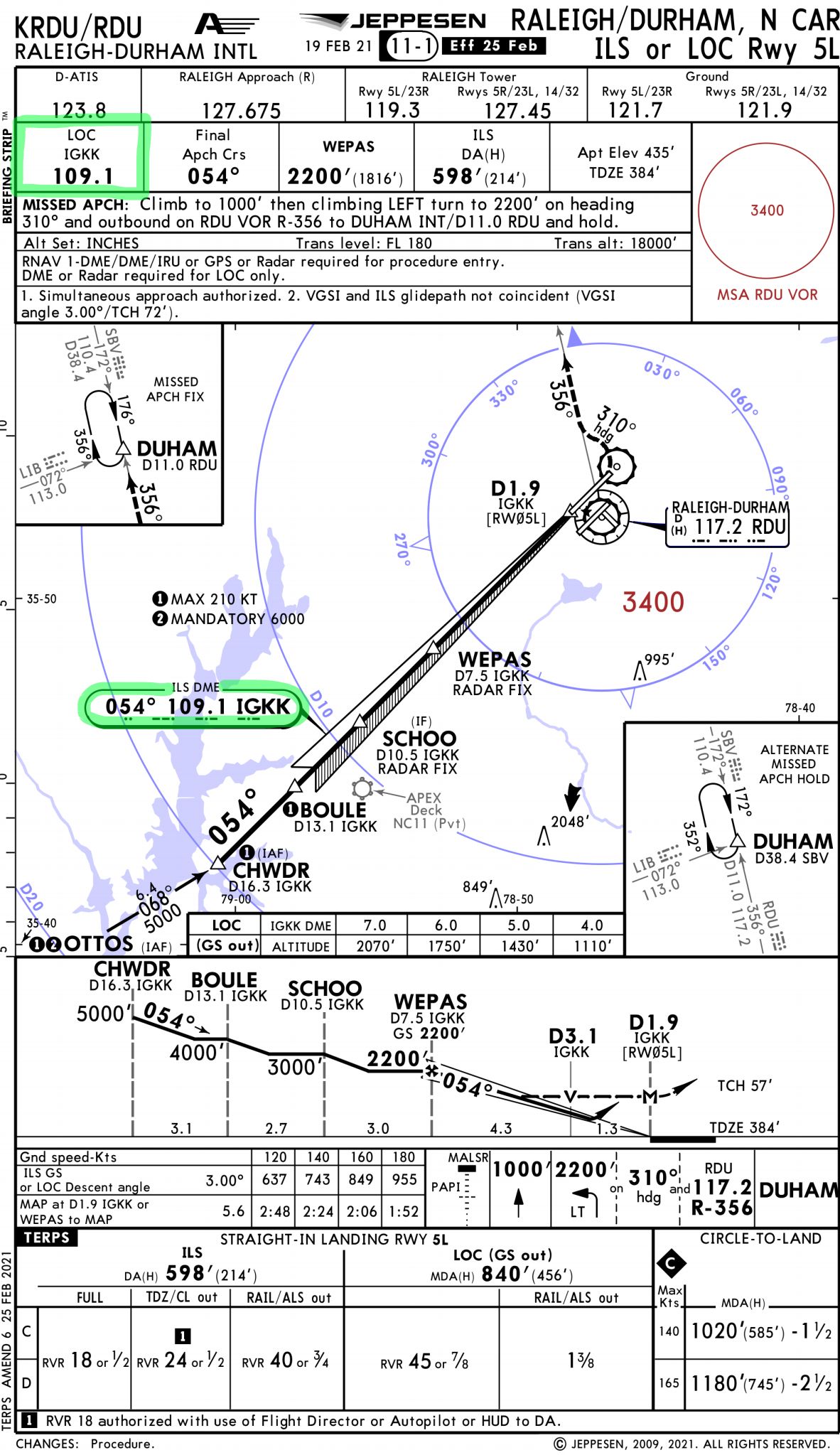

One final place that pilots look for frequencies is on approach charts. Pilots must ensure they have the correct VHF frequency tuned and identified for the runway they are meant to use, particularly when using ground-based equipment, like a localizer or VOR frequency. Improperly tuning a localizer frequency can result in confusion during the approach or even the plane capturing the localizer for a parallel runway.

Photo: Jeppesen

Approach plates (detailed depictions of an approach procedure) feature navigational aid frequency in multiple places. The frequency is listed in bold at the top of the chart and located on the “plan view” next to the depicted course in the illustration, a bit lower on the approach plate (highlighted in green in the image above). The point is to make this frequency obvious and accessible in a pinch so that pilots can reference it during their descent and approach checks.

Tried, tested, and true

Aviation and navigation depend heavily on VHF, HF, and UHF radios and their dedicated frequencies. It might come as a surprise to know how much radios are used for commercial aviation, especially given the amount of available telecommunications technology. On the contrary, it’s pretty difficult to imagine an aviation landscape that doesn’t involve a lot of radio telephony. When one stops to think about it, one of the most-used skills pilots employ is radio communications and operations. Radios are the most essential communication line for pilots to communicate with the outside world. Accordingly, knowing where to find frequencies quickly is a big part of the job.